Copyright 2020 by Natan Sharansky and Gil Troy

Cover design by Pete Garceau

Cover photograph Nathan Roi

Cover copyright 2020 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

PublicAffairs

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.publicaffairsbooks.com

@Public_Affairs

First Edition: September 2020

Published by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The PublicAffairs name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020939476

ISBNs: 978-1-5417-4242-0 (hardcover), 978-1-5417-4243-7 (ebook)

E3-20200723-JV-NF-ORI

To our parents: Boris Shcharansky zl (19041980)

Ida Milgrom Shcharansky zl (19082002)

Elaine Gerson Troy zl (19332020)

While wishing long life to Bernard Dov Troy

And to our grandchildren: Those born:

Eitan

Yehuda

David

Avigail

Uri

Daniel

Ariel

and those yet to be born

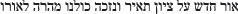

We are blessed to belong to this chain of transmission, from generation to generation, always trusting that a new light will shine unto Zion, hoping that we all will be privileged to be enlightened from it.

F ROM THE D AILY P RAYER B OOK

After living my life backward, the usual sequence seems overrated. Whenever I hear of friends separating after decades of marriage, I wonder, Maybe they did it in the wrong order. My wife, Avital, and I were separated one day after we married. We didnt see each other for twelve years, then lived happily ever after.

I was circumcised when I was twenty-five years old, not eight days old. So, unlike most, I could give my consent. And, two days later, when I joined yet another Refusenik protest, the KGB imprisoned me for fifteen days. Thus, the Soviet secret police enabled me to commune quietly with Abraham, the first Jew, who circumcised himself at the age of ninety-nine, and soon hosted angels in his tent.

Years later, after some other freed Refuseniks and I founded an Israeli political party, we thought up a fitting slogan. Promising that we are a different type of party, we go to prison first, we won more seats than expected.

Finally, at the age of sixty-five, I had my bar mitzvahfifty-two years late. The traditional Jewish rite of passage for boys is at thirteen. My belated ceremony was cost-efficient: I now had a squad of grandchildren to pick up the candy the guests would throw at me in celebration, so everything stayed in the family. Most importantly, I could better appreciate my Torah portions relevance and explain it to everyone without having my rabbi write my speech for me.

A year earlier, when I was sixty-four, one of my sons-in-law had been reminiscing about his bar mitzvah. I asked him what my Torah reading would have been. He looked it up, based on my birth date. I thought he was teasing when he answered a few minutes later: Its Parashat Bo, at the beginning of Exodus.

Parashat Bo? When Moses tells Pharaoh, Let my people go, uttering those mighty words that became the slogan of our struggle for freedom in the Soviet Union?

This cannot be a coincidence, I thought. I will have to have a bar mitzvah. Sixty-five seemed like a perfectly good agefive times thirteen.

On the appointed day, I read the first two parts of the Torah portion, with the proper trope, the traditional cantillation. Fortunately, my two sons-in-law stepped in and read the other five parts and the accompanying biblical passage from Jeremiah 43the Haftorahwhich envisions the Jews being redeemed.

Yet the ordeal wasnt over after the candies had been pelted and my young cleanup crew had arrived. I still had to make that speech. I analyzed Exodus 10:1 through Exodus 13:16, which peaks with the tenth plague, killing the firstborn Egyptians.

I asked, What makes this plague different from all the other plagues the Egyptians endured?

The first nine plagues seem like a Greek drama starring three protagonists: God, Moses, and Pharaoh. Aaron is a supporting player. The mass of Jewish slaves have no individuality. Their voices merge into one Greek chorus.

But for the big one, the tenth plague, every Israelite must act individually. Every adult in the community has to take a stand. Each Israelite first has to decide to be free, then act free. Each one rejects the Egyptian gods by slaughtering a lamb, an animal Egyptians worshipped. Then the Israelites publicly proclaim they no longer wish to live there, marking their doorposts with the lambs blood.

I explained that only by defying Egypt publicly could those slaves become free. And only through each individual declaration of independence could they join together in the national exodus. Real change occurs when each person stops being controlled by fear and starts acting independently.

All this paralleled the Refuseniks struggle against the Soviet system. Like Egyptian slavery, the Communist regime was designed to intimidate, to crush. Every Jew hoping to emigrate had to overcome overwhelming fear by soliciting an invitation from Israel, a Soviet enemy. Applying for a visa required seeking permission from each Soviet school and workplace that defined your life. Essentially, you shouted publicly, I dont accept your gods. I want to leave this country.

And what was the payoff? In Exodus, God offers the Jewish people the Jewish people. The Jews leave Egypt and seven weeks later receive the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai, accepting identity and freedom as a package deal. This would become one of our peoples main missions: balancing our right to belong and to be free.

Thirty-five hundred years later, I got the great payoff by joining that journey. Once I hopped aboard, I was never alone.

THREE PERSPECTIVES

Admittedly, this book reads like an autobiography coauthored with the American historian and Zionist activist Gil Troy. And the book traces my journey from nine years in Soviet prisons to nine years in Israeli politics, then nine years in Jewish communal leadership. But this book is not exactly a memoir. Immediately after my release from the Soviet Gulag in 1986, I wrote my prison memoir, Fear No Evil. As for my life in freedom, in Israel, I believe I am still too young to sum it all up. After all, I was only bar mitzvahed seven years ago.

This book tells the story of the most important conversation of my life: the ongoing dialogue between Israel and the Jewish people. I first backed into it on the streets of Moscow, when I joined the movement for Jewish emigration. It is an eternal, global, meaningful, and sometimes shrill conversation that saved my life decades ago. Today, it enriches both authors lives, as well as many others, by confronting questions about the meaning of faith, community, identity, and freedom. We believe that only through this dialogue can we continue our journey together. And thats why we believe it is a dialogue worth defending.