Introduction

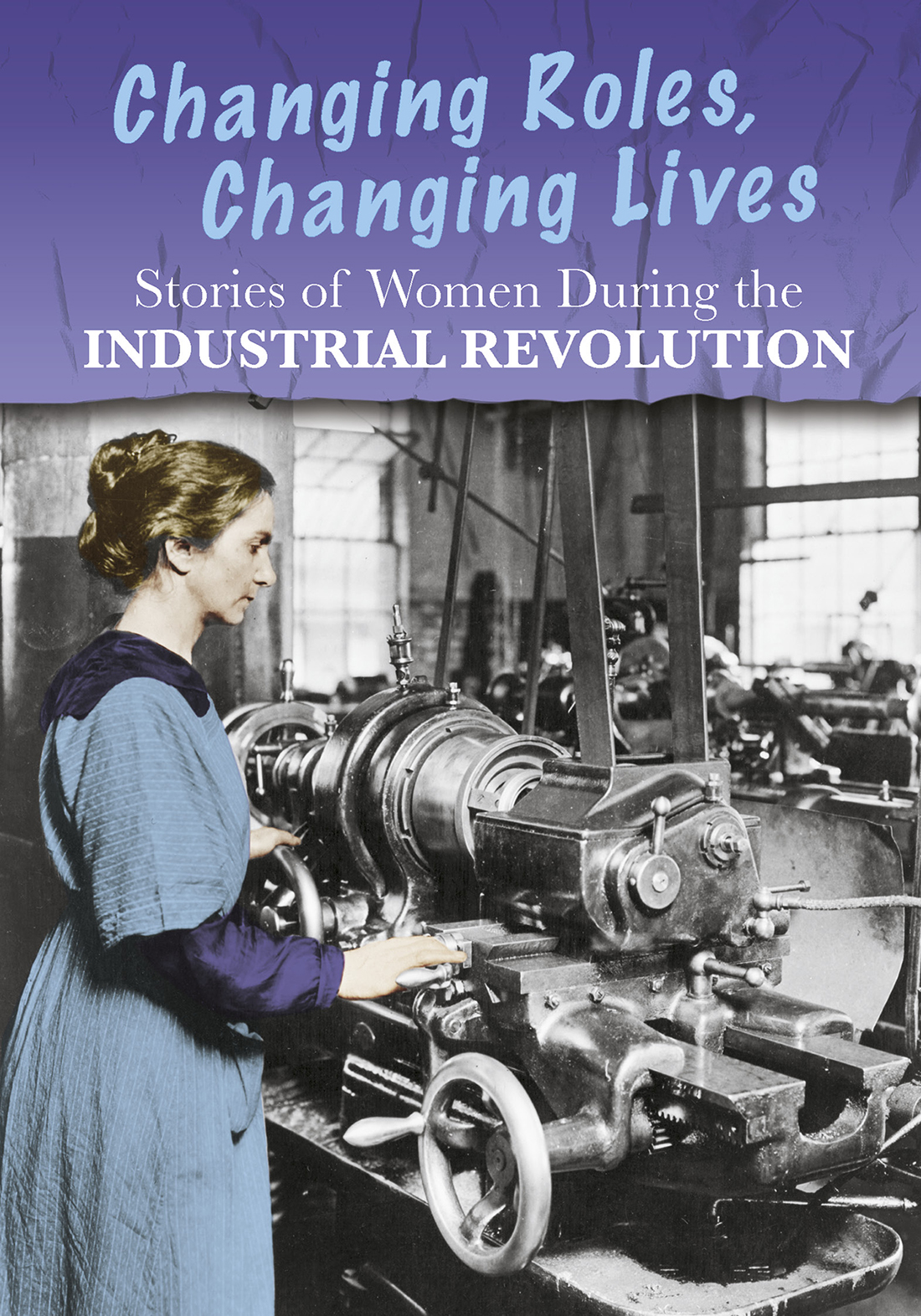

In the early 18th century in the United States and United Kingdom, most people lived in the countryside, where they worked as farmers or made goods using simple machines.

But from the mid-18th century, new machines powered by steam and coal began to produce goods on a massive scale. This was known as the Industrial Revolution.

People were hired to operate the machines in large factories, while others mined for coal. These people were badly paid and dealt with harsh working conditions. Life was particularly hard for working women, who received lower wages and fewer rights than men.

Some women, however, would not stand for the poor treatment of themselves or others. They dedicated their lives to helping those in need and supporting the rights of workers. Four such women were Elizabeth Fry, Florence Nightingale, Sarah G. Bagley, and Mother Jones.

Elizabeth Fry: Angel of the Prisons

Elizabeth Fry was a prison reformer who devoted herself to helping the female inmates of English jails.

