Acknowledgments

This work is the result of a long period of research begun a decade ago, when I set out to perform a study on Italian-language anarchist periodicals published in the United States. That project did not materialize, but my interest in the subject continued and led me, first, to edit the Italian edition of Paul Avrichs essential book, Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background , released by Nova Delphi in 2015, and then to participate in a series of conferences, conventions, and volumes by multiple authors commemorating the ninetieth anniversary of the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti.

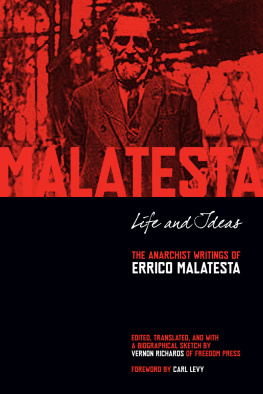

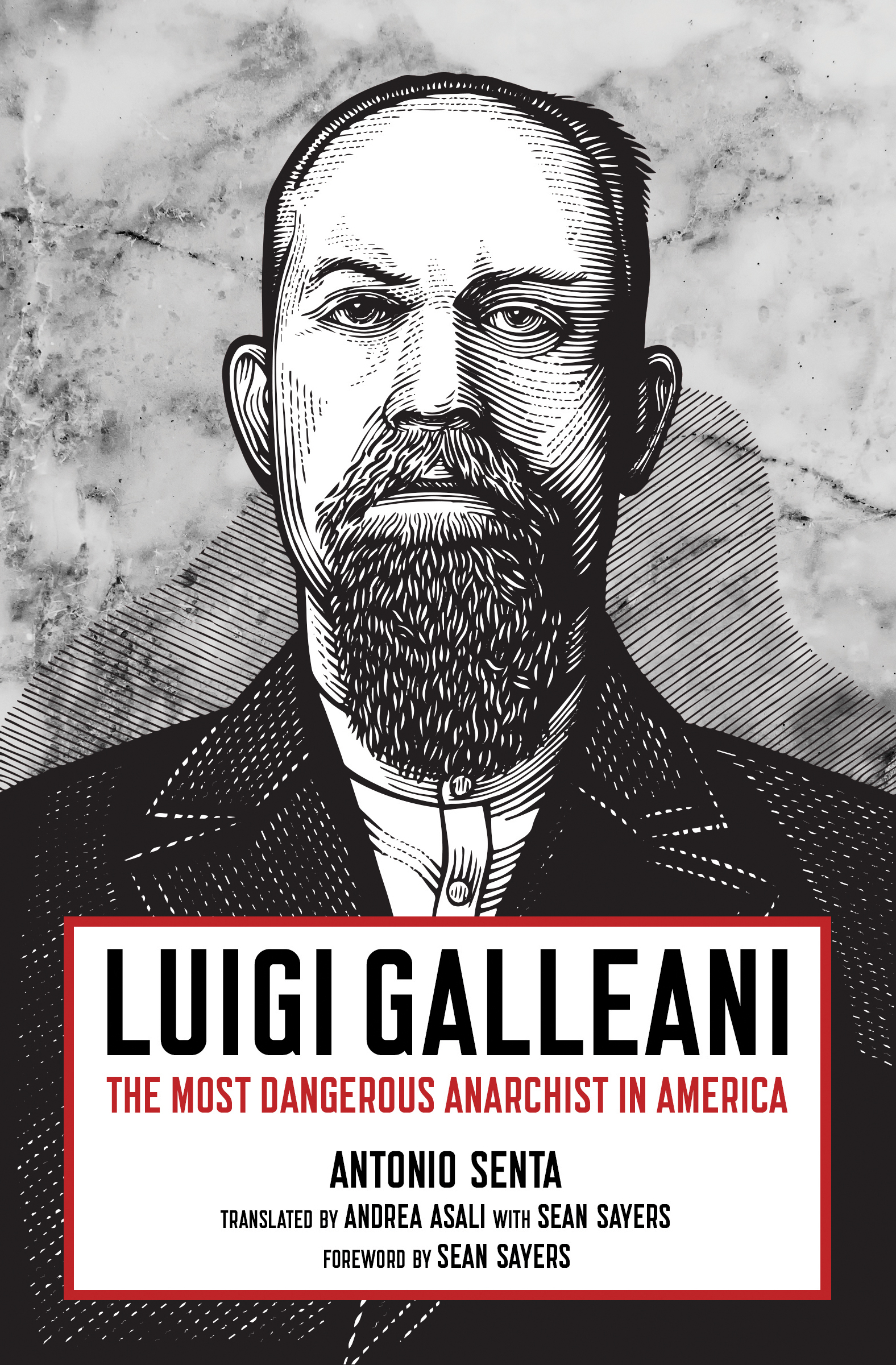

The book you hold in your hands aims to reconstruct the life and ideas of Luigi Galleani. Starting with his individual experiences and original points of view, it also aims to reconstruct the social and cultural climate subversives lived within for fifty years (18801931), in Europe as well as the United States. An exciting tableau emerges, and every reader will make their own independent evaluation of it. The events are framed by the complex relationship between insurgents and the exploited, or in other words, between a political vanguard and the labor movement. Galleani continually addresses a proletariat among whom his propaganda takes root, in different places and times. Even the most extreme positions, and consequent actions, are not extraneous to the context and struggles of workers. My hope is that the following pages will help the reader better understand many historical aspects of the anarchist movement and its underlying principles, so we can avoid hasty judgments on subjects considered obscure, odd, or marginal.

