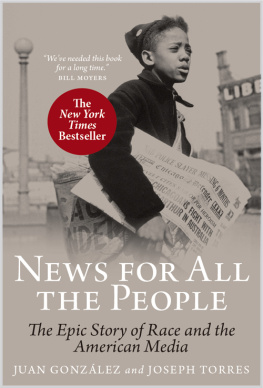

News for All the People

News for All the People

The Epic Story of Race and

the American Media

Juan Gonzlez and Joseph Torres

First published by Verso 2011

Juan Gonzlez and Joseph Torres 2011

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

eISBN: 978-1-84467-942-3

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Bembo by MJ Gavan, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Vail

For

Gabriela Gonzlez and Charis Torres

Contents

Introduction

The ways in which information passes through a society are the key to that societys culture and are inseparable from its understanding of how to preserve itself and its internal group relationships. It is the silences that control a society and keep it stable much more than the conscious noise it generates.

Anthony Smith, The Geopolitics of Information, 1980

In no place on earth has the daily production of news formed such an integral part of a peoples image of themselvesof a national narrativeas in the United States. From the earliest decades of the Republic, Americans consumed more newspapers per capita than any people on earth. Today, we are literally drowning in news and information; we have 1,400 daily newspapers, 1,700 full-power television stations, 12,000 radio stations, 17,000 magazines, and hundreds of channels to choose from on our cable systems. We have news at five, at six, at ten and at eleven oclock. We have a raft of twenty-four-hour cable news, sports and business networks, and hundreds of thousands of Internet news sitesfrom the Drudge Report, to the Huffington Post, to an endless stream of YouTube videos, all available at any hour of the day or night.

Access to instant news has become so indispensable to modern society that major media companies now wield unprecedented influence over public thought. The media amplify those events they wish to while exiling others to the shadows; they fashion political and popular heroes one day only to tear them down the next; they interpret the meaning of the most earthshaking or insignificant incident before our morning coffee or commute back home.

Despite this incessant chatter, many Americans remain remarkably misinformed about the world around us, while the professional journalists who produce our news routinely engender fear and loathing from the mightiest politician or celebrity, as well as from the lowliest citizen. The believability of our nations news organizations has plummeted sharply in recent decades. A 2005 survey by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press

In the pages that follow we sketch the origin and spread of the system of news in the United States, retracing how the media came to exercise such enormous sway over public life. It is a fascinating and complex story, one that has been told in great detail many times before, but our account diverges from previous efforts in two basic ways. First, we offer an overall theory of why the American news media developed the way they did. That theory centers on the key political choices our leaders in Washington made about the role of the press in a democracy. We show how federal lawmakers and the courts repeatedly responded to technological breakthroughs in mass communications by rewriting the rules governing the media industry. And while those revisions were usually done at the behest of powerful corporate interests, the government was forced on several occasions to adopt important reforms that made the press more democratic and accountable to ordinary citizens, usually in an effort to placate incipient social movements or to quell civil strife, especially during times of war. At each new stage of our media systems evolution, however, furious debate has erupted over the same question: Are the information needs of a democracy best served by a centralized or decentralized system of news? The resolution of that key question, we conclude, is paramount for defending a free and diverse press.

Second, we focus on how newspapers, radio, and television depicted a fundamental fault-line of US societythat of race and ethnicity. You will find gathered in one place for the first time the details of a startling number of major news events in which press organizations consciously misled the public and inflamed racial bias. In compiling these examples, our aim was not merely to dredge up embarrassing media failures from the distant past or to indulge in some abstract content analysis of old news. Rather, we have utilized these various examples to chronicle the key historical battles over racial discrimination that took place inside the US media. In addition, we document how advances in communications technology affected the medias depiction of race, and we recount the roles played by scores of individual journalists and media executivesthe famous and the obscure, the heroes and the villains, white and non-whitein the epic struggle to supply the American people with our daily news.

The News Media and Racial Bias

It is our contention that newspapers, radio, and television played a pivotal role in perpetuating racist views among the general population. They did so by routinely portraying non-white minorities as threats to white society and by reinforcing racial ignorance, group hatred, and discriminatory government policies. The news media thus assumed primary authorship of a deeply flawed national narrative: the creation myth of heroic European settlers battling an array of backward and violent non-white peoples to forge the worlds greatest democratic republic. This first draft of Americas racial history was not restricted to a particular geographical region or time periodto the preCivil War South, for example, or the western frontier during the Indian Wars; nor was it merely the product of the virulent prejudice of a few influential media barons or opinion writers or of a specific chain of newspapers or television stations. Rather, it has persisted as a constant theme of American news reporting from the days of Publick Occurrences, the first colonial newspaper, to the age of the Internet.

Stereotypes, of course, infuse the daily thinking of all human beings. Legendary newspaperman Walter Lippmann regarded them as essential tools for individuals to make sense of the complex world around us. Examining the origin and use of stereotypes in the media, Lippmann wrote in 1922:

Of any public event that has wide effects we see at best only a phase and an aspect Inevitably our opinions cover bigger space, a longer reach of time, a greater number of things, than we can directly observe. They have, therefore, to be pieced together out of what others have reported and what we imagine.

It is the job of the modern journalist to witness events in the wider world and then convey those events and their meaning to the rest of us as quickly as possible. But such reports are fraught with weaknesses inherent to each reporters own perception of realitythe subjectivity that so often springs from upbringing, education, class, race, religion and gender. The less the journalist knows about the event or the subject at hand, the more likely he or she is to produce a crude or blurred representation of it. Those reports are then further filtered by editors and publishers, who get to decide which portions of the reporters dispatch are newsworthy and will survive, and which will disappear in the editing process. Lippmann warned of the substantial distortions that were inherent to such a process:

Next page