Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Barbara Wilcox

All rights reserved

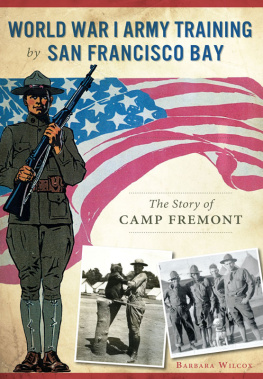

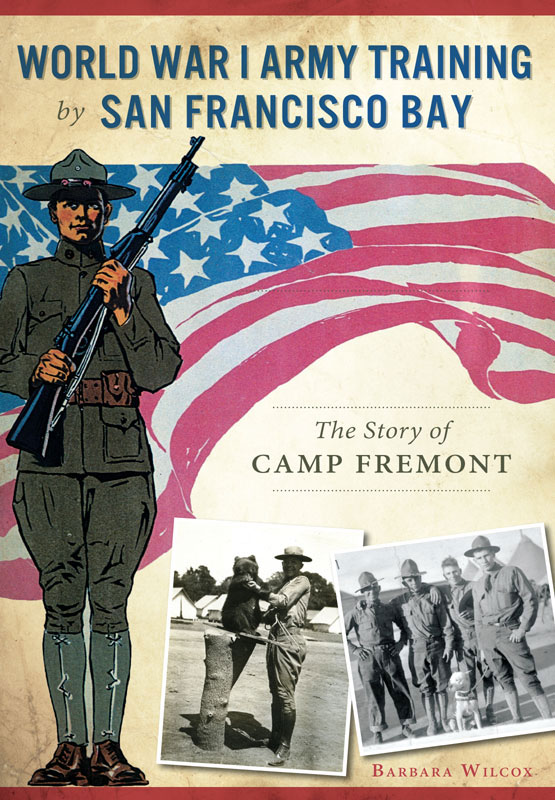

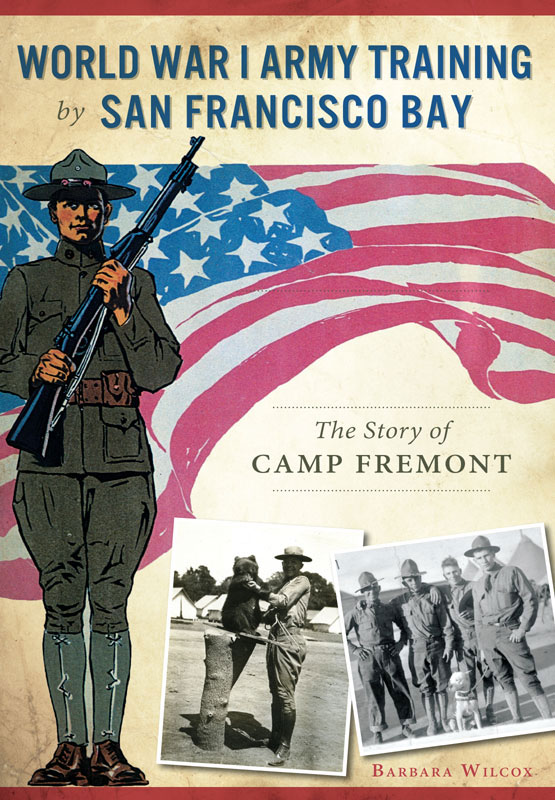

Front cover illustration: Detail from Political Poster Collection, US 5027, Hoover Institution Archives. Courtesy of Hoover Institution Library and Archives, Stanford University.

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.62585.633.3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015952926

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.891.0

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This little-known San Francisco Bay Area tale could not have been told without the help of many people. At Stanford University, I thank Professor David M. Kennedy of the Department of History, who read my work with the critical but forbearing eye of a great historian and a fine writer. Linda Paulson, associate dean and director of Stanfords Master of Liberal Arts program, expressed her confidence and support in myriad essential ways. Charles Junkerman and Stanfords Division of Continuing Studies funded my travel to the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Professor Peter Stansky and the Stanford Historical Society, particularly Laura Jones, Karen Bartholomew and Roxanne Nilan, recognized my project in its early stages and published a portion of the research. University archivist Daniel Hartwig and Tim Noakes and Mattie Taormina of the Stanford librarys Department of Special Collections and University Archives provided invaluable help. Rusty Dolleman and Nazima Chowdhary made wise suggestions. Perhaps most of all, support from my classmates kept me going.