This is the second biography on the insurgent from Vercelli, after the one written in the 1950s by Ugo Fedeli, activist, archivist, and autodidact historian whose life and papers I studied for seve ral years.

No archives dedicated to Luigi Galleani have survived to this day, not even a book archive. The heritage of a life spent roaming has been irremediably lost, particularly due to continuous police attention and repression. Nevertheless, I was able to retrace written material by and about him in various archives.

About seventy original letters written in French and unpublished, conserved in the Jacques Gross Papers at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam, were first and foremost useful. Several folders from the Ugo Fedeli Papers, also kept at the Institute in Amsterdam, likewise shed light on the subject, containing the material Fedeli used to prepare his biography on Galleani. The LAdunata fund at the Boston Public Library was helpful as well. Police documents kept at the Central State Archives in Rome, the State Archives in Massa and Turin, the Historical Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Rome and the National Archives in Washington, in addition to periodicals and other printed material found in Amsterdam, Boston, the Archiginnasio Library in Bologna, the Berneri-Aurelio Chessa Family Archives in Reggio Emilia, and the Gallica of Paris, today partly digitized and available online, were all o f service.

Although critical literature and secondary sources were duly considered, I wanted to give primary attention to the perspective of the most dangerous anarchist in America, insomuch as I could deduce from the sources most closely linked to him, his writings, letters, accounts from his comrades and family members. This seemed to me the most interesting and meaningful way to reconstruct the kind of lif e he led.

It would have been much more difficult to write this book without the generous contributions of so many people. Sean Sayers followed the research step by step and inspired me on many an occasion, helping me, among other tasks, to source material in the archives of Boston and Massa, and sharing documents, photos, and family memories. Fiamma Chessa made available the documentation kept at the Berneri-Chessa Archives. Tomaso Marabini did the same with his historical popular archive. Jack Hofman helped me with the research at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam, as did Anna Manfron at the Archiginnasio in Bologna. Over several years, Tobia Imperato sent me what he found on and by Galleani. Gino Vatteroni shared his research on emigration from Carrara to the United States. Davide Turcato was always available to provide recommendations and advice, as well as bibliographical suggestions. Marianne Enckell, Gianpiero Bottinelli, Edy Zaro, and Davide Bianco were very helpful in reconstructing the periods Galleani spent in Switzerland and France. I exchanged information and impressions on Galleanis time in Turin with Marco Scavino, and received information on Galleanis years spent in exile in Pantelleria from Sandro Casano and Giuseppe La Greca. I discussed the anarchist movement in the United States and the role of activists such as Galleani, Alfonso Coniglio, and Umberto Postiglione with Edoardo Puglielli, and the role of the press in Italian-language political transatlantic emigration with Andrew Hoyt. David Bernardini helped me understand several aspects of German-language anarchist emigration to New York. Giorgio Galleani from Ventimiglia shared information on the noble origins of the Galleani lineage. Robert DAttilio, through Sean Sayers, also encouraged my research. Thanks to Ferdinando Fasce for the epistolary exchanges on the subject of Italian immigration in the United States, Enrico Ferri for information on the Armenian revolutionary movement, the Giuseppe Pinelli Archive collective of Milan and Franco Schirone for bibliographical information, and Massimo Ortalli for having publicly encouraged me, several years ago, to write a biography on Galleani. The aforementioned Sayers, Imperato, and Turcato had the patience to review a draft of the book and provide feedback, as did Carla De Pascale and Elena Suriani. I would like to acknowledge and thank everyone mentioned, with the shared awareness that only I am responsible for what is written in the following pages. I dedicate this work to Jacopo, the newes t arrival.

Ant onio Senta

(Dece mber 2017)

Foreword

I am Luigi Galleanis grandson, he was my mothers father. I did not know him, he died well before I was born. My mother told me only a little about him. She was not at all unwilling to talk about him, but she would do so only when asked; and, with the arrogance of youth and to my great regret, I did not ask much about him. So when I was growing up I had only a sketchy awareness of his life and activities, and it was not until after my mother died that I started to become interested in his life. When, at last, I did begin to look into my familys history, one of the first steps I took was to look to see if there was anything about him on the Internet. I was amazed to discover how much there was there, and to realize what an important person he had been and what a remarkable life h e had led.

As Antonio Senta describes in these pages, he was born in 1861, in Vercelli (Piedmont), one of four children in a respectable middle class, Catholic family. His father was an elementary school teacher. Galleani was evidently a spirited and independently minded person even in his youth. According to family legend, he was pressured by his father against his wishes into studying law at the University of Turin, but he didnt take his degree, by that time he was already actively engaged in radical politics.