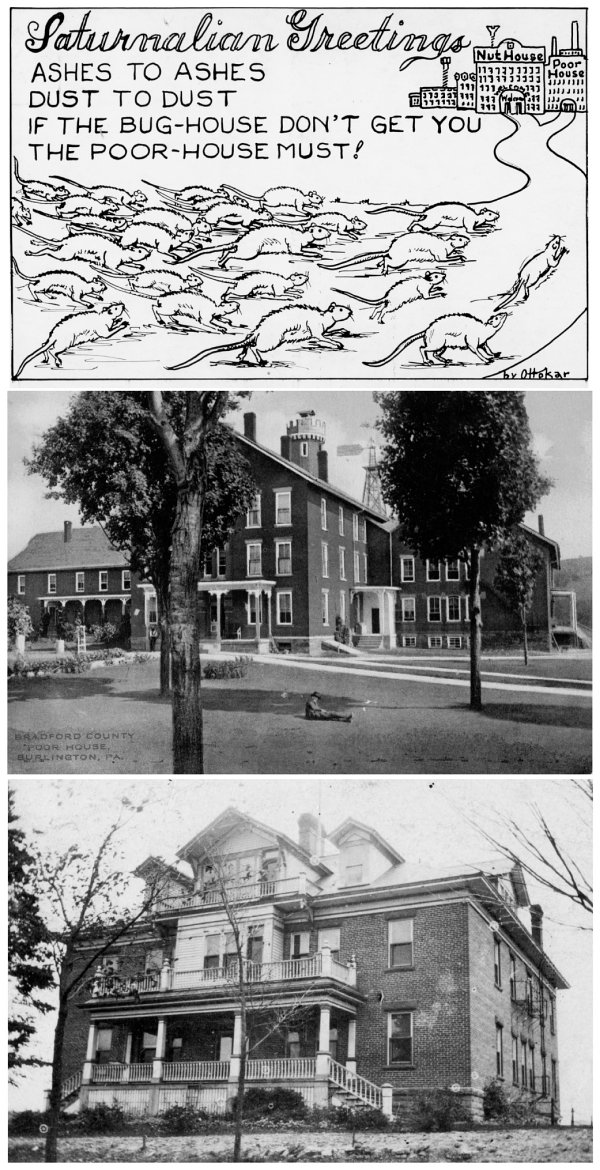

Poorhouses were common enough that they often appeared in offensive, idealized, or ominous early-twentieth-century postcards.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Sophie

Fifty percent of the royalties from this book will be donated to the Juvenile Court Project of Pittsburgh, Indiana Legal Services of Indianapolis, and the Los Angeles Community Action Network (LA CAN).

In October 2015, a week after I started writing this book, my kind and brilliant partner of 13 years, Jason, got jumped by four guys while walking home from the corner store on our block in Troy, New York. He remembers someone asking him for a cigarette before he was hit the first time. He recalls just flashes after that: waking up on a folding chair in the bodega, the proprietor telling him to hold on, police officers asking questions, a jagged moment of light and sound during the ambulance ride.

Its probably good that he doesnt remember. His attackers broke his jaw in half a dozen places, both his eye sockets, and one of his cheekbones before making off with the $35 he had in his wallet. By the time he got out of the hospital, his head looked like a misshapen, rotten pumpkin. We had to wait two weeks for the swelling to go down enough for facial reconstruction surgery. On October 23, a plastic surgeon spent six hours repairing the damage, rebuilding Jasons skull with titanium plates and tiny bone screws, and wiring his jaw shut.

We marveled that Jasons eyesight and hearing hadnt been damaged. He was in a lot of pain but relatively good spirits. He lost only one tooth. Our community rallied around us, delivering an almost constant stream of soup and smoothies to our door. Friends planned a fundraiser to help with insurance co-pays, lost wages, and the other unexpected expenses of trauma and healing. Despite the horror and fear of those first few weeks, we felt lucky.

Then, a few days after his surgery, I went to the drugstore to pick up his painkillers. The pharmacist informed me that the prescription had been canceled. Their system showed that we did not have health insurance.

