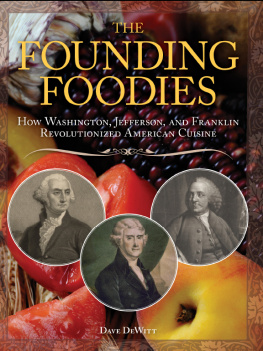

Copyright 2010 by Dave DeWitt

Cover and internal design 2010 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

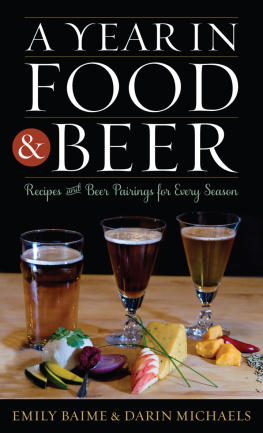

Cover design by Ponderosa Pine Design

Cover images Roy Hsu/Getty images

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought.From a Declaration of Principles Jointly Adopted by a Committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers and Associations.

All brand names and product names used in this book are trademarks, registered trademarks, or trade names of their respective holders. Sourcebooks, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor in this book.

Published by Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the publisher.

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

VP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to all my professors at the University of Virginia, 1962-1966, without whom I could never have completed this project.

Acknowledgments

H illel Black, my first editor at Sourcebooks, now retired, who taught me a few things about writing more interesting nonfiction. Joseph Lee Boyle, former historian for the National Park Service at Valley Forge National Historical Park, who compiled quotes from primary sources documenting the food situation there during 1777 and 1778, mostly from the National Archives.

Nancy Carter of North Wind Picture Archives, who has helped me illustrate various book projects for nearly two decades.

Emily DeWitt-Cisneros, my niece, who proved to be an excellent research assistant while working on her first book project.

Google Books, the single greatest history research tool of the last decade.

Gwyneth Doland, who made excellent suggestions about the development of this project.

Barbara Kerr, of the Medford (Massachusetts) Historical Society, who uncovered some obscure details about the history of rum and Paul Revere for me and who urged me to consult the research miracle of Google Books.

Peter Lynch, my second editor at Sourcebooks.

Dona McDermott, archivist at Valley Forge National Historical Park.

Scott Mendel, my agent with the Mendel Media Group, who has managed to find a home for all of my book projects that have made it into proposal form.

Wayne Scheiner, my closest friend for thirty-five years, who first suggested that I examine the culinary legacy of Thomas Jefferson.

Mary Scott-Fleming of Monticello and the Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

Mary Jane Wilan, my wife, who knows that each manuscript that I turn in to a publisher results in a nice trip overseas to celebrate.

Introduction

FOODIES AND POLYMATHS

Few scholars are cooksand fewer cooks scholars. Perhaps this accounts for the fact that no other aspect of human endeavor has been so neglected by historians as home cooking.

FOOD HISTORIAN KAREN HESS IN MARTHA WASHINGTONS BOOKE OF COOKERY, 1981

I n April 1962, two months before I graduated from James Madison High School in Vienna, Virginia, President John F. Kennedy, at a dinner honoring Nobel Prize winners of the Western Hemisphere, paid homage to Thomas Jeffersons wide-ranging interests and talents when he remarked, I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone. Five months later, I was enrolled at Mr. Jeffersons Academical Village, the University of Virginia, and was living in Echols Hall as an Echols Scholar.

To say that Jefferson wasand still isworshipped at the university is an understatement. His legacy lingers everywhere, from the serpentine walls he designed for the gardens to the buildings he modeled after Greco-Roman structures and the statues of him and of George Washington opposite each other on the lawn. The story went that, if a virginal woman passed between the two statues, Mr. Washington would bow to Mr. Jefferson.

It was a tradition that we wore coats and ties to class. We were not required to do this, of course, but everyone dressed up because we were Virginia gentlemen (we even drank that brand of bourbon!). Our uniform was a blue blazer, khaki slacks, a light-blue button-down shirt (Gant, of course), a rep tie in the universitys colors of orange and navy blue, and Weejun penny loafers with no socks in warm weather. One morning during my first year, on the way to take an exam that I had studied most of the night for, I was crossing the lawn when I passed Dr. Edgar F. Shannon, the president of the university. I was mortified because that morning I had skipped the tie, but Dr. Shannon made no mention of it. He merely said, Good morning, David. Unbelievablehe had remembered my name after a single meeting months earlier at an Echols Scholar orientation party.

My education at the universityI majored in English and took creative writing coursesultimately led to my writing career, but not before a radical change in focus. No longer would I specialize in animal symbolism in the novels of James Joyce, my masters thesis title; I would study and write about my first loves, food history and cooking.

Jefferson became my most significant hero. After I graduated from the university in 1966, I knew from the history I had absorbed that Thomas Jefferson was the ultimate multitalented and multidimensional historical figure. But I didnt know about his love of food and wine until many years later, when I began to read more history, especially more food history. Jeffersons name appeared time and time again in the history of wine, horticulture, and food importation. While working on Da Vincis Kitchen, I consulted Silvano Serventi and Franoise Sabbans Pasta: The Story of a Universal Food and discovered that Jefferson was widely credited with being the first American to import pasta into the new United States. It wasnt precisely true, but that did itI was hooked.

During my subsequent research, I realized that the story of early American food and wine was not just about Jefferson but also included Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and many obscure but brilliant individuals who became my founding foodies. I decided that this was a food history that had to be written, but there were obstacles. The first and most important challenge was the lingering reputation of colonial-era foodit was not good at all, according to most accounts.

But in 1977, food historians John Hess and Karen Hess wrote this in The Taste of America: Thus, in this bicentennial period, such quasi-official historians as Daniel J. Boorstin and James Beard assure us that we have never had it so goodthat Colonial Americans were primitives and ignoramuses in matters gastronomic. The truth is almost precisely to the contrary. The Founding Fathers were as far superior to our present political leaders in the quality of their food as they were in the quality of their prose and of their intelligence. My research proves that the Hess theory is true, and what Ive learned has opened a window into the past culinary triumphs of those founding foodies.

Next page