Aung San Suu Kyi

LETTERS FROM BURMA

Illustrated by Heinn Htet

Introduction by Fergal Keane

PENGUIN BOOKS

LETTERS FROM BURMA

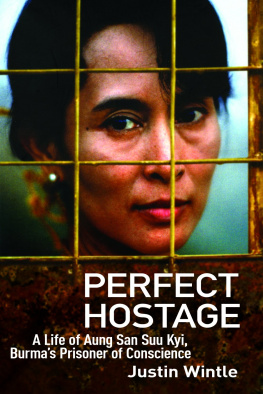

Aung San Suu Kyi is the leader of the struggle for human rights and democracy in Burma. Born in 1945 as the daughter of Burmas national hero Aung San, she was two years old when he was assassinated, just before Burma gained the independence to which he had dedicated his life. After receiving her education in Rangoon, Delhi and at Oxford University, Aung San Suu Kyi then worked at the United Nations in New York and Bhutan. For most of the following twenty years she was occupied raising a family in England (her husband is British), before returning to Burma in 1988 to care for her dying mother. Her return coincided with the outbreak of a spontaneous revolt against twenty-six years of political repression and economic decline. Aung San Suu Kyi (Suu to her friends and family) quickly emerged as the most effective and articulate leader of the movement, and the party she founded went on to win a colossal electoral victory in May 1990. In July 1989 she was put under house arrest and the military junta that now rules Burma refused for six years either to free her or to transfer power to a civilian government as it had promised. Upon her release in July 1995 she immediately resumed the struggle for political freedom in her country.

Aung San Suu Kyi is an honorary fellow of St Hughs College, Oxford. In 1990 she was awarded the Thorolf Rafto Prize for Human Rights in Norway and the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought by the European Parliament, and in 1991 she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. In its citation the Norwegian Nobel Committee stated that in awarding the Prize to Aung San Suu Kyi, it wished to honour this woman for her unflagging efforts and to show its support for the many people throughout the world who are striving to attain democracy, human rights and ethnic conciliation by peaceful means.

Aung San Suu Kyi is also author of several books, including Freedom from Fear, which was edited by her husband, Dr Michael Aris, and The Voice of Hope, both of which are published by Penguin.

Fergal Keane, OBE, is one of the BBCs most distinguished correspondents and has been named reporter of the year on television and radio. His books are The Bondage of Fear, Season of Blood, winner of the 1995 Orwell Prize, and Letter to Daniel, all published by Penguin.

Introduction

by Fergal Keane

On the morning of my ninth wedding anniversary I found myself unexpectedly rushing to catch a Thai Airways flight to Rangoon, the Burmese capital. The plane was crowded with journalists who had heard, like me, that the Burmese opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi had been released from house arrest after six years. I was preparing to enter the country on a tourist visa, having been told by Burmas representatives in Hong Kong that I would have to wait several days for an official journalists permit. Thus as our plane came in over Rangoon, and I saw the still-flooded paddies beyond the city and the first golden temples, I was preoccupied with simply getting into the country and getting out fast with the story. At that stage I knew little about the internal politics of Burma or its history. Like everybody else on the aircraft I was frantically reading the news clippings about Aung San Suu Kyi and her jailers, the State Law and Order Restoration Council or SLORC as they are known and dreaded by the Burmese people. What I quickly gleaned was that Aung San Suu Kyi was not merely the leader of the opposition. In actual fact she was the leader of the party which had won more than 80 per cent of the seats contested in an election called by the military back in 1990. This election took place a year after the army had shot many thousands of unarmed demonstrators and while Aung San Suu Kyi was under house arrest. Her National League for Democracy had been forced to campaign without its leader but had still managed to win a huge victory.

I had of course seen news reports about Burma on television and had frequently seen Aung San Suu Kyis photograph in the newspapers. The photographs had been taken while she was at liberty, in the months when she travelled the length and breadth of Burma rallying the people behind the NLD. The word charismatic was used a great deal by those who wrote about her. One of the stories told of how she had faced down an army officer who had given his men orders to shoot her. She had simply continued walking calmly down the road until another officer intervened and countermanded the order. But colleagues who visited Burma in more recent times warned me that the country was blanketed by a state of fear. People would not talk to journalists. The governments spies were everywhere. Telephone lines were unsafe and those who had attempted to approach Aung San Suu Kyis home on University Avenue had been roughly sent on their way by soldiers. As it happened, the atmosphere in Rangoon was considerably more relaxed on the afternoon I arrived. There were no problems at immigration or customs. A couple of thuggish-looking types wearing shades lurked around the entrance to the airport but they paid no attention to me. They were clearly waiting for somebody else.

Bearing in mind the warnings about spies, I kept the conversation with the taxi driver to a minimum of bland platitudes. A lovely country, I agreed. Pretty scenery. And then the driver noticed the paper I was carrying. On the front page of the Bangkok Post was a large picture of Aung San Suu Kyi. The driver smiled and said to himself: The Lady, the Lady. You like her? I enquired. We dont like her, sir, we love her, he replied. Thus was I introduced to the powerful affection which the ordinary people of Burma feel for Aung San Suu Kyi. It is a feeling which prompts thousands of them to risk their lives and physical freedom by attending rallies outside her home each weekend. I have asked numerous people teachers, peasants, monks, even a few off-duty soldiers why there is such a well-spring of feeling for Aung San Suu Kyi. After all, she has been actively involved at the forefront of Burmese politics for less than a decade nothing like the lifetime of political struggle of her fellow Nobel laureate Nelson Mandela. Perhaps the most eloquent answer to my question came from an old man, standing drenched to the skin outside Aung San Suu Kyis house on the day after her release. We come here because we know that we are the most important thing in the world to her. She cares about us. To a people who suffer continually the brutality of one of the worlds most odious regimes, the notion that a leader might actually care about them, and risk her own freedom to fight for theirs, is indeed unusual.

Later, when I came to meet Aung San Suu Kyi and we became friends, I began to appreciate the singular qualities which inspired such devotion among her followers. Chief among the attributes which make her a remarkable leader in our times is a deep humanity, a gift for understanding and embracing the pain of others as if it were her own. Much of her time these days is spent listening to the voices of ordinary people, who risk arrest by coming to her compound to talk about their problems. Poverty, military oppression, the hunger for arable land, all are discussed with the supplicants who come to the house by the lake. None are turned away without being given a hearing. Now reading these wonderful letters from Burma, written between November 1995 and December 1996, in the few spare moments she has managed to find away from public life, I am again touched by the sense of decency which shines through. In a world so massively consumed by greed and hatred, her plea for a simpler and more person-centred politics is breathtakingly refreshing. In one of her letters she writes: