Introduction

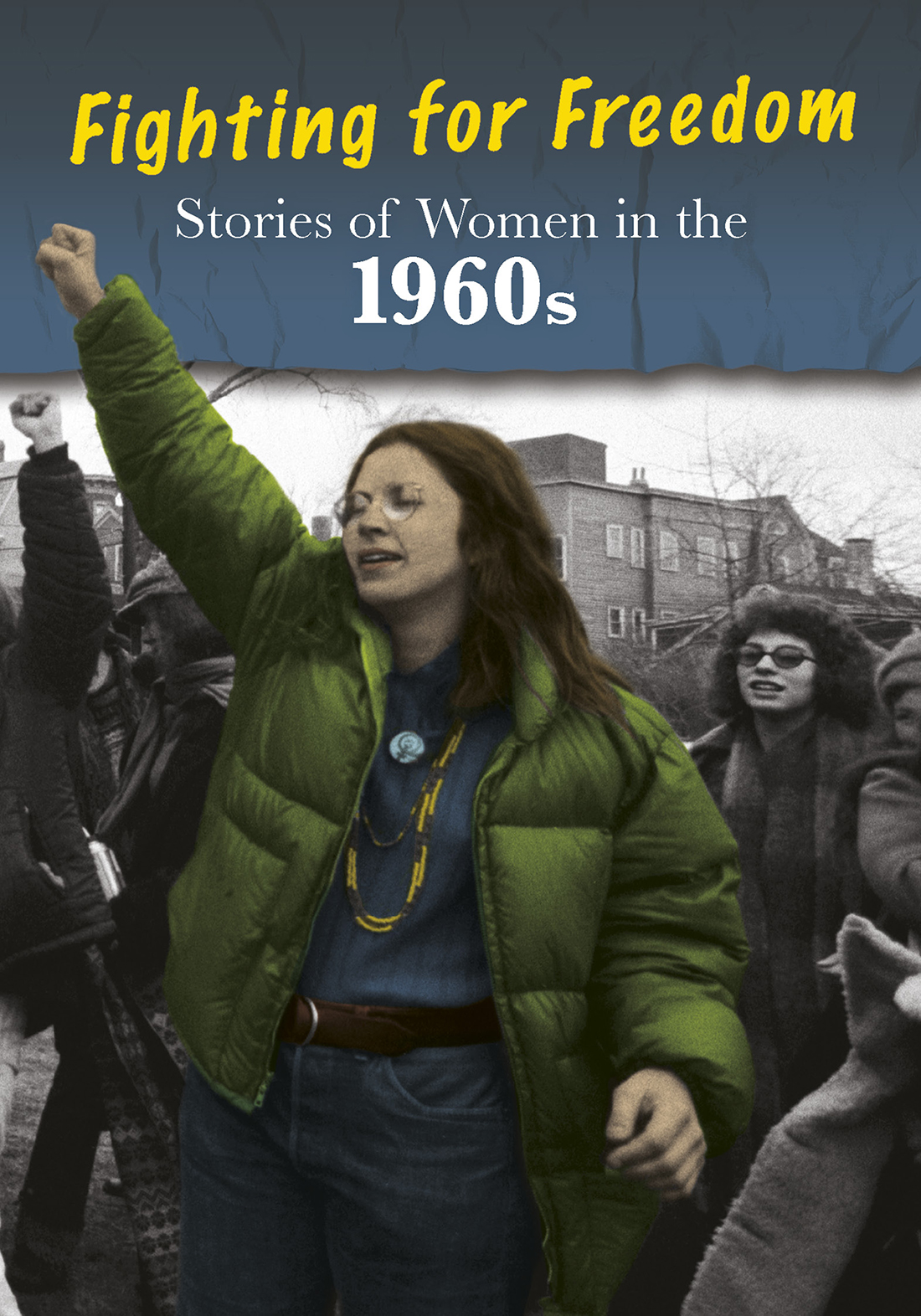

By 1960, American and British women felt like second-class citizens. Growing numbers were going to college, but they usually ended up in inferior jobs to men. They were paid less and found it hard to advance in their career. Women were frequently secretaries or teachers, but they rarely managed companies or became principals.

In the United States, African American women were treated even worse because of African Americans could not.

Frustrated with their situation, in the 1960s, American and British women began a movement for equal rights and freedom. This book tells the stories of four of those women.

Betty Friedan: Founder of the U.S.Womens Movement

In the years after World War II (19391945), as the U.S. economy boomed, many Americans moved to comfortable homes in the suburbs to raise their families. Advertisements, television, and movies quickly began to support an ideal of a perfect suburban life held together by the glue of a perfect housewife. For women, this caused some problems. In giving their total focus to homemaking duties and perfection, these women had little room for pursuing their own interests or careers.

