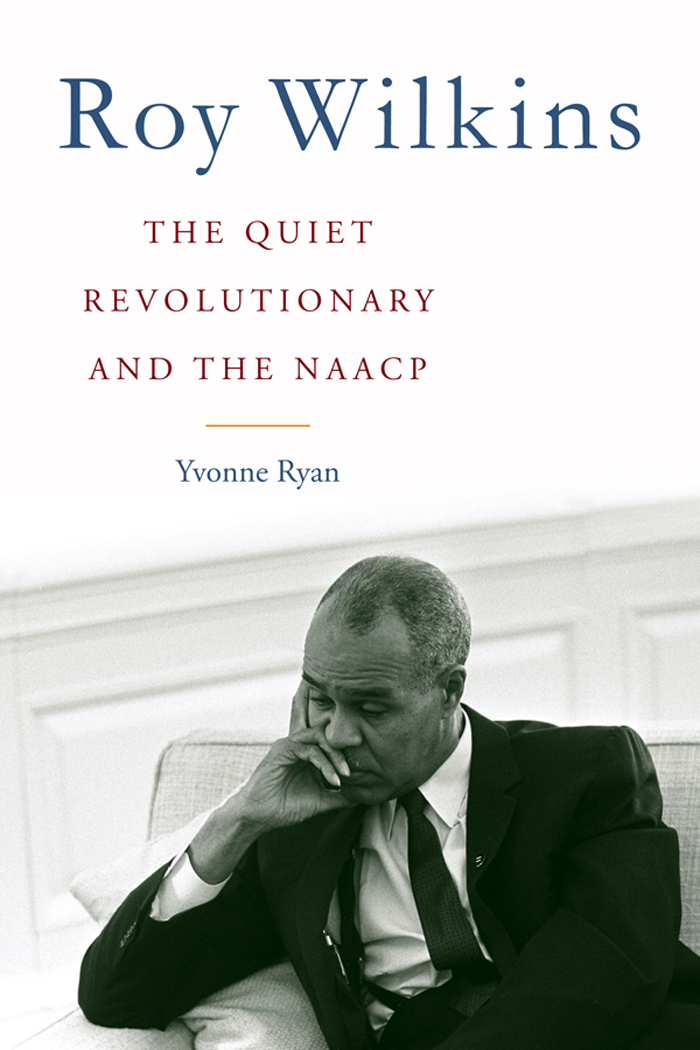

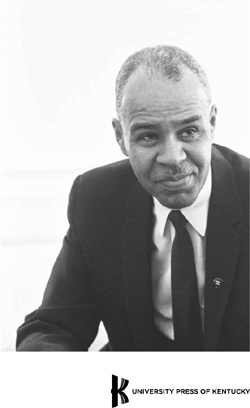

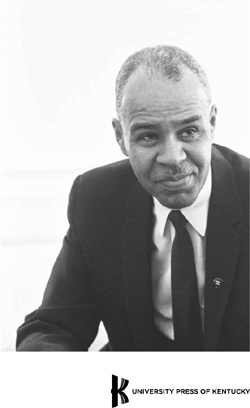

Roy Wilkins

Roy Wilkins

The Quiet Revolutionary and the NAACP

YVONNE RYAN

Copyright 2014 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern

Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky

Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray

State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University

of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Frontispiece: Roy Wilkins (LBJ Library; photo by Yoichi Okamoto)

17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ryan, Yvonne, 1961

Roy Wilkins : the quiet revolutionary and the NAACP / Yvonne Ryan.

pages cm. (Civil rights and the struggle for black equality in the twentieth century)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8131-4379-8 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8131-4381-1 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-8131-4380-4 (epub)

1. Wilkins, Roy, 1901-1981. 2. Civil rights movementsUnited StatesHistory

20th century. 3. African AmericansCivil rightsHistory20th century.

4. National Association for the Advancement of Colored PeopleBiography.

5. Civil rights workersUnited StatesBiography. 6. African American civil rights

workersBiography. I. Title.

