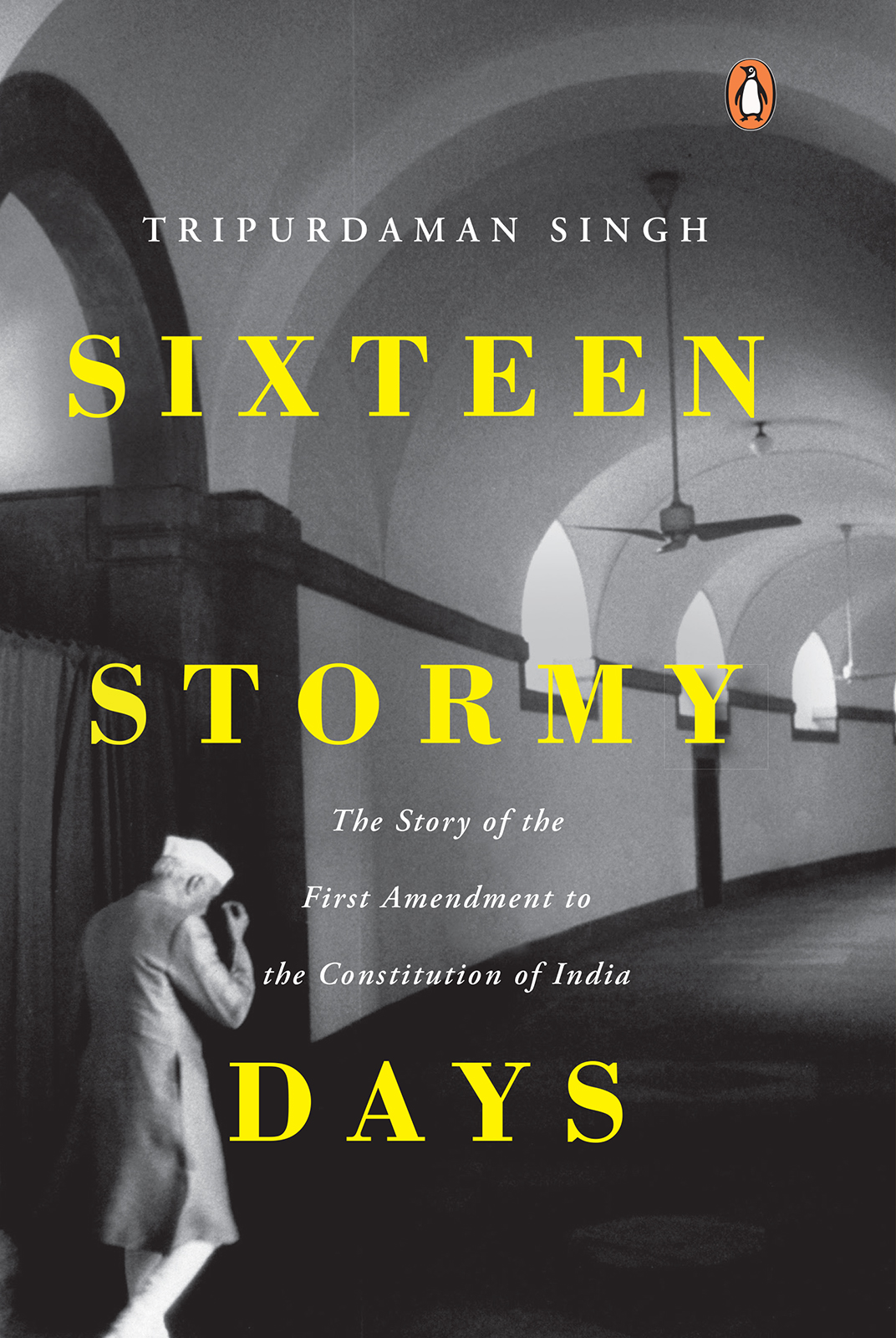

Tripurdaman Singh - Sixteen Stormy Days

Here you can read online Tripurdaman Singh - Sixteen Stormy Days full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Penguin Random House India Private Limited, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Sixteen Stormy Days

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Random House India Private Limited

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sixteen Stormy Days: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Sixteen Stormy Days" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Sixteen Stormy Days — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Sixteen Stormy Days" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Somehow, we have found that this magnificent constitution that we had framed was later kidnapped and purloined by lawyers, thundered Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru as he moved the Constitution (First Amendment) Bill to be referred to a standing committee in Parliament on 16 May 1951.

He had every reason to be angry. Land reform, zamindari abolition, nationalization of industry, reservations for backward classes in employment and education, a pliant pressthese were the shining new schemes of social engineering that were going to remake the social and political fabric of the new nation.

And yet, three-and-a-half years since Independence, when the Congress party held unchallenged sway over the state, these flagship schemes had almost ground to a halt. The governments entire social and economic policy was in danger of failing. Armed with Part III of the new constitutionguaranteeing the fundamental rights of citizenszamindars, businessmen, editors and concerned individuals had repeatedly taken the Central and state governments to court over their attempts to curtail civil liberties, regulate the press, limit upper-caste students in universities and acquire zamindari property. Over the fourteen months the constitution had been in force, the courts had come down heavily on the side of the citizens and struck mighty blows against the government.

