Getting High

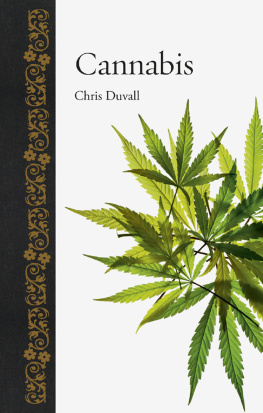

Mature female flowering top.

Getting High

Marijuana through the Ages

John Charles Chasteen

Rowman & Littlefield

Lanham Boulder New York London

To the Riamba Bros.

actual and honorary

living and dead

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB, United Kingdom

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2016 by Rowman & Littlefield

All original illustrations by Jeremy Hauch.

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chasteen, John Charles, 1955 author.

Getting high : marijuana through the ages / John Charles Chasteen.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-5469-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4422-5470-1 (electronic) 1. Marijuana abuseHistory. 2. MarijuanaHistory. I. Title.

HV5822.M3C43 2016

362.29'509dc23

2015027167

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Getting High

J ust wait until people our age are running things. Then everything will change. My sixteen-year-old friends and I had no doubts in the matter, around 1970. We assured each other, when we smoked marijuana, that a new dawn was inevitable in a world that was turning on. Marijuana, we believed, was a mind-expanding drug, somewhat like LSD, but much milder. The distinction was blurred, anyway, because we often used them together. We supposed that anyone, particularly anyone young, would change their attitude, spontaneously abandoning racism or support of the Vietnam War, for example, under the mind-expanding influence of the drug. Marijuana would help anyone see through sham and resist mind control by The System. The problem was getting them off booze, which dulled perceptions, rather than heightening them.

My sixteen-year-old friends and I viewed getting high and getting drunk as rough opposites. Marijuana was the drug of our tribe, the cool, long-haired, rock-music-listening, faded-blue-jean-wearing tribe. Pot, as we called it most often, made people peaceful. Alcohol belonged to the other tribe, exemplified by hard-hat construction workers who drank beer and threatened to beat up long-hairs. Alcohol stood for decadent tradition, and it made people violent.

We were wrong, of course, about the world, and also about pots irresistible persuasiveness. The world proved harder to remake than we had ever supposed. And the clarity of the 1970 tribes soon got muddled. By the 1990s, when I was a college professor sipping wine at faculty parties, men with long hair seemed more likely to be construction workers than students. Pot and beer no longer seemed like opposites, either. Marijuanas mind-expanding qualities had gotten lost.

Did it ever really possess them?

This book looks at marijuana in the long view of world history. It asks who used it, how, and why. Unlike most published versions of the drugs history, it places marijuana within larger historical patterns, such as migration, colonialism, and religion. It also keeps the marijuana/beer comparison in mind throughout. Above all, it asks whether marijuana really possesses mind-expanding powers.

A simple question, perhaps, but without a simple answer. For starters, the effects of the drug are variable and subjective. Consider the complexities. The same dose can affect different people differently, and the same person differently at different moments. Thats true of alcohol, too, but truer of marijuana. Its effect will vary according to expectations. To a degree, altered consciousness is always a blank screen onto which people project their expectations. Expectations play an enormous role in peoples reaction to any drug, of course, which is why placebos work. All this plays havoc with our attempts to characterize marijuanas mind-altering qualities in the abstract.

To understand the effects of mind-altering drugs, its better to ask how they are used in everyday life. Like alcohol, marijuana is often used just for fun. That is because, like alcohol, it is a euphoriant that triggers a surge of dopamine in the brains of users. Many recreational drugs are euphoriants, but their effects vary. The point of recreational use is simply to enhance the moment by stepping out of ordinary consciousness. Often, the fact that drugs somehow alter ordinary consciousness matters more than just how they alter it. Recreational use is generally social. It facilitates interpersonal bonding and generally greases the social gears. That is why, like drinking alcohol, smoking marijuana is very commonly a collective activity. In the late-twentieth-century United States, millions of people who smoked marijuana socially when they were university students, drank alcohol socially later in life, getting fundamentally the same thing out of it, a shared experience of release from the ordinary.

Still, the two drugs contrast in some respects. Alcohol depresses the nervous system; marijuana does not. At high doses, the drinker may experience difficulty walking or, famously, pronouncing words, and may black out or even, in extreme cases, die. Marijuana does not have those effects even at high doses. Instead, it creates distortions of normal perception and thought, as well as measurable deficits in reaction time, cognition, concentration, and memory. At high doses, it can produce visual hallucinations, such as the strobing arm movements that made my teenage friends look a little like Hindu deities. This is why pharmacologists tend to classify alcohol as a depressant, whereas they call marijuanas cognitive effects hallucinogenic. The hallucinogenic effects, not shared by alcohol, seem to explain marijuanas allegedly mind-expanding qualities.

Scientific research now demonstrates that marijuana is a medical drug, too. A hundred years ago we knew that, but wed forgotten. Cannabis has always figured in the pharmacopoeias of Europe and China, although these traditional medical uses, such as hempseed oil in the ear for earache, or cannabis-leaf poultices on a sprain, did not involve getting high. In addition, the euphoriant effect, when present, is a palliative that makes any ill more bearable. In the twenty-first century, research has revealed further medical uses. Marijuanas unique active ingredients, called cannabinoids (THC is the best known), have molecular shapes that fit receptors in our bodys hormonal communication systems, regulating mood and appetite, among other things. Thats how marijuana can calm chronic seizures or restore appetite and reduce pain and nausea in patients undergoing chemotherapy or enduring AIDS, for example. At least one therapeutic cannabinoid molecule, called CBD, is not mood-altering at all. Moreover, cannabinoids have few deleterious side effects. There are pharmaceutical imitations, but the synthetics do not seem to provide the same kind of relief. Because experiments with cannabinoids led to the discovery of the hormonal system they affect, researchers call it the endocannabinoid system. Note that this choice of name does not demonstrate that the human hormonal system evolved in conjunction with marijuana, however, as some have fantasized.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.