Kathy Restaino and the Menlo Park Historical Association shared letters, photos and scrapbooks from their collection by soldiers and nurses who fondly remembered their Camp Fremont days. Much of this historically valuable material is published here for the first time. Crystal Miles was of great help in the University of CaliforniaBerkeleys Bancroft Library. The Hoover Institution Archives at Stanford; the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratorys Archives and History Office; Filoli Center, Woodside, California; Nancy Lund and the Portola Valley Historical Association; Bob Swanson; Curt and Christine Taylor; and Gary McMaster and the Camp Roberts Historical Museum all generously provided data that enhanced this work.

John Martin of San Diego, Will Lee of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Elena Reese, Dwight Harbaugh, Leslie Gordon and the late Tom Wyman generously shared their insights. John Spritzer, formerly of the U.S. Geological Survey, shared the desire to explore Stanfords hidden World War I tunnels that became the impetus of this project.

Dr. Nick Kanas and the California Map Society offered a speaking platform that was essential to conceptualizing the finished product. Megan Laddusaw at The History Press shepherded it through to completion.

Laurence Wilcox gave unflagging good humor and support.

Many other people gave help, advice and supporttoo many to name, but I thank them all.

INTRODUCTION

Not many homes in the Palo Alto hills have swimming pools. The foothills, especially in winter, are cooler than one might expect, with breeze from the Golden Gate reaching the region by afternoon and sending its tempering breath over the rolling grasslands and venerable oak trees. People in Silicon Valley think of themselves as doers, in any event, not as loungers by pools. For an invigorating swim, which is more in tune with how locals live, the Palo Alto Hills Golf and Country Club is down the street. But the client wanted a house with a pool, and so the contractor brought in equipment one morning in November 2010 and started, cautiously, to dig.

Pretty soon, the blade began unearthing hunks of long, rusty shells, deeply corroded, dozens of them, many with marble-sized shrapnel balls still nestled inside. A ringing ping of metal on metal heralded each new find. The contractor had heard this might happen and slowed the work pace even further. Then a blade connected with an object that made a distinctly thicker, robust thunk, and a bomb squad was called in.

This crew had encountered some of the few remaining physical traces of Camp Fremont, a World War I U.S. Army training camp that claimed roughly sixty-eight thousand acres of the San Francisco Peninsula, from San Carlos to Los Altos, at its peak in summer 1918. The camps nucleus was seven thousand acres leased from Stanford University and from private, mostly absentee, owners in what is now the small city of Menlo Park, where the camp was headquartered. It was one of thirty-two camps designated to train an army vastly enlarged after Americas April 1917 war declaration. Sixteen of these camps, including Fremont, had to be hurriedly built from the ground up. At Camp Fremonts peak, more than twenty-eight thousand men of the armys newly formed Eighth Division trained there for combat on the Western Front. They practiced trench warfare on a maneuver ground, complete with dugouts and underground galleries, on the site of todays Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) National Laboratory south of Sand Hill Road. They used an artillery range, where the crew digging a swimming pool found the unexploded shell in November 2010, stretching coastward from the Stanford property now called Dish Hill into the forested slopes between Los Trancos and Madera Creeks. There, on what now largely remains open space, men of Camp Fremonts Eighth Field Artillery Brigade spent a few intense weeks firing seventy-five-millimeter field guns from Dish Hill into the type of reverse slopes they hoped soon to conquer on the Western Front. It is ammunition from such a French 75quick and accurate, the famed workhorse of the Alliesthat excavators still occasionally find in the Palo Alto foothills today. Likewise, trenches and dugouts of Camp Fremont emerge after heavy rains as sinkholes among todays research installations and venture-capital firms. They are palimpsests from an earlier era of growth, innovation and change.

Few men who trained at Camp Fremont actually saw action in the Great War. Stationed on the West Coast, days by rail from the Atlantic ports of embarkation, the Eighth was the last of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) divisions to be put on trains before the November 11, 1918 Armistice. Some Camp Fremont units reached Europe in time to help with the occupation of defeated Germany or to build facilities for the AEFs return to the United States. Most got no farther than the Atlantic docks when peace broke out. That August, five thousand Camp Fremont men had been stripped from the Eighth Division and shipped across the Pacific Ocean to Vladivostok, Siberia, where they were kept until early 1920 as part of President Woodrow Wilsons failed Russian intervention to check Bolshevism there. Training draftees to fill their ranks probably contributed to the delay in Camp Fremonts deployment.

The strange tale of Americas Siberian intervention has been told elsewhere and is largely outside the scope of this book. Camps like Fremont, however, remain largely unexplored, both as physical places and as historical phenomena. Because Camp Fremont was evanescent, fading like most of its sister training camps into Americas postwar landscape, it is easy to dismiss as a curiosity. The tunnels of the trench maneuver ground are remembered fondly but with little sense of context by many locals, now elderly, who played in them as boys before Stanford sealed them in the 1940s. Yet the tunnels have a story to tell.

Next page