Though Columbus denied to his dying day having discovered a continent previously unknown to Europeans, geographers thought otherwise and named the new lands after Amerigo Vespucci, an Italian member of a Portuguese expedition to South America whose widely reprinted report suggested a new world had been found.

Excited by the gold Columbus had brought back from America, Ferdinand and Isabella, joint monarchs of Spain, sought formal confirmation of their ownership of these new lands. They feared the interference of Portugal, which was at that time a powerful seafaring nation and had been active in overseas exploration. At Spains urging the pope drew a Line of Demarcation one hundred leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands, dividing the heathen world into two equal parts that east of the line for Portugal and that west of it for Spain.

Because this line tended to be unduly favorable to Spain, and because Portugal had the stronger navy, the two countries worked out the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), by which the line was moved farther west. As a result, Brazil eventually became a Portuguese colony, while Spain maintained claims to the rest of the Americas. As other European nations joined the hunt for colonies, they tended to ignore the Treaty of Tordesillas.

1.2 THE SPANISH CONQUISTADORES

To conquer the Americas the Spanish monarchs used their powerful army, led by independent Spanish adventurers known as conquistadores, who sought to win glory and wealth and spread the Roman Catholic faith, and were not squeamish about the means they used to do so.

At first the conquistadores confined their attentions to the Caribbean islands, where the European diseases they unwittingly carried with them devastated the local Indian populations, who had no immunities against such diseases.

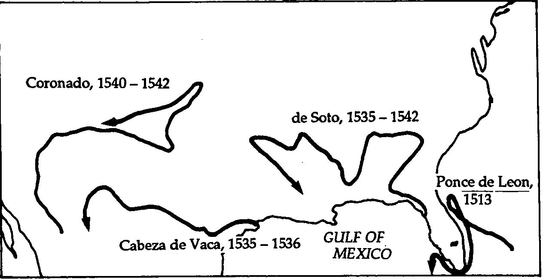

After about 1510 the conquistadores turned their attention to the American mainland. In 1513 Vasco Nuez de Balboa crossed the isthmus of Panama and became the first European to see the Pacific Ocean, which he claimed for Spain. The same year Juan Ponce de Leon explored Florida in search of gold and a fabled fountain of youth. He found neither but claimed Florida for Spain.

In 1519 Hernando (Hernan) Cortes led his dramatic expedition against the Aztecs of Mexico. Aided by the fact that the Indians at first mistook him for a god, as well as by firearms, armor, horses, and (unknown to him) smallpox germs, all previously unknown in America, Cortes destroyed the Aztec empire and won enormous riches.

Other conquistadores endeavored to follow Cortes example, sometimes with similar results. By the 1550s such fortune seekers had conquered much of South America.

In North America the Spaniards sought in vain for riches. In 1528 Panfilio de Narvaez led a disastrous expedition through the Gulf Coast region from which only four of the original four hundred men returned. One of them, Cabeza de Vaca, brought with him a story of seven great cities full of gold (the Seven Cities of Cibola) somewhere to the north. In response to this, two Spanish expeditions explored the interior of North America:

- Hernando de Soto led a six hundred-man expedition (1539 1541) through what is now the southeastern United States, penetrating as far west as Oklahoma and discovering the Mississippi River, on whose banks de Soto was buried.

- Francisco Vasquez de Coronado led an expedition (1540 1542) from Mexico, north across the Rio Grande and through New Mexico, Arizona, Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. Some of Coronados men were the first Europeans to see the Grand Canyon.

While neither expedition discovered rich Indian civilizations to plunder, both increased Europes knowledge of the interior of North America and asserted Spains territorial claims to the continent.

1.3 NEW SPAIN

Spain administered its new holdings as an autocratic, rigidly controlled empire in which everything was to benefit the parent country. Tight control of even mundane matters was carried out by a suffocating bureaucracy run directly from Madrid. Annual treasure fleets carried the riches of the New World to Spain for the furtherance of its military-political goals in Europe.

As population pressures were low in sixteenth-century Spain, only about 200,000 Spaniards came to America during that time. To deal with the consequent labor shortages and as a reward to successful conquistadores the Spaniards developed a system of large manors or estates ( encomiendas ) with Indian slaves ruthlessly managed for the benefit of the conquistadores. The encomienda system was later replaced by the similar but somewhat milder hacienda system. As the Indian population died from overwork and European diseases, Spaniards began importing African slaves to supply their labor needs. Society in New Spain was rigidly stratified, with the highest level reserved for natives of Spain ( peninsulares ) and the next for those of Spanish parentage born in the New World ( creoles ) . Those of mixed or Indian blood occupied lower levels.

After 1535 New Spain was ruled by a viceroy, a Spanish nobleman appointed by the king to act as his representative in the colonies.