In Delhi, the governments attempt to censor The Organiser, an RSS newspaper, had been countermanded.

In Madhya Pradesh, the Central Provinces and Berar Regulation of Manufacture of Bidis Act, that controlled and regulated the production of bidis, was held void and declared inoperative by the Supreme Court because it violated the right to carry on any trade or profession. In the courts and in the press, the government had repeatedly come in for withering criticism.

The entire Congress programme to remake India and consolidate its position had encountered formidable roadblocks: fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution, tenacious citizens, a belligerent press and a resolute judiciary determined to vigorously uphold fundamental freedoms. By early 1951, with elections looming and major initiatives continuing to run afoul of constitutional provisions, Prime Minister Nehru had grown increasingly exasperated with his plans being thwarted. Impatient and stubborn at the best of times, he chafed at the temerity of those that came in his way. The situation, in his own words, was intolerable.

The very same Constitution that the Congress had championed barely twelve months ago now became its bugbear. The very freedoms so ceremoniously granted on 26 January 1950 were now major stumbling blocks on the road to progress. The very makers of the Constitution now railed against too much liberty. Nehrus solution was straightforwardto bend the Constitution to the governments will, overcome the courts and pre-empt any further judicial challenges. In his view, wider social policy had to be determined by the government, and neither the courts nor the Constitution could be allowed to stand in the way.

Declaring that the courts stressing fundamental rights over the Directive Principles of State Policy and resultant social changes was hindering the whole purpose of the Constitution itself,

In a nutshell, the bill proposed several major modifications. It sought to introduce new grounds on which freedom of speech could be curbedpublic order, the interests of the security of the state and relations with foreign states. In the original constitution, these had been limited to libel, slander, defamation, contempt of court and anything that undermined the security of the state or tended to overthrow it. With the addition of the three nebulous new provisos, left to the government of the day to define, the right to freedom of speech and expression was to be drastically curtailed.

The bill sought to enable caste-based reservations by restricting the right to freedom against discrimination from applying to government provisions for the advancement of backward classes. Nothing would now prevent Parliament from creating special measures for backward communities, and none of these measures would be legally challengeable even if they breached any of the fundamental rights provisions. It sought to circumscribe the right to property and validate zamindari abolition by adding two new articles empowering the state to acquire estates without paying equitable compensation and ensuring that any law providing for such acquisition could not be deemed void even if it abridged this right. And finally, it sought to introduce a special schedule where laws could be placed to make them immune to judicial challenge even if they violated fundamental rightsa veritable repository of unconstitutional laws beyond the courts purview, a schedule described by the jurist A.G. Noorani as an obscenity created by wilful resolve.

The amendment proved to be a lightning rod for criticism and galvanized opposition to the Congress regime. Cutting at the very root of the fundamental principles of the constitution, charged the leader of the Opposition, S.P. Mookerji, And these were only the opening salvos. What unfolded over the next two weeks, as Parliament debated and then passed the Bill, can only be described as the first battle of Indian liberalism, as a disparate band of forces took up the fight to preserve the expansive freedoms the Constitution had originally granted.

Outside Parliament, the press, the intelligentsia, traders, constitutionalists and lawyers joined the battle. Newspapers sharply criticized the government. Opinion pages bristled with indignation. The All India Newspaper Editors Conference and the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry protested against the move, passing resolutions and sending delegations to meet the prime minister. Across the country, bar associations and the legal fraternity came together to oppose any amendments to civil liberties, and retired judges organized and attended protest meetings. An outraged young lawyer (and future judge), Rajinder Sachar,

Inside Parliament, a small and scattered but vocal and spirited Opposition took up the challenge of defending civil liberties. Luminaries of the freedom movement and the original Constituent Assembly, such as Shyama Prasad Mookerji, Acharya Jivatram Kripalani, Hari Vishnu Kamath, Naziruddin Ahmed and Hriday Nath Kunzru, savaged the Bill when it was presented and launched blistering attacks on the government. Nehru challenged them to combat here, in the marketplaces, in the country, everywhere and at any level.

Lest anyone be deceived, this was no storm in a teacup. Several Congress parliamentarians took the government to task. Others pointed out that it was inappropriate for an unelected provisional parliament to amend the Constitution. Initially, even Nehru was daunted. The Bill for the amendment of the Constitution is meeting with a good deal of opposition in the press and elsewhere, he wrote to his chief ministers, but we hope to get it through, even though it requires a two-third majority. Congress whips were pressed into action to try and shepherd their flock, and prevent the bill from being criticized in the House. Despite the strong pressure, however, several conscientious objectors refused to budge. Still others criticized the government in Parliament, but eventually chose to abstain when the House voted.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Sixteen Stormy Days»

Look at similar books to Sixteen Stormy Days. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Sixteen Stormy Days and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.