Contents

Guide

Page List

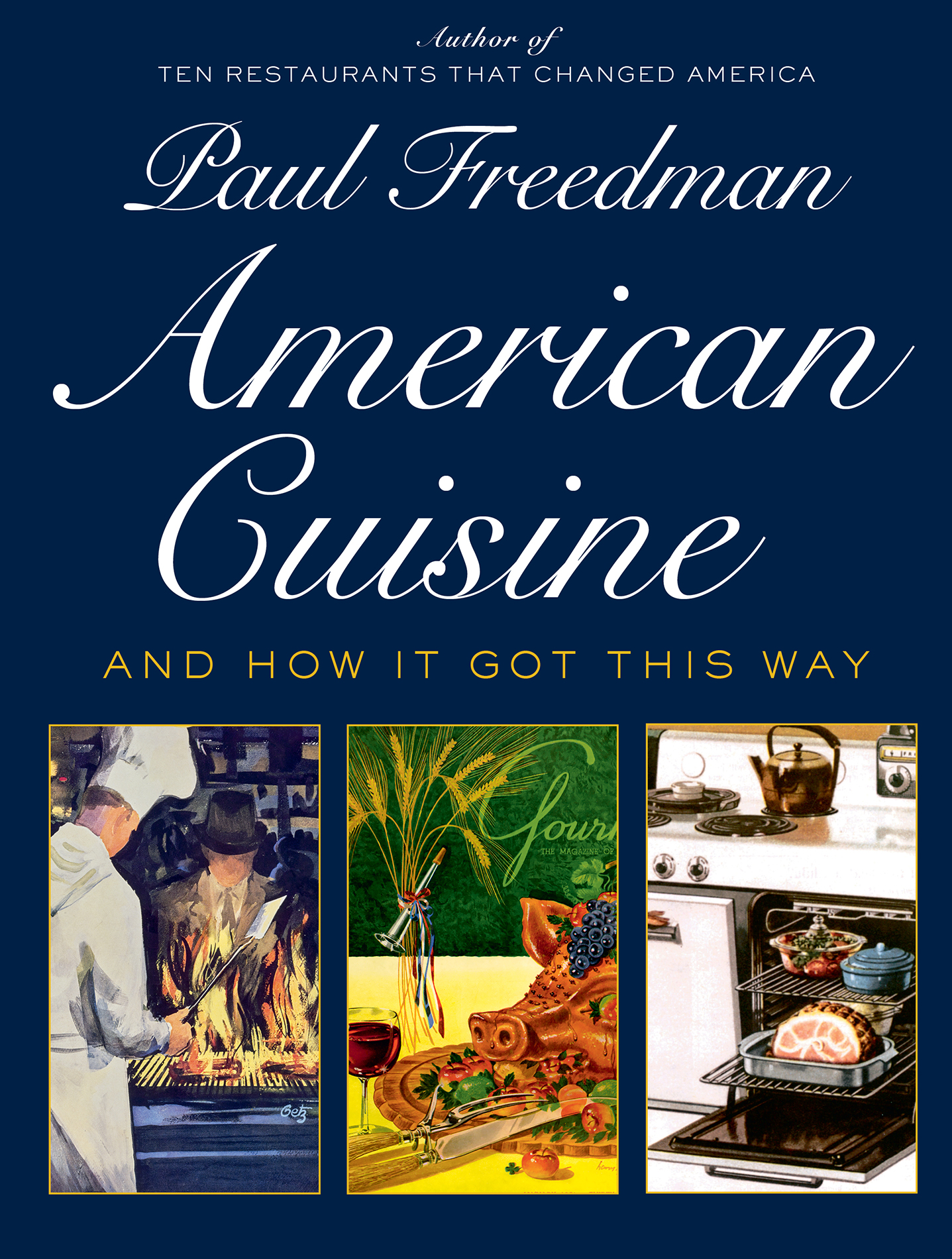

ALSO BY PAUL FREEDMAN

Ten Restaurants That Changed America

Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination

Food: The History of Taste (editor)

Images of the Medieval Peasant

American Cuisine

AND HOW IT GOT THIS WAY

PAUL FREEDMAN

For Bonnie. Weve had some nice meals...

