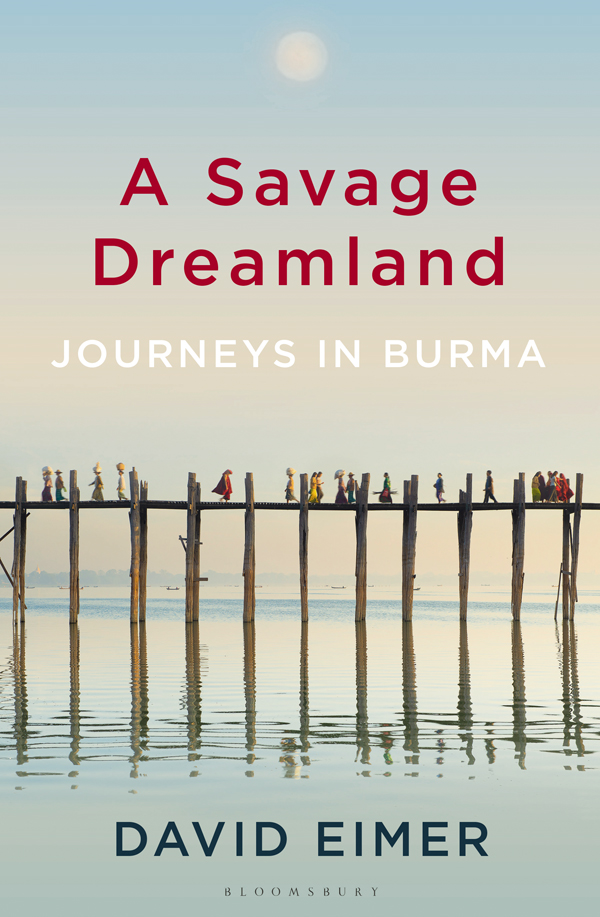

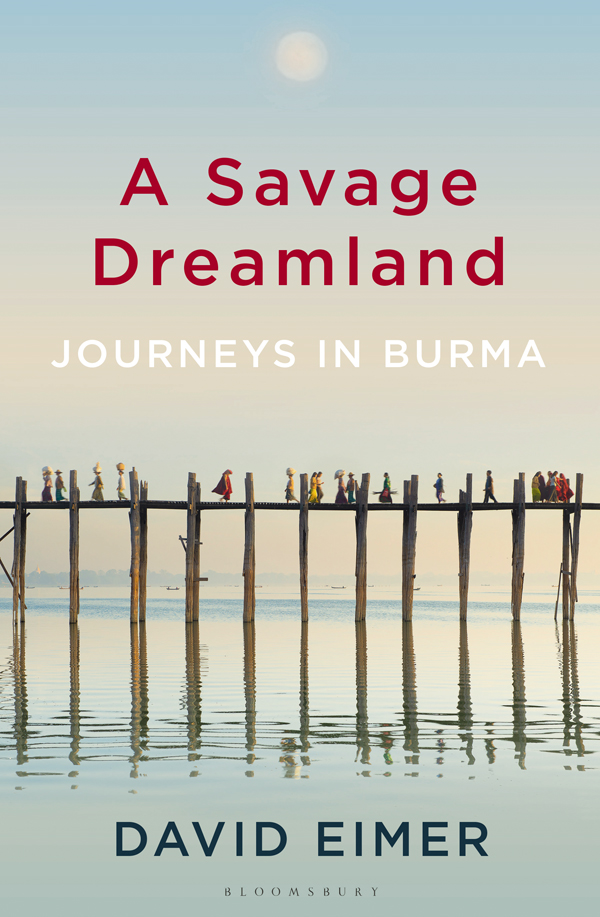

A SAVAGE DREAMLAND

Also available by David Eimer

The Emperor Far Away

Travels at the Edge of China

A revelatory and groundbreaking insight into the divisions within modern-day China

Far from the glittering cities of Beijing and Shanghai, Chinas borderlands are populated by around one hundred million people who are not Han Chinese. For many of these restive minorities, the old Chinese adage the mountains are high and the Emperor far away, meaning Beijings grip on power is tenuous and its influence unwelcome, continues to resonate. Travelling through Chinas most distant and unknown reaches, David Eimer explores the increasingly tense relationship between the Han Chinese and the ethnic minorities. Deconstructing the myths represented by Beijing, Eimer reveals a shocking and fascinating picture of a China that is more of an empire than a country.

