The first Trades and Labour Council existed from 1881 until 1886 and was re-formed in 1889, surviving until 1912. It consisted of two delegates from each affiliated union. In 1892 it took the initiative in forming the Workers Political Committee. The executive of the T&LC and two delegates from each affiliate constituted the WPC. The WPC existed until 1905 when it retired in favour of the new national Political Labour League (190409). In the confusing period which followed, individuals and unions could join various national organisations but they took political action locally by forming a Labour Representation Committee.

In 1913, having rejected affiliation with any national organisation, the T&LC formed an Otago Labour Council with combined industrial and political functions. In 1914 the OLC affiliated with the United Federation of Labour and divested itself of its political role, forming a Labour Representation Committee. In 1916 the LRC and the OLC affiliated with the New Zealand Labour Party.

This book of essays has allowed me to draw together research done for various purposes over twenty years. I started the research for the chapters on politics in the early 1970s when asked to write an essay on unions and politics. The invitation was later withdrawn, but not before I had discovered the OtagoWorkman, Arthur McCarthys letterbooks, and the extensive archives of the Carpenters Union. I am grateful to the then secretary, Dave Cunningham, for persuading a suspicious membership that I should not only be allowed to read them but to look after them (they distrusted libraries and academics).

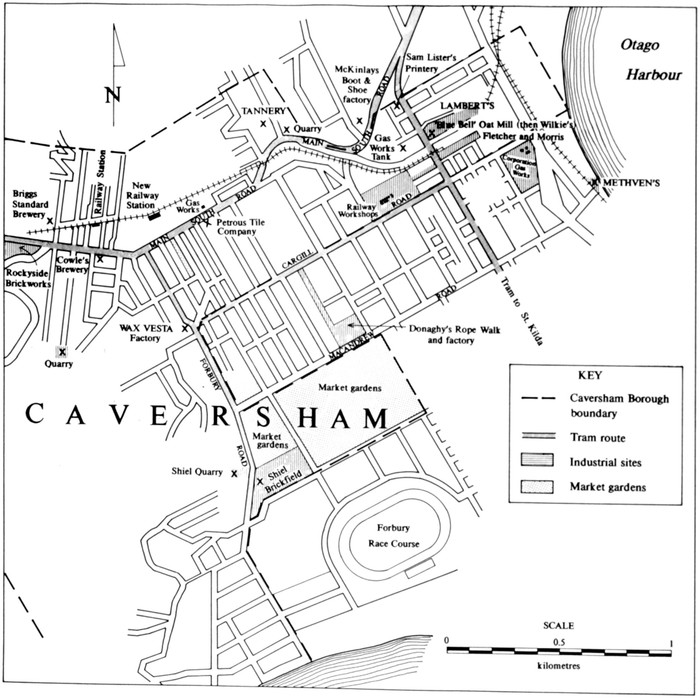

In the mid-1970s, having become familiar with Cavershams streets on behalf of various political causes, I formed the idea of focusing a major research project on the area, with a view to analysing social and geographic mobility. I invited Dr Tom Brooking to collaborate. Unfortunately the first effort to create a machine-readable data base derived from StonesDirectory and the electoral rolls, which were then not held locally, aborted because of our excessive confidence in the abilities of short-term research assistants. This only became clear in 198687 when another research assistant, hired thanks to the now defunct Social Science Research Fund Committee, tried to complete the data base. As a result all people whose last names began with letters G through T inclusive were checked and re-entered. Since then the data base has been completed. In the meantime it had become necessary to adapt the data base to the capacities of the University of Otagos (then) new mainline system. The previous system could only cope with numeric data, so all information had to be coded; the newer system had enormous advantages, despite the cost in time to the Caversham project.

In 1986 the University sought and obtained a Fulbright Fellow who reviewed the project. Dr Jeremy Brecher, a distinguished labour and social historian, recommended that because of our workloads it made sense to work together on some projects and pursue our own interests on others. At that point nobody anticipated that this collection of essays, which he urged me to work on, would appear before the collaborative work on social and geographical mobility. Dr Brooking and I taught a seminar from 1978 until 1983 on social history, based on Caversham, where I first tried to explore some of the themes in this book. That seminar proved very fruitful and I am grateful to him. Unfortunately other commitments prevented him from contributing chapters to this project (which, consequently, has become a more individual statement). I also owe a debt to Dr Brecher, not only for reviewing the project but for bringing his valuable knowledge of the labour process to Caversham. Within minutes of entering the Hillside workshops he noted not only the radical dissimilarity between Hillside and similar workshops in the United States but the centrality of the major themes in New Zealand historiography to the way in which the labour process at Hillside was organised. We have since published two papers on the labour process in the railway workshops. My own work on Hillside, in 1986, had focused on unionisation and politics, although I had begun writing the essay on the handicraft mode of production with Judi Boyd, the projects first fulltime research assistant. I am grateful to both of them for allowing me to develop those papers further.

Others have helped, including many students who participated in the Caversham seminar and my seminar on labour process in 1985. Their work is acknowledged in the footnotes. Other research assistants have also helped. Lucy Duncan, Lizzie Harrison, David Thomson, Sandy Bardsley, Stephen Clarke, Karen Duder and Tony Ballantyne have proved invaluable in various ways. Davids skill in mastering the Vax and SPSSx still astonishes me. Alan McCord and Dick Martin have also provided an indispensable source of advice whenever the computer or SPSSx have presented problems.

I would also like to thank Dr Michael Bassett for assisting me to obtain copies of all the Dunedin Central electoral rolls for the period; the old Social Science Research Fund Committee; various Research Committees of the University of Otago; and Stephen Clarke and Craig Robertson for checking footnotes. David McDonalds indefatigable energy made the final hunt for elusive references bearable. John Sullivan, photographic librarian, undertook a search for relevant photographs in Wellingtons various libraries. I also count myself lucky to have had the capable assistance of Louise Cotterall in producing six maps at rather short notice. Then there are those who read the manuscript in whole or part. Professor Ian Carter of the University of Auckland read the entire manuscript and made several useful suggestions; Professor Stuart Macintyre of the University of Melbourne read several of the chapters and drew to my attention interesting comparisons with Australia; and Dr Tom Brooking of my own University has also read the entire manuscript and made some useful suggestions. So too did Elizabeth Caffin of Auckland University Press. More importantly, she encouraged me to believe in this project at a time when I might easily have given up. Annabel Cooper, wife and critic, has helped by reading drafts and listening patiently whenever asked. She also contributed the title.

Perhaps my deepest debts are to the members of the Caversham Branch of the Labour Party during the 1970s, for it was here that I first began to make connections between the suburb in which I lived and the political processes which had transformed New Zealand. Through their families some members went back to World War I. Some of them would be amused to realise that in the course of this long journey I have finally realised the importance of work, beliefs and political action. The project has also brought me full circle. At school and university I have known and often been friends of the children and grandchildren of the men and women who constitute the actors in these essays. Doing the research has given me a reason for entering many of the buildings which I had known only from the outside. It has also given me the chance to meet and talk with many people who grew up and lived in Caversham. And last, but not least, as I grappled with the final chapter, I realised that three men who had been significant adults in my life many years ago had also shaped my path: Eric Meder, fitter and engineer; Gordon McLean, joiner and neighbour; and Mister Evans, who taught me most of what I know of carpentry. They all lived, like my family, in Andersons Bay, but, as I now realise, Caversham, at the edge of, yet part of The Flat, had colonised many of the surrounding hills. To know what that has meant you will have to keep reading.