Not Straight, Not White

The John Hope Franklin Series in African American History and Culture

WALDO E. MARTIN JR. AND PATRICIA SULLIVAN, editors

2016 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Utopia by codeMantra

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

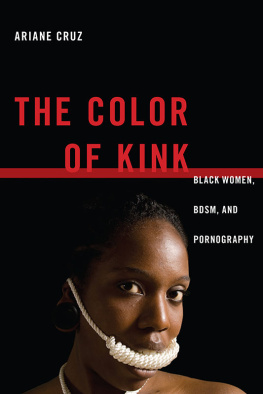

Cover illustration: iStockphoto.com/curtoicurto

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mumford, Kevin J., author.

Not straight, not white : black gay men from the march on Washington to the AIDS crisis / Kevin J. Mumford.

pages cm (The John Hope Franklin Series in African American History and Culture)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4696-2684-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4696-2685-7 (ebook)

1. African American gay men. 2. Gay men, BlackUnited States. I. Title. II. Series: John Hope Franklin series in African American history and culture.

HQ76.27.A37M86 2016

306.766208996073dc23

2015031954

In memory of a lost generation, and in hope for the next

Contents

Illustrations

1. Lorraine Hansberry

2. James Baldwin

3. Bayard Rustin

4. Jet magazine

5. Daniel Patrick Moynihan

6. Ebony magazine

7. Jason Holliday

8. Shirley Clarke

9. Dark Brothers

10. Black & Gay

11. Eldridge Cleaver

12. Fag Rag

13. Grant-Michael Fitzgerald

14. Joseph Beam

15. In the Life

16. James Tinney

17. Bayard Rustin and BWMT members

18. Joseph Beam at BWMT

Not Straight, Not White

Introduction: Corrections

In 1982, toward the end of his career, James Baldwin addressed a packed audience of the recently formed interracial gay organization Black and White Men Together (BWMT). As reported in the groups monthly newsletter, the famous black author[,] who lives in Paris, gave a lecture for BWMT-New York and its guests. This was a first for Mr. Baldwin, who had never addressed an entirely gay group before. The membership applauded Baldwins appearance as historic, reporting, The black gay religious leader, James Tinney, observed that for the first time in his career... he openly identified with the gay community by addressing more than 200 persons at a forum.

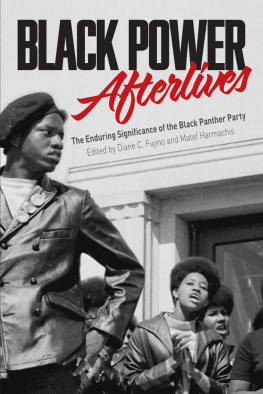

This book examines the interplay between dominant, usually stigmatizing representations of black gay men and resistance against defamation in order to understand how the pervasive repression that Baldwin and Rustin once confrontedand often lost towas transformed into a more visible, collective voice for the next generation of black gay men. It traces a winding historical path from misrecognition and marginalization to a place of shared identification while continuously subjecting to critical scrutiny the politics of representation, claims for individual sovereignty, and the promise of liberal equality.

Not Straight, Not White seeks to open conversations about black gay issues and identities with students of race and ethnic studies, civil rights and black power, and sexual and gender history, as well as to contribute to the historiography on postwar culture and social movements. LGBT historiography has largely proceeded in directions first mapped in the 1980s and early 1990s by John DEmilio, Allan Brub, George Chauncey, and Marc Stein, who practiced social and urban history to advance theoretically sophisticated investigations into the evolution of gay male organizations, neighborhoods, and identity constructions. Recent works that take up a queer methodology, such as Matt Houlbrooks Queer London, map a wide variety of male sexual encounters to challenge a certain teleology that celebrates the arrival of the once isolated homosexual in the promised land of gay liberation. Rather than a decisive historiographical break, in my view, this queer turn in the scholarship has stimulated a subtle shift in interpretive emphasis: where the first wave presented a range of same-sex encounters in homosocial settings that eventually formed a gay identification, Houlbrook discovers an urban landscape of sexual variety and argues for a disordering of identification. For some queers, class position determined their sexual options, for others renunciation of same-sex contacts and eventual entrance into straight marriage was expected, and for yet others the inversion of gender roles (usually seen as an identity mode in decline by the 1930s) proved eternally compelling as a way to make sense of and signify their sexual desires.

As more researchers engage the queer turn, wholly new sexual landscapes promise to emerge, and yet one methodological flaw that limits both the older and recent scholarship has been inattention to questions of diversity and prejudice. Many of the best and most important studies have avoided further investigation into the meanings of race for the gay past. There are a handful of exceptionsCathy Cohens Boundaries of Blackness: AIDS and the Breakdown of Black Politics, John DEmilios Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin, E. Patrick Johnsons oral history, Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South, and Joshua Gamsons The Fabulous Sylvester: The Legend, the Music, the Seventies in San Franciscobut the generalization accurately characterizes the direction of a new academic enterprise of queer studies developing along a neoliberal path toward color blindness.

The depth and reach of the new queer scholarship on sexuality in general and LGBT identity in particular has advanced our understanding of the These issues and problems turn out to be crucial to understanding the formation of individual and collective black gay identities and to remaking black gay history.

At the same time, the field of African American history has flourished over the past twenty-five years, and yet here again much of the scholarship seems to have overlooked the contributions of black gay men. The one major exception has been the reevaluation of the Harlem Renaissance as a thoroughly gay or bisexual moment, and now general textbooks in African American history recognize the queerness of the leading writers and poets of the era.

In other words, black gay lives matter. At the height of the civil rights movement, when Baldwin wrote novels that pushed the boundaries of public discourse on sexuality, he was attacked in the press and sidelined by the leadership. Bayard Rustins story has become more widely known but not entirely understood, given the role homophobia played in his marginalization not only by the respectable leadership but also by a new generation of radical activists. Even as sexual authorities, such as black physicians and social scientists, advocated for the loosening of constraints that bound black sexual expression, liberalization or further acceptance of homosexuality slowed to a halt. With the rise of black power cultural politics in the 1960s, in my reading of the archive, black men were expected to claim the same sort of sexual aggressiveness and erotic entitlement that white men had always enjoyed with relative impunity. This black power rhetoric cast adherence to the dictates of respectability and sexual restraint as the purview of the integrationist or the racial sellout, and this redefinition of black masculinity in the 1960s and 1970s reconstructed the meaning of being a black gay man in negative ways.

Questions of femininity, feminism, and lesbian identity are addressed in my narrative, but not for a sustained period or through a major focus, in part because of the need to understand better how the politics of black manhood continually restructured black gay identity. At a historic moment, James Baldwin recruited the prize-winning dramatist Lorraine Hansberry to stage a civil rights demonstration for the Freedom Riders, and studying their relationship serves to cast light on the tensions between protest for social justice and the sacrifice of sexual silence; but the preponderance of evidence about black homosexuality in media and culture before and after this singular moment overwhelmingly concerns black men, masculinity, and male homosexual etiologies. By the 1980s the emergence of black lesbian feminism clearly affected black gay identity politics, illustrated in chapter 6, which examines the influence on Joseph Beam of such towering figures in queer letters as Audre Lorde. Studies of black lesbian identity and activism are surely forthcoming, but my understanding of the extent to which constructions of masculinity structured black gay identity has determined the scope and design of my research.

Next page