A fascinating picture of a part of the country rarely examined

Daily Telegraph

This absorbing book is a tantalizing introduction to Chinas diversity and the ethnic and political dynamics at the extremes of its empire

Publishers Weekly

https://www.bloomsbury.com/author/david-eimer/

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/the-emperor-far-away-9781408864289/

BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2019

This electronic edition published 2019

Copyright David Eimer, 2019

Illustration copyright Martin Lubikowski, ML Design 2019

Extract from Shooting an Elephant from Narrative Essays by George Orwell published by Harvill Secker. Reproduced by permission of The Random House Group Ltd. 2009

David Eimer has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work

For legal purposes the constitute an extension of this copyright page

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for

ISBN: HB: 978-1-4088-8387-7; TPB: 978-1-4088-8388-4; eBook: 978-1-4088-8386-0

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters

Contents

Burma as represented on a modern political map is not a geographical or historical entity; it is a creation of the armed diplomacy and administrative convenience of late nineteenth-century British Imperialism.

Edmund R. Leach, The Political Future of Burma (1963)

Modern Burma is only dead Burma reincarnate.

C. M. Enriquez, A Burmese Enchantment (1916)

BURMA 2010

I came to Burma in search of the road less travelled. In early 2010, this was a mysterious nation: little-visited, barely mentioned, hardly known. A paranoid military dictatorship had ruled for almost fifty years and Burma had become the monster in the Southeast Asian attic, the unhinged relative locked in a top-floor room. While its neighbours hosted an ever-increasing number of tourists, the generals sought to isolate the country from outside influences and regarded foreigners with intense suspicion.

Three years before, in 2007, I had attempted to reach Yangon, Burmas largest city and the former capital, to cover the so-called Saffron Revolution, the latest popular uprising against army rule. Along with many other reporters, my visa application was refused. The closest I came to Burma was standing on the banks of the Moei River in the Thai border town of Mae Sot, waiting for the expected flood of refugees to wade across from the other side. But the exodus never happened.

When I applied again for a visa in Bangkok in January 2010, with a new passport untainted by any evidence that I was a journalist, it was still more in hope than expectation. Returning to the Burmese embassy the next day, my surprise on finding I had been granted twenty-eight days to visit was rather too visible. I boarded a plane for Yangon the next morning, just in case the officials changed their minds.

After the hustle of Bangkoks Suvarnabhumi Airport a giant, crowded shopping mall with runways Yangons international terminal could have been a provincial bus station on a slow day. There were no queues at passport control. A sole luggage belt revolved. Stepping outside, there was a sudden blast of heat, a cloud-free, azure sky and a bright sun that made me squint. I climbed into a taxi, its windows open in lieu of air conditioning, and asked the driver to take me to downtown.

We set off along a half-empty road overseen by palm and pipal trees, shaded in different hues of green. Their spreading leaves and branches partially masked the wooden houses topped with corrugated iron roofs and undistinguished concrete buildings behind them. Chinese-made trucks wheezed by belching black smoke, their exhausts mimicking the chimneys of the factories they had emerged from. There were few privately owned cars. Most, like my taxi, were falling apart in slow motion, their drivers unable to afford or find spare parts.

Walking along the broken-down pavements, or waiting for overloaded buses and pickup trucks, whose teenage conductors hung out of the doors and off the backs of their vehicles shouting out their destinations, were the locals. Almost everyone wore the sarong-like, traditional Burmese dress: sober-coloured longyi for men, brightly patterned htamein for the women. Only the Buddhist monks in their crimson robes stood out from the uniformity of the crowd.

What I was seeing could have been a street scene from the Yangon of twenty or thirty years before. Burma was in stasis; a country marooned under the junta that had snatched power in 1962. There were other reminders of the lack of progress, too. My mobile phone was in my pocket, its screen dark. There was no international network coverage in Burma. I discovered soon that the internet was a barely available, mostly non-functioning new invention as well.

But the shock of the old was alleviated by the faces I saw as we drove south. When my taxi stopped at the few traffic lights, people looked across at me from their crowded buses and some offered a shy smile, one that widened into a beguiling beam when I reciprocated. They made me feel like I was being welcomed to Burma, and that is the greeting every traveller hopes for.

A Chinese-owned hotel on the western edge of downtown was my first base. Yangon slopes gently downhill towards its eponymous river from its highest point, the hill where the Shwedagon Pagoda, Burmas most holy religious monument, sits. By leaning out of the window of my room and twisting my neck to the left, I could see down Wadan Street as it ran for three blocks to the Strand, the riverfront road, and the citys docks.

Next page