2014 by James L. Buckley

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Encounter Books, 900 Broadway, Suite 601, New York, New York, 10003.

First American edition published in 2014 by Encounter Books, an activity of Encounter for Culture and Education, Inc., a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation.

Encounter Books website address: www.encounterbooks.com

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

FIRST AMERICAN EDITION

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Buckley, James Lane, 1923

Saving Congress from itself : emancipating the states and empowering their people / by James L. Buckley.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59403-775-7 (ebook)

1. Federal governmentUnited States. 2. United States. Constitution. 3. United States. Congress. 4. Intergovernmental fiscal relations. 5. Sovereignty. I. Title.

JK325.B84 2014

320.473'049dc23

2014019242

PRODUCED BY WILSTED & TAYLOR PUBLISHING SERVICES

Copy editor Jennifer Brown

Designer and compositor Nancy Koerner

For my brother

FERGUS REID BUCKLEY

IF MEN WERE ANGELS,

no government would be necessary.

If angels were to govern men, neither external nor

internal controls on government would be necessary.

In framing a government that is to be administered

by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this:

you must first enable the government to control the governed;

and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

JAMES MADISON

Federalist No. 51

Contents

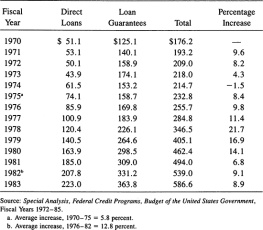

The United States faces two major problems today: runaway spending that threatens to bankrupt us and a Congress that appears unable to deal with long-term problems of any consequence. A significant source of each is a category of federal expenditures that has somehow escaped the notice it deserves. I refer to federal grants to state and local governments that have soared from $24.1 billion in 1970 to an estimated $640.8 billion in 2015. Grants-in-aid programs now absorb major portions of congressional time, thereby diverting Congress from its core national responsibilities, and they expend extraordinary amounts of money on objectives that are the constitutional concerns of the states. They also come freighted with detailed federal directives that deprive state and local officials of the ability to meet their own responsibilities in their own ways and undermine their citizens ability to ensure that their taxes will be used to meet local priorities rather than those of distant bureaucracies.

Congresss infatuation with grants programs has its source in a series of Supreme Court cases dealing with the Constitutions Spending Clause, which authorizes the federal government to collect taxes with which to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defense and general Welfare of the United States. The Court has construed the general welfare language as allowing Congress to induce states to accept federal directives regarding matters that fall within the states exclusive constitutional authority and that Congress itself has no power to regulate. The inducing takes the form of offers of federal subsidies for a vast range of state activities. If a state accepts the offer, it is bound by the regulations that come with the money. The states are free to decline the subsidies, but experience has demonstrated that free money is extraordinarily hard to refuse, however onerous the attached conditions.

As I will demonstrate at some length in my chapter on costs, those conditions can be onerous indeed, but they are by no means the only burdens that attend the acceptance of federal funds. To cite just a few, grants-in-aid programs add a costly layer of administrative expense at the federal level as well as increasing administrative costs to the states. The use of federal money triggers a host of mandates (such as the obligation to pay union wage scales on construction work financed with federal dollars) that can add substantially to what a state would spend on a particular project if it were only using its own money. Uniform federal rules deny states the ability to respond to local conditions as they would if free to handle the work their own way, and to the degree that state officials serve as implementers of federal policies, their citizens are effectively disenfranchised. They no longer have a voice in the design and management of projects that can have the greatest impact on their lives. And the proliferation of grants programs imposes major costs on Congress itself.

Senators and representatives are public servants, but they are also human beings who are subject to the ambitions and temptations that are part of our nature. They have discovered that the Courts construction of the Spending Clause provides them with the easiest way to ingratiate themselves to constituents and ensure their own reelection. They can now focus on their constituents most immediate concerns which, in the nature of things, will involve such parochial matters as the condition of local roads, the education of their children, and the safety of their communitiesmatters that are the immediate responsibility of their state or local officials. And so they respond to those concerns by introducing legislation that will authorize transfers of federal money to the local highway commission or school or fire departmentsubject, of course, to regulations that Congress itself has no direct power to impose. Creating grants is not only politically rewarding; it is safe. Few will object to a proposal for such motherhood issues as care for the homeless or better nutrition for kids. But any politician intrepid enough to propose a one-dollar reduction in Medicare payments in order to avert the programs bankruptcy will have AARPs 40,000,000 members calling for his scalp.

Next page