She was born during the Industrial Revolution, a period rife with poverty and crime. The prison system was very harsh at this time. People were jailed or sentenced to death for minor crimes such as stealing or forgery. But despite these extreme sentences, many people thought prisoners should be locked away and forgotten. English prisons were overcrowded, filthy places that were full of disease and misery.

While many prisoners lost hope, Elizabeth Fry was determined to make their lives more bearable. Known as the Angel of the Prisons, Elizabeth believed that prisoners should be treated with compassion and kindness. Through her reforming work, Elizabeth changed the public view of prisons and improved conditions for those locked inside them.

Elizabeth Gurney was born into a wealthy Earlham Hall, where they often held dinners, concerts, and balls for friends. Elizabeth wore fine clothes, ate the best foods, and had enormous private grounds to enjoy.

However, she was a nervous and sickly child. Elizabeth was scared of the dark and could not sleep without a candle by her bed. The sea terrified her and she had nightmares about drowning. Even a glance from a stranger could make Elizabeth burst into tears. But despite her nervousness and health issues, Elizabeth was a kind, honest, and considerate person. She went out of her way to help those less fortunate than herself.

In 18th- and 19th-century England, most people were less fortunate than the Gurney family. The Industrial Revolution had made some people very wealthy and many people very poor. Whole families often left the countryside to find work in city factories. Here, workers toiled for up to 14 hours a day in dangerous conditions for little pay.

As a result of the high level of poverty in the cities, many people turned to crime. The rising cost of bread in the late 18th century caused riots in many cities, including Norwich. But Elizabeth was kept away from these troubles in Earlham Hall.

However, Elizabeth would be unable to ignore the . While Elizabeths time in London included opera visits and society dinners, she couldnt help wondering about those suffering in the slums. She felt she could do more with her life than just socializing.

Then, one day, Elizabeth went to hear a speech by an American Quaker named William Savery. The talk had a profound effect on Elizabeth. She decided to devote herself to helping others. Elizabeth wrote a statement in her journal about how she would live her life from that point on:

First. Never lose any time.

Second. Never err the least in truth.

Third. Never say an ill thing of a person.

Fourth. Never be irritable or unkind to anybody.

Fifth. Never indulge myself in luxuries that are not necessary.

Sixth. Do all things with consideration.

When Elizabeth returned to Earlham Hall, she began helping the poorer children in the area. She often bought them new clothes and organized classes for them in one of the mansions unused rooms. There was no public education system in the 18th century, and many children could not read or write. Boys of wealthy families often attended private schools, but it was unusual for girls to be educated. However, Elizabeth and her siblings had been taught by private tutors.

Schools for poor children were not established until 1811. Instead of school, poor children often worked alongside their parents in factories or coal mines, sometimes becoming chimney sweeps. The number of children Elizabeth educated in her makeshift classroom rose every year. By 1800, there were 86 of them, called Betsys imps by her family.

In the 19th century, daughters from wealthy families were expected to marry. So, in 1800, Elizabeth married a banker named Joseph Fry and moved to London to begin a new life.

Beyond the problem of slums were dirty and dangerous. Although she lived in a large mansion with many servants, Elizabeth often visited the slums to help the poor. She handed out food and clothes and even sent her own doctor to tend to the sick.

Elizabeth would give birth to 12 children of her own, but she always found time to help those in need. She rose at 4 a.m. to fit in all her days activities, which would soon include the work that made her famous. This began in 1813, when her friend Stephen Grellet told her about the terrible conditions he had witnessed in Londons Newgate Prison.

Stephen was a French aristocrat who was trying to reform Englands jails. At that time, all prisoners were locked up together, regardless of whether they were murderers sentenced to death or accused people awaiting trial. Inside the prisons, hundreds of inmates were crammed into tiny cells. There was usually no bedding or heating and often just a bucket for a toilet. When new prisoners arrived, the guards demanded a garnish from them. This meant handing over money or, if the prisoner had none, clothes to the guards. Prisons were privately run in those days, and demanding a garnish was how the guards made money. For those without money, life in prison could be very hard. These inmates were often fed only with soup made from water and a piece of bread. Many soon became sick from hunger, cold, or disease.

Newgate Prison had a particularly gruesome reputation. Here, condemned prisoners were executed by hanging in front of a crowd. Before the executions, people could pay to watch prisoners sitting in their cells next to their own coffins. Sometimes the condemned prisoner was a woman.

Stephen Grellet told Elizabeth he had been shocked by conditions for female inmates inside Newgate Prison. Many of the women were sick or starving, and all were cruelly treated by the male guards. Worse still was the sight of many newborn babies, most of whom were cold and naked. When Elizabeth heard Stephens story, she immediately decided to try to help the prisoners. Armed with blankets and clothes and accompanied by her friend, Anna Buxton, Elizabeth made her way to Newgate Prison.