Contents

E ven in the twenty-first century, many people think that American cuisine does not exist. In contrast to other nations, the United States does not have a clear culinary dossier; what Americans eat reflects eclecticism and experimentation, not obedience to tradition or rules. Why not have guacamole or blue cheese with that burger, or maybe try some pineapple on that pizza? The consumer has many choices, from restaurant types (Chinese, Mexican, diner) to ice cream flavors, but only in recent years have people paid attention to quality as opposed to variety. What Alice Waters, the founder of Berkeleys Chez Panisse restaurant, termed the delicious revolution restored attention to primary products. This simple but truly revolutionary notion inspires todays farm-to-table cuisine. Rather than How many things can I make with canned peaches, the question is Where can I find a juicy, fresh peach? Since the 1970s, there has been a stunning upsurge of attention to dining as pleasurable, so food is now a major subject of conversation and media attention. What follows, then, in American Cuisine: And How It Got This Way is a narrative discussing the recent innovations, but in order to understand our current cuisine, it is vital to look at what came before and how American food took the form it now has.

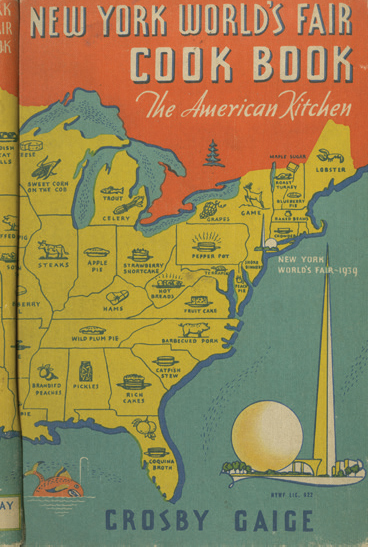

The anthropologist Sidney Mintz, one of the founding fathers of the serious study of food in history, once defined a cuisine as a cultural phenomenon that ordinary people discuss and about which they have strong opinions. He went on to say that in the absence of such an intense culinary culture, America doesnt have a cuisine. Reproachful responses to this statement focused on the regional glories of the United States: What about our marvelous Western game, Pennsylvania sausage, Chesapeake Bay terrapin, and so forth? Deprecation of American cuisine was answered by pointing to the food of its regions, an assertion that would be repeated throughout the next century.

