The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my late mother, Emily Campbell Brown, a small-town Southern girl who taught my brothers and me about service and justice.

To Connie, who makes the fight bevery day.

And to our future warriors for justice: Clayton, Leo, Jackie, Carolyn, Milo, Ela, and Russell.

We must come to see that human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

F INALLY, IT WAS THE FRESHMENS TURN. Ten of usnine Democrats and one Republicanwandered around the big hall, surveying where we might sit. We talked about location: which row to sit in, whom to sit next to, which desk was closest to the frontit was all perhaps a bit too reminiscent of high school.

It suddenly occurred to me: there were no bad places to sit. No pillars to sit behind. No obstructed views. We were on the floor of the United States Senate.

At the freshman orientation a couple of months earlier, senior senators had shared with us some stories and traditions of the Senate. One of those traditionsreminiscent of middle schoolis that most senators at some point in their careers carve their names in the drawers of their desks in the Senate chamber.

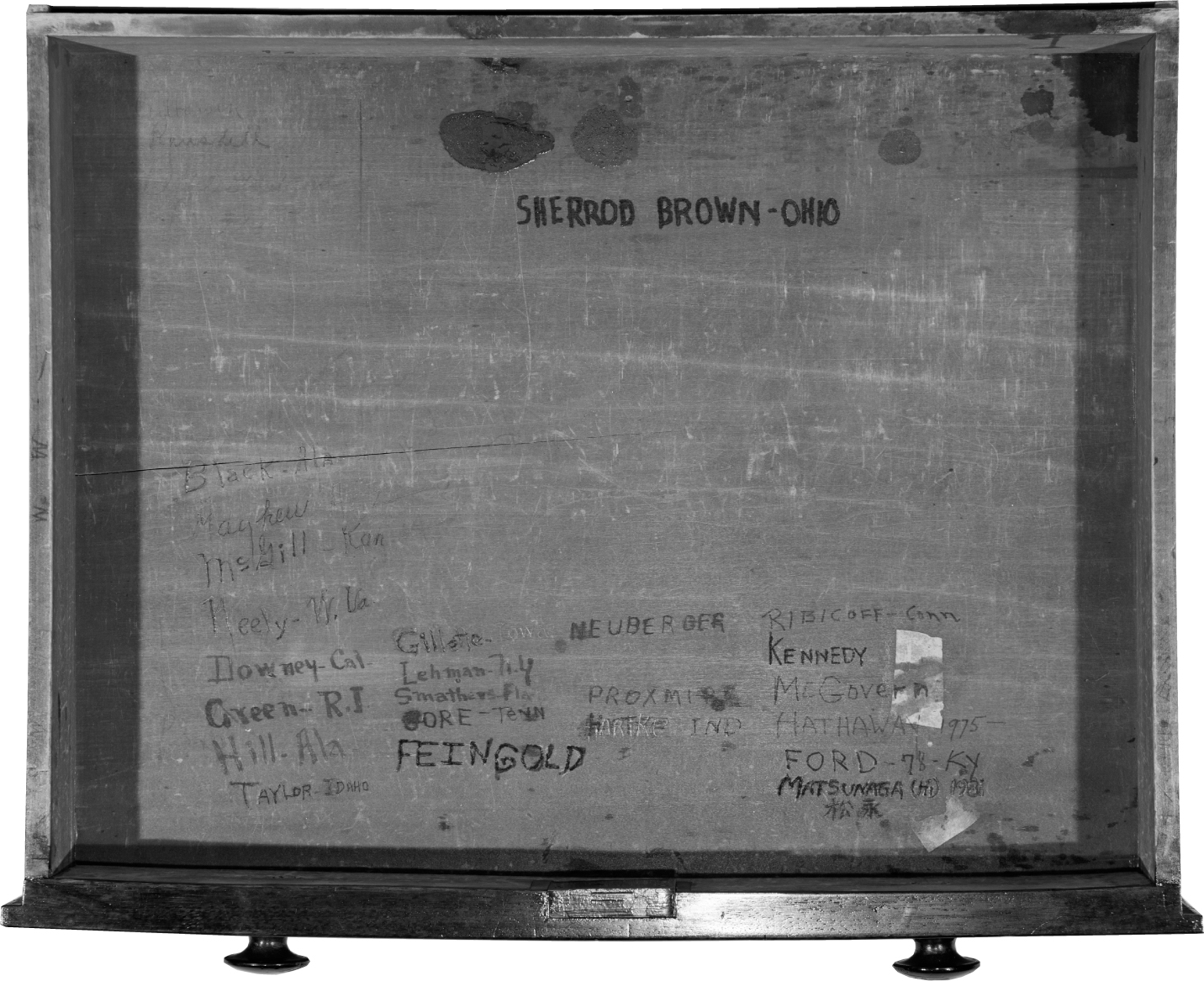

So, a bit sheepishly, with these carvings and this history in mind, I pulled out drawer after drawer in desk after desk, pushing aside the clutter of stationery, legislation printouts, and committee reports to read the names that were carved on the inside bottom of each drawer.

