Mochulsky (right) and Nikolai Gradov graduated from the Moscow Institute of Railroad Transport Engineering in spring 1940.

Mochulsky (right) with fellow student and civilian worker Nikolai Gradov on board The Vologda steamship that they took up the White Sea and the Barents Sea on their way to Pechorlag, October 1940. The next several pictures depict their journey.

Mochulsky and his friend Volodia Kravtsov (in dark hats, far left) on a steamship on the Usa River in Komi, with other Gulag NKVD employees, in October 1940. The prisoners who were being transported to the same Gulag camp are held below.

An early snowstorm caused the boat Mochulsky was taking to Pechorlag to get frozen in the Usa River. On October 20, the passengers disembarked and made their way across in smaller boats, preparing to walk the rest of the way to the labor camp.

A contingent of civilian Gulag employees and prisoners crosses the Usa River on the way to Pechorlag.

When the steamship transporting workers and prisoners to Pechorlag froze in the Usa River, each Gulag employee was made responsible for getting two horses to the camp, which meant a harrowing eighteen-day walk over muddy, marshy land.

The author (right) stands at a temporary encampment in a Komi village, as the three young Gulag employees and six horses make their way to Pechorlag.

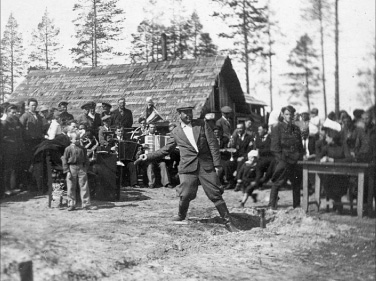

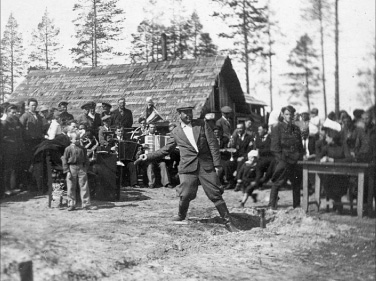

After eighteen days of walking, Mochulsky and his friends arrived at Pechorlags main Gulag administration facility in the village of Abez, in time to take part in the camps celebration of Revolution Day. A banner hails the twenty-third anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution.

On November 7, 1940, their first full day at Pechorlag, Mochulsky (right) and his friend Volodia Kravtsov attend the camps Revolution Day celebration.

Local residents of Komi province came to the Revolution Day celebration at the Gulag camp. Mochulsky (far right) stands with his friends Nikolai Gradov and Volodia Kravtsov near the reindeer.

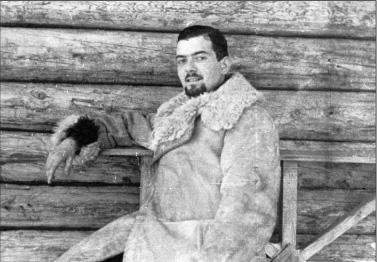

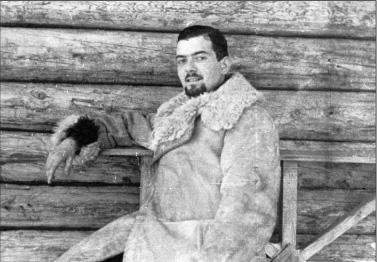

Mochulskys friend and fellow Gulag employee Volodia Kravtsov outside Pechorlags main administration building. He is wearing the sheepskin coat and padded pants that distinguished the staff from the poorly dressed prisoners at the camp.

Gulag prisoners build a rail embankment at Pechorlag in summer 1941.

Convicts clear the rail tracks after a snowstorm. On the left with a spade in his hand is First Regional Chief of Pechorlag Aleksandr Davidovich Tsfas.

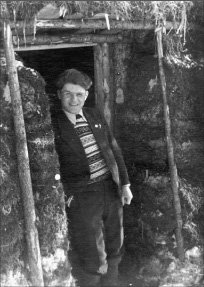

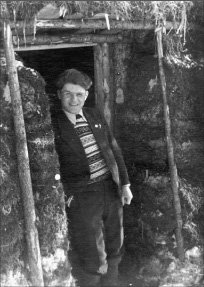

Mochulsky stands in front of the mud hut the prisoners built for him. He wears the badges he had earned earlier for mountain climbing and parachuting, which were the pride of young people in those days.

The winter of 1941-42 saw the arrival of the first trainload of coal to come from Vorkuta on the rails Mochulskys camp built.

A grenade-throwing competition for Gulag staff members at Pechora Station at Pechorlag, in the summer of 1943.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to express my profound gratitude to the many people who have helped me during the translation and annotation of Gulag Boss. I am incredibly fortunate to have Nancy Toff as my editor. She has made the otherwise long and arduous task of seeing this project through a pleasure. Likewise, Sonia Tycko at Oxford has been a tireless and gracious assistant. I am grateful to Fyodor Mochulsky for giving me the original manuscript and the photographs, the Mochulsky family in Moscow for their support and kind assistance, and to Vitaly Kozyrev for his invaluable help. A special thanks goes to Mark Kramer for his friendship, support, and generosity. Princeton University has supported this project in many ways, in particular the Sociology Department and the Program in Russian and Eurasian Studies. I want to thank Pamela Hersh for her unwavering support at all levels, David Bellos and the Program in Translation and Intercultural Communication, Antoine Kahn of Mathey College at Princeton, as well as Serguei Oukashine, Michael Wachtel, Steve Kotkin, Viviana Zelizer, Paul Starr, Alejandro Portes, Patricia Fernandez-Kelly, Doug Massey, Susan Fiske, Jan Gross, Louise Grafton, Tony Grafton, Michael Gordin, Daria Solodkaia, and of course, my wonderful Princeton students, who all thought about this project with me and added innumerable insights. Tsering Wangyal is my brilliant map-maker. A big thanks goes to Nina Gorky Shapiro, who was indispensable at guiding me to sources, finding books I needed, giving advice, and helping me with translation questions.

Jay Edson, Larry Parsons, and Miguel Centeno generously converted the little, ancient photographs into the clean copies now in the text. Ksenia Rodionova cheerfully provided much-needed Russian language clarification many times. Several people worked to make the introduction to the text as good as it is, in particular, the three anonymous reviewers for Oxford who all wrote thoughtful, helpful comments. In addition, Lynne Viola, Stephen F. Cohen, Paul R. Gregory, John Major, Dorothy Sue Cobble, and Shelley Kiernan helped me in innumerable ways on the Introduction and the Afterword. Douglas Greenberg and the USC Shoah Foundation Institute were extremely helpful, as were the professors and staff at the Iberian Studies Institute at the University of Salamanca in Spain. John W. Wright provided encouragement and assistance in the early stages. Colleagues and friends all over the place gave their kind support and suggestions, for which I am grateful: Bill Taubman, Vlad Zubok, Jay Lyle, Louis Hutchins, Alan Barenberg, Jeffrey Hass, David Brandenberger, Blair Ruble and the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies, Sally Paxton, Murray Feshbach, Amy Green, Steve Aron, Father Tim Scully, Jan Vanous, Chuck Movit, Jenny Hartshorne, and finally, the tremendous work of Arsenii Roginsky and the Memorial Society in Moscow.

Next page