A woman named Betty Friedan helped change the way Americans viewed the role of women. In 1963, she published an influential book called The Feminine Mystique.In this book, she wrote:

Each suburban wife struggles with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at nightshe was afraid to ask even of herself the silent questionIs this all?

Throughout the book, she argued that many women felt unfulfilled in this role of housewife and needed other outlets for their talents and energy. As a result of this book, more and more Americansand, eventually, people around the worldreexamined the role of women at home and in the workforce. Some people agreed with her, while others felt offended or challenged by her ideas. Yet, over time, her work changed the lives of millions of women.

Betty Goldstein (born Bettye, but she dropped the e from her name) was born in 1921 in Peoria, Illinois. It was one year after American women finally achieved the vote, following a long campaign by the womens movement. The eldest of three children, Betty had a younger sister, Amye, and a brother, Harry, Jr. As a child, Betty was not comfortable with who she was. She wore glasses, had poor coordination, and suffered from asthma.

Betty got along well with her father, Harry. But her relationship with her mother, Miriam, was difficult. Miriam was an intelligent, talented woman who had edited the womens section of the local newspaper. After she got married and had a family, however, she gave up her job, as was expected at the time.

Years later, Betty said:

When people, reporters, historians, [ask] why me, why did I start the womens movement, I cant point to any major episodes of sexual discrimination in my early life. But I was so aware of the crime, the shame that there was no use of my mothers ability and energy.

Looking back, Betty believed that much of the tension in her household was partly the result of her mother feeling frustrated and unfulfilled in her role as a housewife.

Betty was highly intelligent. After high school, she attended Smith College, where she graduated with a degree in psychology. However, when Betty was offered the chance to study for a PhD, she decided against it. She had noticed several female academics who were single with no children. Betty was scared that pursuing a career would leave her lonely and unhappy. In this way, Betty was feeling the tensions she would later explore in her work. She already firmly believed in the equality of women. But she also knew that she wanted to marryalthough she would not accept a husband who thought women belonged at home.

In 1944, Betty moved to Greenwich Village, in New York City, and took a job as an assistant news editor at Federated Press, a small newspaper agency. Two years later, she moved to UE News. That year, she met Carl Friedan, who ran a small theater company. Carl and Betty married the following year, and although they loved each other, their relationship was stormy.

Their first son, Daniel, was born in 1948. In those days, most women gave up work to have a family. But Betty returned to the office when Danny was less than a year old. She stayed at UE News until she became pregnant again and lost her job. At the time, it was normal to fire pregnant women if they didnt volunteer to leave.

After the birth of her second son, Jonathan, in 1952, Betty began a writing career, penning articles for womens magazines. It was easier to combine with raising children than an office job. Four years later, she gave birth to her daughter, Emily.

In the 1950s, there was little child care for small children, and women were still expected to do all the housework. Carl was a good father, spending plenty of time with the children, but Betty ran the home single-handedly while balancing this with her freelance writing.

The Friedans frequently moved, but wherever they lived, Betty was always busy organizing in the community. In Rockland County, New York, she invited academics to visit on the weekends to talk to the local schoolchildren about their subjects and help to broaden their minds. This gave her some fulfilment. Although she had a working life as well as a family, she was beginning to sense that many women who were purely housewives were not fulfilled in their role.

When she attended her Smith College 15-year class reunion, Betty had the perfect chance to test out her theory. She prepared a questionnaire for her classmates. She asked how their lives had changed since graduation and if they were happy. Most of these highly educated women were now housewives. In fact, it was extremely common at the time for women to marry straight out of college and have children. There was even a debate in the media about whether higher education was wasted on women. Betty decided to write a book based on her findings. It took her five years to write, and The Feminine Mystique was published in 1963.

By this time, the situation for women was changing. The movement for was growing, and women were heavily involved in this. Increasing numbers of women were going to work. One-third of women had jobs, and one-third of married women were working. Yet many educated women were working in jobs that did not use their full potential. They were asking themselves, Is this all? Within society, people were debatingshould women only be housewives?

In The Feminine Mystique, Betty explained how women were told that their main function in life was to be a wife and mother. If they failed to adjust to this role, they would lose their femininity and not be seen as proper womena terrible fate.

With her background in psychology, Betty drew on the theory of psychologist Abraham Maslow. He found that once people had met their basic needs for food, shelter, and clothing, they needed some kind of purpose in life to achieve their potential. Betty showed that housewives were being denied their chance for human growth. They felt belittledrestricted to the role of homemaker caring for their husband and family, with no independent interests.Writing about this problem, she said: