I am so very lucky, and very happy, to have you by my side. It really is as simple as that.

Thank you for your patience, good humour, those wonderful grandchildren and, above all, your unconditional love. No father could ask for more.

I ts entirely possible that you may know what an MP actually does. After all, the work of an MP is by its very nature a very public job. Barely a day goes by when something they have done, said or been challenged over is not in the news. And thats not accounting for when a scandal erupts, usually over money, sex or both.

I do, however, want to add a note of caution.

When I became an MP in 2010, I thought I knew not only what I wanted to do but also how best to achieve those goals and what would be expected of me by constituents, party and Parliament. By 2015, when I left the House of Commons, I finally understood how bloody wrong and naive I had been.

So, who are these MPs and what do they do? Why do over 32 million people turn out to elect their representatives in the first place when, if opinion polls are to be believed, over two thirds of the country dont rate or trust them? What do we really expect from them, given that most of the time we barely give politics a second thought? Lets face it, most people have better things to do than think about MPs for more than a few seconds a day. We Brits tend to think about who is making the next cup of tea more than we think about who is making our laws.

You, however, are different.

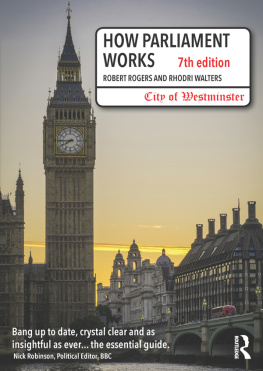

While quite a lot of people think that MPs as a breed deserve abolition, and that the Houses of Parliament should be turned into a theme park, you on the other hand seem prepared to withhold judgement. After all, you have in your hands a book about Parliament and MPs. Dont worry, Ive made the cover as harmless as possible to make sure you dont get disapproving stares from others as you read. With any luck, they may think youre reading a 60s spy novel or the latest offering from Jeffrey Archer.

Let me put my cards on the table, though.

I love the institution of Parliament and believe it serves our country well. Rest assured, I have not seen fit to write a dull defence of MPs, more a journey through both Westminster and the constituency that will help you reach your own conclusions on that score. I hope that you may also be left reflecting on the unique complexities of everyone involved in this extraordinary democratic process: the constituents, the ministers Prime Ministers, even and of course the humble backbencher, a mantle I happily and proudly wore for five years.

In writing this book, I have not set out to educate you on the processes of Parliament or to be included in the GCSE Politics syllabus. If it is deemed fit for academic reading lists, I will have failed. Instead, it will, I hope, cast some light onto a system that has outlived you and I some ten times over and seen the country through more challenges than any other institution or person could weather, except perhaps for the monarchy. All this despite the many foibles and weaknesses of both individual Members of Parliament and the very Palace of Westminster itself.

As you will discover, this isnt a political book; its a book about political life. Its the inside story of a backbench MP, devoid of ministerial restriction but packed, I hope, with a little humour, a few anecdotes, plenty of irritation and some purpose. Oh, yes, and the odd kiss and tease.

Finally, let me assure you, no constituents or fellow parliamentarians were harmed during the making of this book. Although when you have read it, you may wonder how on earth that was the case.

I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it.

Nick de Bois

Hertfordshire

January 2018

Y ou are not an executive who can make and enforce decisions. You are a legislator who votes on making laws.

You are not qualified or trained on how to be a guidance counsellor, but you are often mistaken for an elected councillor and expected to do what a councillor should do.

You are not a housing officer, benefits clerk, bank manager or trading standards officer, but you are often expected to provide a new home, sort out benefits, provide a loan or settle a dispute about a computer game bought for little Jimmy that doesnt work.

You are, however, a bloody good listener. Well, most of the time, that is.

So, what are you? You are in fact a 21st-century Member of Parliament representing a population of about 100,000 good folk from your constituency by taking your seat in the oldest and most established of all the worlds Parliaments and yes, quite frankly, probably the finest Parliament in the world, despite what you may read or hear in the media.

You are elected by a simple majority from roughly 50,000 people who turn out to vote and mark their X by your name at a general election. Some do it wholeheartedly and generously, some begrudgingly, and even a few by mistake, but most do it with a sense of hope that you will be able to make a difference somehow.

Unfortunately, when as a new Member of Parliament you walk through the Members Lobby, dwarfed by the imposing statues of Lloyd George, Churchill, Attlee and, yes, the magnificent Margaret Thatcher, filled with a vision of how you will leave your mark on this place, this nation and this government, what you are almost certainly unaware of is that your constituents, your government, the press and the very institution of the Palace of Westminster have other plans for you. And thats before the odd fruitcake or two who persistently latch on to you.

So it was for me in May 2010 when, with an unimpressive and insecure majority of 1,692, I began the most marvellous journey of a lifetime as I met head-on the bizarre, the inexplicable, the touching, the shocking, the vitally important and, yes, thank God, lots of utter bollocks as well.

I confess, I went to a boarding school, more commonly known as a public school. Or, as the Daily Mirror would have you believe, a toffs training ground.

To be fair, Culford School was no Eton, but it did a pretty good job of making this son of an RAF family fairly independent-minded, if not an academic achiever (one A-level grade E and five mediocre GCE O-levels). Although I had become quite fond of the place by the time I left in June 1977, I had thought that was the last I would see of an establishment built around patronage, prefects and privilege. A place where new bugs and old bugs (slang at the time for boys) were the inherent dividing line, where certain individuals were singled out, often inexplicably, for preferential treatment or rank and, where above all else, one man, the headmaster, carried absolute authority and the ability to dispense advantages on the favoured few. Fast forward to 2010 and thirty-three years later, as I began my first day in Westminster, it all came flooding back to me.

On any first day at school, the first thing you are shown is your coat hanger, and Parliament is no different.

During the introductory week, the doorkeepers of the Palace of Westminster, who are the most resplendent and amongst the most knowledgeable people in the place, are hosts for any MP who wants a guided tour. And that tour begins in the cloakroom.

Here, sir, is your coat hanger, with your constituency name, Enfield North, above it. (A gentle reminder that I was here on a temporary basis, hence the constituency name on the tag, rather than mine.)

Strange, I thought. Every coat hanger in the place, some 650 to be precise, had a pink ribbon attached to it with a small loop. I vaguely thought it might have something to do with the hugely successful Breast Cancer Awareness Day campaign.