At the fourth desk I approached, something felt different. I knew almost every name carved in the drawer. I read through the names of Desk 88Black of Alabama, Gore of Tennessee, Lehman of New York, McGovern of South Dakota, andI broke off, curious. Between McGovern and Ribicoff of Connecticut, the desk drawer had only one word: Kennedy. No state, no first name. I called out to Senator Edward Kennedy and asked him to look at the desk. Ted, which brothers desk was this?

He looked down at Desk 88. It must be Bobbys, he said. I have Jacks. I had found my Senate home. My chief of staff, Jay Heimbach, informed the clerk of the Senate that Desk 88 was the one I wanted.

WHAT DREW ME to the names at Desk 88 was the idea that connected them: progressivism. Its a political ethic that had driven not only my votes in Congress (I joined the House of Representatives in 1993 and reached the Senate in 2007) but also my decision to run for office in the first place. Over the past century, progressives have stood for labor rights, civil rights, stronger antitrust laws, womens rights, a higher minimum wage, health and safety regulations, a steeply graduated income tax, child labor protections, and workers compensation. More recently, progressives have fought for abortion rights, universal health care, strong environmental laws to combat climate change, equal rights for gay and transgender Americans, gun safety laws, consumer protections, and a ban on political contributions from corporations.

Progressives of all generations, and certainly those who sat at Desk 88, share a revulsion at injustice and wage inequality and wealth disparity; most progressives are bound together by a deep respect for the dignity of work and, in Tolstoys words, the fundamental religious feeling that recognizes the equality and brotherhood of man. Progressives typically share a common suspicion of concentrated power, especially private power.

Some of those who sat at Desk 88 played crucial roles when the country was in the midst of progressive times. Others, at great risk to their political careers, espoused progressive principles in more difficult eras, when the country was in a particularly conservative, sometimes dark and angry mood.

Often the great achievements of the occupants of Desk 88 took place somewhere elsein the ornate hearing rooms of the Russell Senate Office Building, in union halls or church basements, at veterans lodges or in school auditoriums. But sometimesand there are examples in this bookthe desk itself bore witness to a turning point in progressive history. The greatness of these senators was most evident when they spoke out and fought against the special interests that have always had too much influence in our government.

Like most legislators throughout U.S. history, the senators of Desk 88 have been disproportionately white and male. The Senate historian believes that no woman has yet called Desk 88 hers. Even as this book celebrates the men who articulated and achieved progressive goals, its final chapter will acknowledge the work still to be done and highlight a new generation of progressives working for equality and opportunity.

Progressive movements arouse the public as they fight the abuse of power by oil companies, Wall Street, the tobacco industry, and huge pharmaceutical firms. They challenge the dominance of the big banks and Big Oil and the gun manufacturers, and they attack entrenched racism and sexism. They want to reform a broken system under which powerful interest groups almost always have their way in the halls of Congress and in state legislatures across the country. They speak out against what William Jennings Bryan labeled predatory wealth.

Fundamentally, progressives want an America where the voiceless are heard in the government, where those without wealth or power have a government that represents them. And as progressives fight for civil rights and womens rights, for LGBTQ rights and labor rightsin short, the fight for equality is what defines a progressivewe know that progress has never come easy, even in the United States of America.

Almost two decades ago, I addressed a Workers Memorial Day rally in Lorain, Ohio. I stood in front of a fifty-foot-high pile of black iron-ore pellets where the Black River empties into Lake Erie. After the event, the steelworker Dominic Cataldo handed me a lapel pin depicting a canary in a birdcage. This pin, he told me proudly, symbolizes our decades-long fight for worker safety. Ever since, Ive worn my canary pin to honor the millions of Americans who have fought for traditional American values, and to celebrate the dignity of work. In the early days of the twentieth century, more than two thousand American workers were killed in coal mines every year. Miners took a canary into the mines to warn them of toxic gases; if the canary died, they knew they had to escape quickly. It was a warning system built out of desperation. With no trade unions strong enough to help and no government that seemed to care, the miners were on their own.

Americansin their churches and temples, in their union halls and neighborhood organizations, in the streets and at the ballot boxfought to change all that. Our progressive forebears convinced our government to pass clean air and safe drinking water laws, to approve auto safety rules and protections for the disabled, to enact Medicare and civil rights and consumer protections, to create Social Security and workers compensation, to sponsor medical research and build airports and highways and public transit and municipal water and sewer systems. Every accomplishment, every step forward, came in the face of entrenched and powerful oppositionfrom Big Oil and Wall Street, from tobacco companies and pharmaceutical firms, from industries that poisoned our air and fouled our rivers. Tens of millions of Americans now live longer and healthier lives because activists all over our nation fought for our American values of fairness and economic justice.