John M. Hart

ANARCHISM & THE MEXICAN WORKING CLASS, 18601931

University of Texas Press, Austin

The publication of this book was assisted by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/rp-form

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Library ebook ISBN: 978-0-292-76769-0

Individual ebook ISBN: 978-0-292-76770-6

DOI: 10.7560/703315

Hart, John Mason, 1935

Anarchism and the Mexican working class, 18601931.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Anarchism and anarchistsMexicoHistory. 2. Labor and laboring classesMexicoHistory. I. Title.

HX851.H37 335830972 77-16210

ISBN: 978-0-292-70400-8

Copyright 1978 by University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

History has two sacred dimensions : not to record falsely and not to fear the truth.

Clavijero, 1754

People! No more governments, down with tyrannies, on to social guarantees!

Plotino C. Rhodakanaty, 1861

We know more about the cave man than we know about the origins of socialism in Mexico.

Luis Chvez Orozco, 1936

Contents

This is a historical study of the Mexican anarchist movement and its crucial impact upon the Mexican working class between 1860 and 1931. It is not a history of the Mexican working class per se. That task of synthesis awaits the completion of numerous monographs treating regional and topical aspects of Mexican working-class history.

This study explores anarchism as an important factor in the development of the Mexican urban working-class and agrarian movements. It does not contend that anarchism, at any time, was the only ideology present within the Mexican working-class movement or that it commanded the ideological allegiance of a majority of either the urban or the rural workers. In explaining the history and defeat of anarchism it does not attempt to deny other forms of socialism or Marxism their rightful places in working-class history. It does destroy some old myths, but the fact that the nineteenth-century leaders, Plotino Rhodakanaty, Santiago Villanueva, Francisco Zalacosta, and Jos Mara Gonzlez; the twentieth-century revolutionary precursor, Ricardo Flores Magn; the Casa del Obrero founders, Amadeo Ferrs, Juan Francisco Moncaleano, and Rafael Quintero; and the majority of the Centro Sindicalista Libertario, leaders of the General Confederation of Workers, were anarchists who emphatically denied government does not detract from the richness of the socialist-Marxist tradition in Mexico.

The anarchist tradition is an extremely complex one. It involves various social classes, including intellectuals, artisans, and ordinary workers; changing social conditions; and political and revolutionary events which reshaped ideologies and thinking. During the nineteenth century the anarchists could be distinguished from their various working-class, socialist, and trade unionist counterparts by their singular opposition to government. In the early twentieth century the lines were even clearer because of hardening anarchosyndicalist, anarchist-communist, trade unionist, and Marxist doctrines. While acknowledging both my sympathy for libertarian ideals and my impatience with often self-defeating and otherwise unrealistic tactics and goals, I have made a sincere attempt to explain events and to achieve unattainable objectivity. It may not be possible, with all the emotion surrounding the topic, but I hope that this is a dispassionate assessment of the Mexican anarchists and their rightful place in Mexican working-class history.

I want to express my appreciation to the many colleagues and friends without whose help and advice this study would not have been possible. At the very inception of the project Dieter Koniecki of Mexico City selflessly made available extensive historical data obtainable only through private sources. Rudolph de Jong, Director of the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam, went beyond the call of duty in receiving me and then helping in the quest for many important documents. Stanley Payne and Fred Bowser both lent early encouragement and the inspiration to continue. James Wilkie made important suggestions regarding the twentieth century and George T. Morgan, Thomas Howard, and Laurens B. Perry lent considerable editorial advice. Special gratitude is reserved for Ingeniero Ernesto Snchez Pauln, who out of generosity and faith gave me six priceless photographs and access to thousands of crumbling rare anarchist newspapers dating from the early twentieth century. The University of North Dakota Faculty Research Committee assisted in the completion of this study with grants during the summers of 1971 and 1972. The University of Houston Faculty Research Committee provided a similar grant for the summer of 1974.

The editorial staff of The Americas was most cooperative in making available for publication in this volume material which originally appeared in the October 1972 and January 1974 issues of that fine journal. I owe a special thanks to the many Mexican scholars who have furthered the study of Mexicos working-class movements: among them are Jos Valads, Luis Chvez Orozco, Manuel Daz Ramrez, Rosendo Salazar, Luis Araiza, and Jacinto Huitrn. The pioneering work of Fernando Prez Crdoba in his unpublished licenciado thesis provided countless leads. Finally, many thanks to Lisa for her manuscript assistance and to Mary for her unflagging support and patient forebearanee.

John M. Hart

European Influences

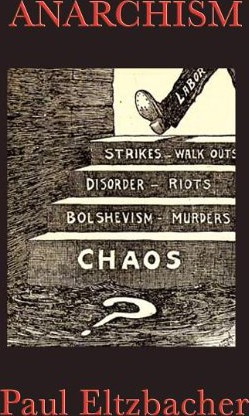

T he Mexican anarchist, or libertarian socialist, movement, which took root and grew during the fifty years prior to the Mexican Revolution of 1910, emanated from Mexicos own unique developmental process and from European influences. Representing but one of several responses to a half century of profound industrial, social, and political change, anarchism as both a doctrine and a movement suffers from popular misunderstanding. Despite its consistent denial of state authority, the simplistic conception of anarchism as violent opposition to all forms of government and as unrestrained individualism is totally inadequate for understanding the role of this ideology in the turbulent history of Mexicos urban and rural working-class movements and for measuring its impact upon that nations development. First developed in Europe, anarchist theory underwent substantial and often conflicting modifications prior to its importation into Mexico where further fragmentation of an already inconsistent body of thought occurred.

The precursors of anarchist ideology flourished during the eighteenth-century Enlightenment. The French philosophes in particular, by providing western society with an optimistic belief in progressin the perfectibility of man and his social institutionsbased upon human reason, created a climate of opinion conducive to the emergence of anarchist thought. Jean Jacques Rousseau, one of the Enlightenments most creative thinkers, contributed additional impetus in the form of an examination of the relationship of man to society and the state. His observation that man was born free and is everywhere in chains became one of the fundamental tenets of the anarchist movement, which sought to break the chains by reorganizing the economy and the polity in order to eliminate the oppressive power of the state.

The initial stages of specific anarchist ideologythe Holy Idea, as its more devoted adherents referred to itcan be traced to two fanatical proponents of individualism in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries: Max Stirner (pseudonym used by Kaspar Schmidt) in Germany and William Godwin in England. Stirner envisioned a union of egoists composed of independent supermen un-trammeled by legal fetters; Godwin, more importantly for the future course of anarchism, refined and developed Rousseaus contentions. Godwin traced the sources of human travail to bad government and inadequate institutions; he insisted that human reason, developed by means of education, could solve mans problems. Such refinement of mans comprehension would enable him to control his passions, seek equality and the simple life, and dispense with government. Later anarchists drew upon and refined these ideas of individualism and placed them within the social context of the Industrial Revolution.