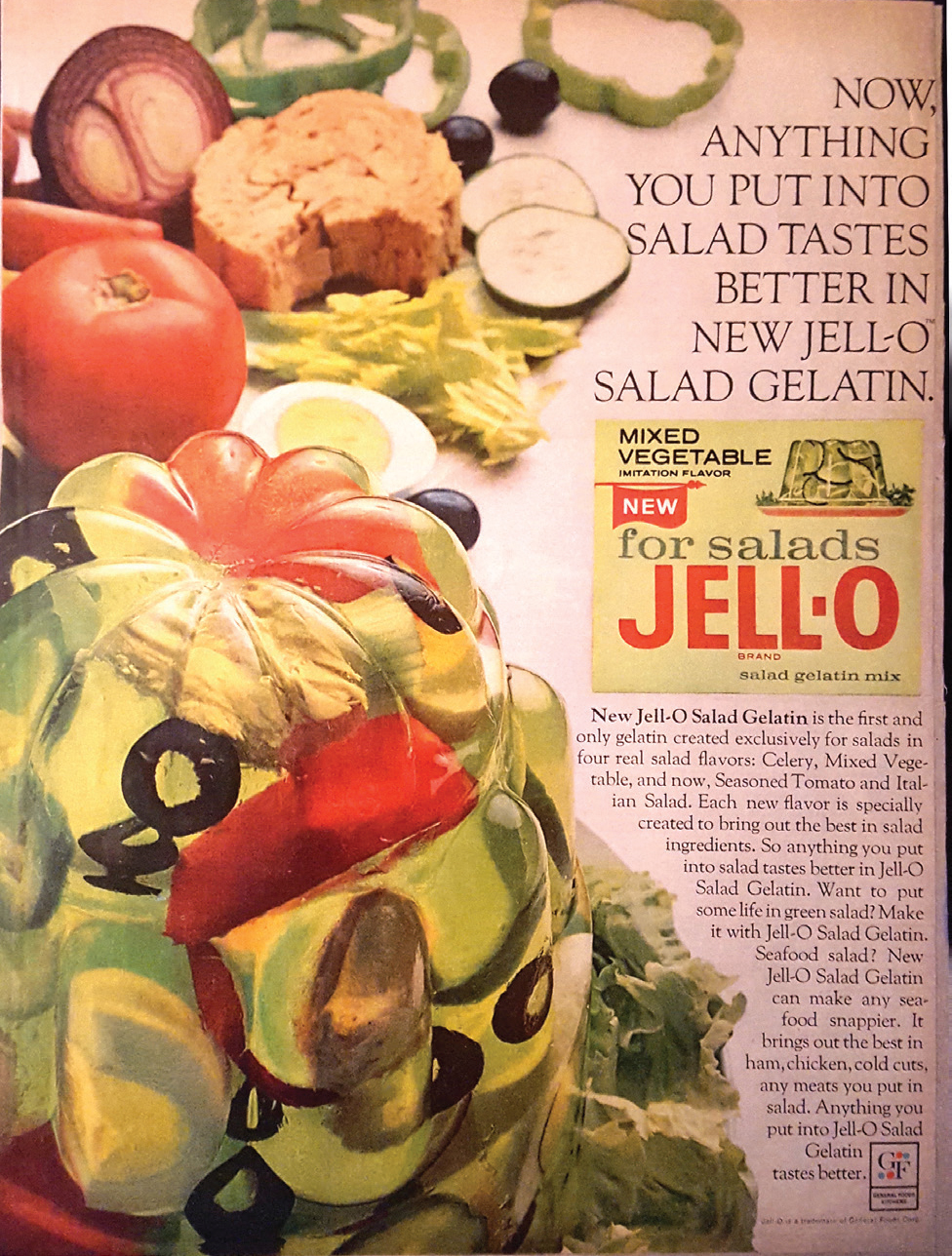

Jell-O mixed vegetable flavor. From Better Homes and Gardens, 1965. Jell-O salad was usually made with lime or lemon Jell-O or unflavored gelatin, but this line of vegetable flavors was a feature of the 1960s.

Foreign observers often assume, contemptuously, that people in the United States live exclusively on fast foodMcDonalds is really what American cuisine amounts to. Allied to this is the common notion that Americans dont actually enjoy food, at least not in a thoughtful, leisurely way. As far back as the early nineteenth century, European travelers were appalled at how quickly Americans wolfed down their food: ten minutes for breakfast and twenty for other meals, according to one haughty British visitor in 1820. The pleasures of conversation while dining seemed to be unknown to Americans, who regarded eating as a task best accomplished as fast as possible.

In a classic essay entitled An American Tragedy, written in 1930, the food writer and wine merchant Andr Simon identified three false gods of American dining: speed, sugar, and shows (e.g., singing waiters, dancing, and other distractions). He sadly observed that bolting ones food [is] a crazy habit which ruins the health of millions of people, people who have no idea of what to do with the spare time on their hands and yet swallow a few sandwiches for lunch in five minutes instead of enjoying a proper meal in a rational manner.

It seems unfairEuropeans denounce the United States for large portions and chronic overeating on the one hand and, on the other, claim Americans give no thought to the pleasures of dining. Unfortunately, haste and overeating are related, and both remain national traits even in this present era of food fascination. Some of this has to do with the food industry itself, which does better at providing low prices and convenience than high quality. Oversize restaurant portions are linked to the relatively low cost of food compared to other expenses such as rent, labor, and insurance. The restaurant needs to justify pricing at a certain level and is willing to throw in more food in order to charge a profitable amount. Another structural inducement to overeating is the snack food category. Snacking increases total food sales, and more money is made off barbecue-flavor potato chips than raw potatoes or even mashed potato mix. Advertising therefore encourages grazing.

As for Americans not liking food, there is a real variation in how seriously different nations regard dining, if not food itself. The French diplomat and bon vivant Prince Talleyrand said, Show me another pleasure like dinner which comes every day and lasts an hour.

Beyond love of fast food or eating in a hurry, Americans and their dining options now actually have some favorable images abroad, but this is new, almost unprecedented. Where our eclecticism was once evidence of a lack of culinary standards, the United States is now recognized as impressive, awesome even, for the variety of its ethnic food offerings. American culinary internationalism takes two forms. One is regional influence of immigration, such as German cuisine in Pennsylvania or Mexican in California. Second is the phenomenon of diverse restaurants reflecting many nations, which has extended to food trucks and multinational food courts. Such restaurant options used to be associated with large, polyglot cities like New York or Chicago, but the phenomenon is now everywhere. At one time, Europeans in particular regarded the prominence of foreign restaurants as proof that there is no true American cuisine, but now such places are tourist attractions and imitated abroad. It still doesnt get us very far, however, in identifying common food characteristics across the United States other than diversity itself.

Americans have always been reluctant to accept the common foreign attitude that there are no canonical American dishes. The quest for a core culinary experience began over two hundred years ago with a cookbook entitled American Cookery, which appeared in 1796. Its author, Amelia Simmons, identified simply and mysteriously as an American Orphan, was the first to claim to be publishing a work presenting the cuisine of the newly independent nation. The book is certainly original, but it does not come close to laying out a distinctive cuisine.