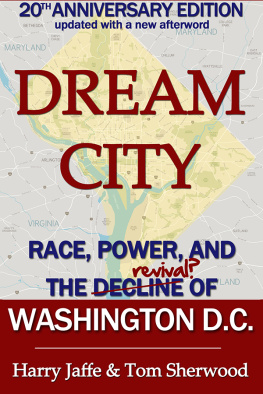

Copyright 1994, 2014 by Harry S. Jaffe and Tom Sherwood

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used, reproduced, downloaded, scanned, stored, or distributed in any stored in any form or manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the authors. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

For information, address Harry S. Jaffe and Tom Sherwood c/o David Black Agency, 335 Adams Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201.

My friend and colleague Chuck Conconi once told me that writing a book is like walking through a room full of mashed potatoes. He's right. And most days one of my three daughters would wade in and ask: "Is the book done yet?"

David Black, our literary agent, did everything but write the book. He coaxed and cajoled us through the early stages. He became my coach, my therapist, my punching bag, and through it all, my friend, who said long before I believed him that I could write a book. If not for his patience and deft negotiations, the book would have stayed in manuscript form.

I needed many editors. Brian Kelly, my editor at large, helped at the conceptual stage and kept me on course during long diner lunches and squash matches. Jane Leavy was our most careful reader. She made me reach deeper into myself and the material, and like the best editors, made it better. Gerri Hirshey read and said what I needed to hear, when I needed to hear it. Marc Jaffe gave "strength to my elbow" and provided a crucial mid-course correction. Barbara Marcus cut the fat with a scalpel. We're also indebted to Paul Aron at Prentice-Hall Press for recognizing the value of our book and taking it through the early stages; and to Dominick Aufuso and Cassie Jones at Simon & Schuster for their patience and commitment in seeing it through to the end.

The reporting for this book began years ago while I was writing for Regardie's, the gutsy monthly magazine that flourished in the eighties. Bill Regardie was the best publisher imaginable. He gave me the time and the space to develop an understanding of the "money, power, and greed" that make Washington tick. At Washingtonian, I want to thank Jack Limpert, my editor, and publishers Philip and Eleanor Merrill for their forbearance during the actual writing. Mark Plotkin introduced me to city politics, as he reminds me all the time.

Tom and I owe a great debt to all our sources. Hundreds of people were willing to share their recollections, insights, and emotions, even though many of the events were painful and unpleasant to recall. My special thanks to Al Arrington, Carol Thompson Cole, and Carroll Harvey for their generosity in time and spirit.

Finally, I want to acknowledge my friend John Wilson, who was perhaps my deepest and most constant source. He was there during many of the events that we describe. He knew the characters and gave us the unvarnished truth about them. I only wish that he were here to read it and tell us everything that we missed.

Harry S. Jaffe

First, I want to acknowledge someone I don't know. A few years ago, a burly man sat next to my son and me in Florida during a spring-training baseball game between the Boston Red Sox and the Baltimore Orioles. The man turned to me and said derisively, "Oh, you're from Washington. You must either work for the government or be on welfare."

Such bigotry stung, and inspired me to tell the country more about the nation's capital.

For this project, I thank Harry Jaffe for proposing a book on Washington and seeing the value of my work as a journalist with ties to the city's diverse black communities. And my appreciation to Harry's wife, Cindy Morgan Jaffe, whose empathetic support was matched by her counsel on substance.

Thanks to my son, Peyton. Even as I am having my first book published, he's getting his first driver's license. Both make me very nervous, but my son unfailingly makes me proud. And to Deborah Jones Sherwood, his mother, for being such a good one and for encouraging me early on to reach further than I could see.

I'm grateful to sustaining friends Nancy Lewis and Gene Bachinski, superior journalists both, who, while they taught me the value of fine food and wine (they feed me a lot), offer me the warmth of unyielding loyalty. To Bob Galano and Terry Dale, for true friendship and frequent refuge from a weary land. And to Phyllis Jones, passionate and committed, with unusual understanding of local Washington and its racial complexity.

A posthumous debt of gratitude to Herbert Denton, Washington Post city editor, who encouraged my initial interest in hometown Washington, and to Post editor Milton Coleman, whose support and enthusiasm allowed me the opportunity to write so much about it.

My thanks to the many good District government workers who each day try to do a difficult job made even more difficult by decades of poor management. And, finally, an acknowledgment of debt and appreciation to the tens of thousands of black middle-class Washingtonians who are not featured in this bookthe individuals and families who do not make the news but each ordinary day make their homes, businesses, and communities places of pride and decency. They deserve so much more recognition, appreciation, and help than their governmentor the mediais likely ever to give them.

Tom Sherwood

In memory of my father, Josef, who taught me to love books.

And for my mother, Zelda, who believes in me.

Harry S. Jaffe

For my son, Peyton, who once innocently illuminated all the time spent on this project by tellinga caller, Hes not here; hes working on that damn book.

Tom Sherwood

to the 20th Anniversary Edition

When Kaya Henderson, the District's school chancellor, moved into her home in the Brookland neighborhood in 2001, her street of tidy row homes was solidly African American. The Northeast section of the nation's capital off South Dakota Avenue near Providence Hospital had been home to DC's black middle class for decades.

"That's not the case any longer," Henderson told us one fall afternoon in 2013. She stood on her porch and looked across the street. "White families have moved into those houses. Some have children, and the kids are starting to play together. It's a good thing, but I can't say there isn't some tension."

Henderson's neighborhood was hardly unique. It was the new normal across Washington, D.C. Reflecting demographic changes taking place nationwide, younger people were moving into the city, most were white and quite a few hoped to raise families in neighborhoods that had been largely African American.

Since Dream City was published in 1994, the city behind the monuments had transformed itself. From politics to society, demographics to development, sports to culinary culture, the District of Columbia barely resembled the town we described twenty years ago. Except for one constant: Marion Barry was still in office, representing Ward 8 on the D.C. council.

When we put the last period on the print edition, Sharon Pratt Kelly was finishing her term as mayor, which most saw as a failure. Marion Barry had served six months in jail for a cocaine conviction and had won a seat representing Ward 8 on the council. He was contemplating a run for mayor.