E185.97.W69R93 2013

323.092dc23

[B] 2013029396

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Contents

Introduction

On the morning of September 10, 1981, flags on all government buildings in the United States flew at half-mast to mark the death of Roy Wilkins, former leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the countrys oldest and largest civil rights organization. At Wilkinss funeral the following day, Vice President George Bush and Senator Ted Kennedy joined nine hundred mourners to listen to eulogies from veterans of the civil rights movement, for whom Wilkinss passing represented the end of a momentous chapter in the movements history. His death had been reported in the nations newspapers, whose editorials paid tribute to his achievements and his cool, solid leadership. But even as soprano Leontyne Price sang We Shall Overcome over his coffin, Wilkins was fading from the public consciousness, his achievements and contributions to a crucial period in American history nearly forgotten.

Many of Wilkinss colleagues and peers, including Thurgood Marshall, the NAACPs flamboyant and charismatic general counsel, and Walter White, Wilkinss predecessor, have been the subject of scholarly attention; but Wilkinss contribution to the civil rights movement has so far been ignored in the scholarly examinations of this important period. Wilkins lacked the oratorical skills that could lift an audience, in part because he appeared to lack the passion to paint a vision of freedom. Instead, he often appeared aloof, patrician, and urbane: more like a sophisticated chief executive of a multinational corporation than of an organization dedicated to righting a set of fundamental injustices.

Wilkins spent forty-six years of his life within the NAACP, retiring just four years before his death. Yet despite his position as head of the organization, which he led from 1955 to 1977, he remains an enigma. His position put him at the center of many of the most important events of the civil rights movement, but he features in the movements historiography only in the context of other players. Most, if not all, significant histories of the movement mention him, but he appears almost as a supporting actor, whose presence mainly serves as a counterpoint to the more interesting players. He is seen, at best, as a paternalistic uncle; more often he is viewed as an aging, difficult, and hierarchical bureaucrat who held his organization back, allowing younger, more exciting groups to take the glory and garlands.

Wilkins was born in 1901, five years after the Supreme Court had enshrined the legal precedent for the separation of the races that, by the time of Wilkinss birth, extended to almost every area of public life. He grew up in St. Paul, Minnesota, among white immigrants from all corners of Europe, and from the age of five attended an integrated school. He felt deeply that black Americans should enjoy the same economic and social opportunities as their white counterpartshis writings and speeches are testament to thatbut his approach was almost academic. For Wilkins, desegregation and discrimination were irrational concepts; as a result he often took a detached, intellectual approach to the fight for equality. This detachment should not be confused with disinterest or lack of anger. His career provides many examples of his rage at yet another unjust act, his anger usually expressed through his newspaper columns or his speeches. However, Wilkins invariably looked toward a legislative remedy as the ultimate solution. He abhorred the use of violence as a response to injustice, even while he acknowledged the occasional necessity for armed self-defense. The only rational and effective way to address inequality, as far as Wilkins was concerned, was to ensure that rights were protected through legislation and court rulings. His detachment allowed him to serve as the conduit between civil rights activists demonstrating on the streets of Selma, for example, and the white power structure. He shared with President Lyndon Johnson and the NAACPs Washington lobbyist, Clarence Mitchell, an understanding of the complexity of the legislative process and was particularly adept at negotiating and navigating the corridors of power.

His absence from histories of the civil rights movement is particularly puzzling because Wilkins in fact led two powerful civil rights organizations. In addition to his position as secretary of the NAACP, he led the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR), a coalition of religious, fraternal, civil, and labor groups founded in 1950 by Wilkins, A. Philip Randolph, the leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters railway union, and Arnold Aronson, a leader of the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council. The LCCR was set up to coordinate various advocacy groups in lobbying Congress and, through their efforts, the organization supported the passage of the landmark civil and voting rights legislation of 1957, 1964, 1965, and 1968. One of the reasons why Wilkins was reluctant to embrace direct action as a primary tactic of the NAACP was that he believed black Americans did not constitute a powerful enough group in the United States to force widespread social and economic change; he argued, for example, that boycotts worked best in communities where African Americans carried significant economic weight but could not be applied effectively in every town or city. Joining forces with the groups affiliated with the LCCR gave the NAACP the ballast it needed to demand congressional action.