In a panic, I called our insurance provider. After navigating through their voice-mail system and waiting on hold, I reached a customer service representative. I explained that our prescription coverage had been denied. Friendly and concerned, she said that the computer system didnt have a start date for our coverage. Thats strange, I replied, because the claims for Jasons trip to the emergency room had been paid. We must have had a start date at that point. What had happened to our coverage since?

She assured me that it was just a mistake, a technical glitch. She did some back-end database magic and reinstated our prescription coverage. I picked up Jasons pain meds later that day. But the disappearance of our policy weighed heavily on my mind. We had received insurance cards in September. The insurance company paid the emergency room doctors and the radiologist for services rendered on October 8. How could we be missing a start date?

I looked up our claims history on the insurance companys website, stomach twisting. Our claims before October 16 had been paid. But all the charges for the surgery a week latermore than $62,000had been denied. I called my insurance company again. I navigated the voice-mail system and waited on hold. This time I was not just panicked; I was angry. The customer service representative kept repeating that the system said our insurance had not yet started, so we were not covered. Any claims received while we lacked coverage would be denied.

I developed a sinking feeling as I thought it through. I had started a new job just days before the attack; we switched insurance providers. Jason and I arent married; he is insured as my domestic partner. We had the new insurance for a week and then submitted tens of thousands of dollars worth of claims. It was possible that the missing start date was the result of an errant keystroke in a call center. But my instinct was that an algorithm had singled us out for a fraud investigation, and the insurance company had suspended our benefits until their inquiry was complete. My family had been red-flagged.

* * *

Since the dawn of the digital age, decision-making in finance, employment, politics, health, and human services has undergone revolutionary change. Forty years ago, nearly all of the major decisions that shape our liveswhether or not we are offered employment, a mortgage, insurance, credit, or a government servicewere made by human beings. They often used actuarial processes that made them think more like computers than people, but human discretion still ruled the day. Today, we have ceded much of that decision-making power to sophisticated machines. Automated eligibility systems, ranking algorithms, and predictive risk models control which neighborhoods get policed, which families attain needed resources, who is short-listed for employment, and who is investigated for fraud.

Health-care fraud is a real problem. According to the FBI, it costs employers, policy holders, and taxpayers nearly $30 billion a year, though the great majority of it is committed by providers, not consumers. I dont fault insurance companies for using the tools at their disposal to identify fraudulent claims, or even for trying to predict them. But the human impacts of red-flagging, especially when it leads to the loss of crucial life-saving services, can be catastrophic. Being cut off from health insurance at a time when you feel most vulnerable, when someone you love is in debilitating pain, leaves you feeling cornered and desperate.

As I battled the insurance company, I also cared for Jason, whose eyes were swollen shut and whose reconstructed jaw and eye sockets burned with pain. I crushed his pillspainkiller, antibiotic, anti-anxiety medicationsand mixed them into his smoothies. I helped him to the bathroom. I found the clothes he was wearing the night of the attack and steeled myself to go through his blood-caked pockets. I comforted him when he awoke with flashbacks. With equal measures of gratitude and exhaustion, I managed the outpouring of support from our friends and family.

I called the customer service number again and again. I asked to speak to supervisors, but call center workers told me that only my employer could speak to their bosses. When I finally reached out to the human resources staff at my job for help, they snapped into action. Within days, our insurance coverage had been reinstated. It was an enormous relief, and we were able to keep follow-up medical appointments and schedule therapy without fear of bankruptcy. But the claims that had gone through during the month we mysteriously lacked coverage were still denied. I had to tackle correcting them, laboriously, one by one. Many of the bills went into collections. Each dreadful pink envelope we received meant I had to start the process all over again: call the doctor, the insurance company, the collections agency. Correcting the consequences of a single missing date took a year.

Ill never know if my familys battle with the insurance company was the unlucky result of human error. But there is good reason to believe that we were targeted for investigation by an algorithm that detects health-care fraud. We presented some of the most common indicators of medical malfeasance: our claims were incurred shortly after the inception of a new policy; many were filed for services rendered late at night; Jasons prescriptions included controlled substances, such as the oxycodone that helped him manage his pain; we were in an untraditional relationship that could call his status as my dependent into question.

Next page