1.1 Aboriginal Peoples

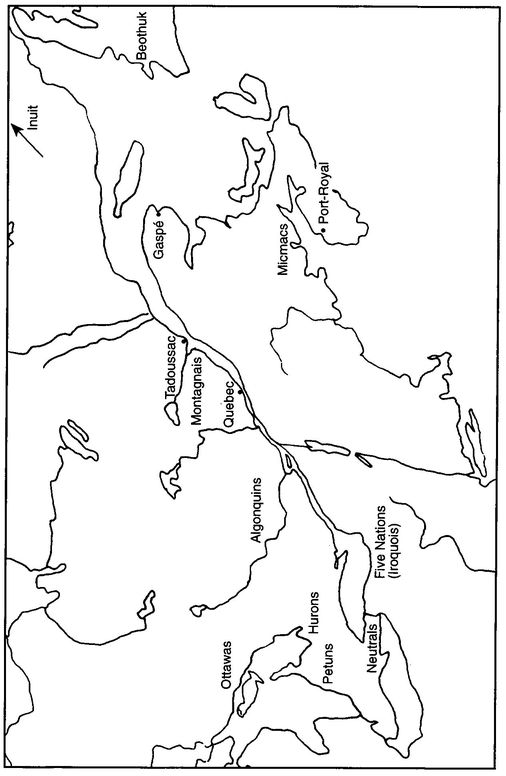

Our knowledge of Canada prior to the arrival of the first Europeans is fragmented and open to contention. The generally accepted theory holds that North Americas aboriginal peoples migrated from Asia across the Bering Strait. While the timing of these migrations is disputed, humans were present in the Americas between 15 000 and 10 000 B.C. They were a rich diversity of peoples whose lifestyles varied with each locality. They migrated within the continent. Inuit, for instance, occupied part of the north shore of the St. Lawrence River until driven farther north by Montagnais Indians, who called them Eskimo (eaters of raw meat).

While the number of aboriginal peoples north of Mexico at the time of the Europeans arrival has been estimated at 10 million, those in what is now Canada varied between a half million and two and a half million. Amer-Indians have been classified according to linguistic, tribal, and cultural traits, such as are described in the following.

The first Indians that Europeans met were the Eastern Woodland Indians. Basically, they are divided into two groupings, the Algonkian (or Algonquin) and Iroquoian speaking peoples. Algonkians such as the Beothuk in Newfoundland (who became extinct in the nineteenth century) and the Micmacs of the Maritimes, the Maliseets (Malecites) of New Brunswick, and the Montagnais, Ottawas, and Algonquins of central Canada were foragers who lived in small bands of 20 to 100 people and hunted and fished.

Settlements Among Aboriginal Peoples

Iroquoian speaking peoples lived further inland and engaged in slash and burn agriculture. They included two important confederacies: the Huron, consisting of the Bear, Rock, Cord, and Deer peoples in the area between Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay in Ontario; and the Iroquois or Five Nations, Six Nations after they were joined by the Tuscaroras in the early eighteenth centurythe Mohawks, Senecas, Oneidas, Onondagas, and Cayuga, living principally south of Lake Ontario. The Petun, Erie, and Neutral nations in southwestern Ontario were other Iroquoians. This linguistic grouping of people lived in longhouses, containing 20 to 30 families, and settled in villages that moved every decade or so in search of fertile ground in which to grow maize and other vegetable crops.

Peoples living in the West and on the West coast had a different manner of food-gathering. Peoples living on the Plains used horses to hunt bison (buffalo), while others living in woodlands and parklands obtained food through different means. The Crees, who were Algonkian speakers, and Assiniboines were the largest groupings. The aboriginal peoples of the West coast lived off the wealth of the sea. Settled in villages with wooden buildings, they developed hierarchical societies divided into nobles, commoners, and slaves.

In the north, above the 56th parallel, various Athapaskan speakers hunted animals such as caribou and moose in small bands and fished, while in the Arctic, the Inuit (the people) depended on sea mammals for their living.

1.2 European Background

While archaeology has shown that the Norse landed in Newfoundland at LAnse-aux-Meadowsand it is generally agreed that Leif Ericsson reached mainland North America around A.D. 1000continuous contact with Europe was not begun until fishermen began to fish off Canadas Atlantic coast in the late 1400s. French, English, Spanish, and Portuguese were soon involved.

Fishing did not require settlements. The Atlantic cod salted and preserved in barrels on board ships at sea was referred to as the wet or green fishery, while that cured on beach racks was called the shore or dry fishery. Only much later, when small settlements began, did distinctions develop between the inshore and deep sea fisheries. For over a century Canada functioned as a commercial outpost where fish were caught and furs traded with coastal Indians.

Intensive European involvement in Canada dated approximately from the creation of more centralized states in Europe, the development of better navigational tools, and competition spurred by Spanish and Portuguese interest in Mexico and South America. Most Europeans sought profits from the New World; a few searched for glory, particularly by discovering a route to the riches of Asia by sailing west; and others dreamed of making Christians of the new peoples encountered. While religious and humanitarian motives prompted a few settlements, the search for profits provided the primary motive.

1.3 Early Sojourners

King Henry VII of England commissioned Giovanni Caboto, an Italian, to search for a route to the East. In 1497, he landed at either Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island, claiming what he thought was part of Asia as an English possession. When Caboto disappeared during his second voyage in the following yearand King Henry VII diedEnglish interest in a Northwest Passage lapsed temporarily. It was resumed by Martin Frobisher, who reached Baffin Island in 1576. John Hudson, sponsored by the Dutch, sailed through the body of water that bears his name today, Hudsons Bay, and went as far south as James Bay during his last voyage in 1610.

The Portuguese were great seafarers. In 1500 and 1501, Gaspar Corte-Real reached Newfoundland. Joo Alvares Fagundes explored the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1520; and a Portuguese settlement was started on Cape Breton Island, but conflicts with aboriginal peoples led to its demise.

Fearful of Spanish expansion further to the south, King Francis I of France sent the Italian Giovanni da Verrazano, who explored the coasts (including Newfoundland) in 1524.

Jacques Cartier made three voyages in 1534, 1535, and 1541. During the second he reached Stadacona (Quebec City) and Hochelga (Montreal). Conditions were difficult, and many men died from disease and malnutrition. Cartier returned to France with iron pyrite (fools gold) and quartz crystalshence the expression for something fake, voil un diamant du Canada (thats a diamond from Canada).

Sir Humphrey Gilbert arrived at St. Johns, Newfoundland in 1583 and claimed the island for Elizabeth I, but no permanent settlement was begun. Only fishingand the trade in furs that grew from itcontinued to attract Europeans. Each year 8-10 000 European fishers crossed the Atlantic.