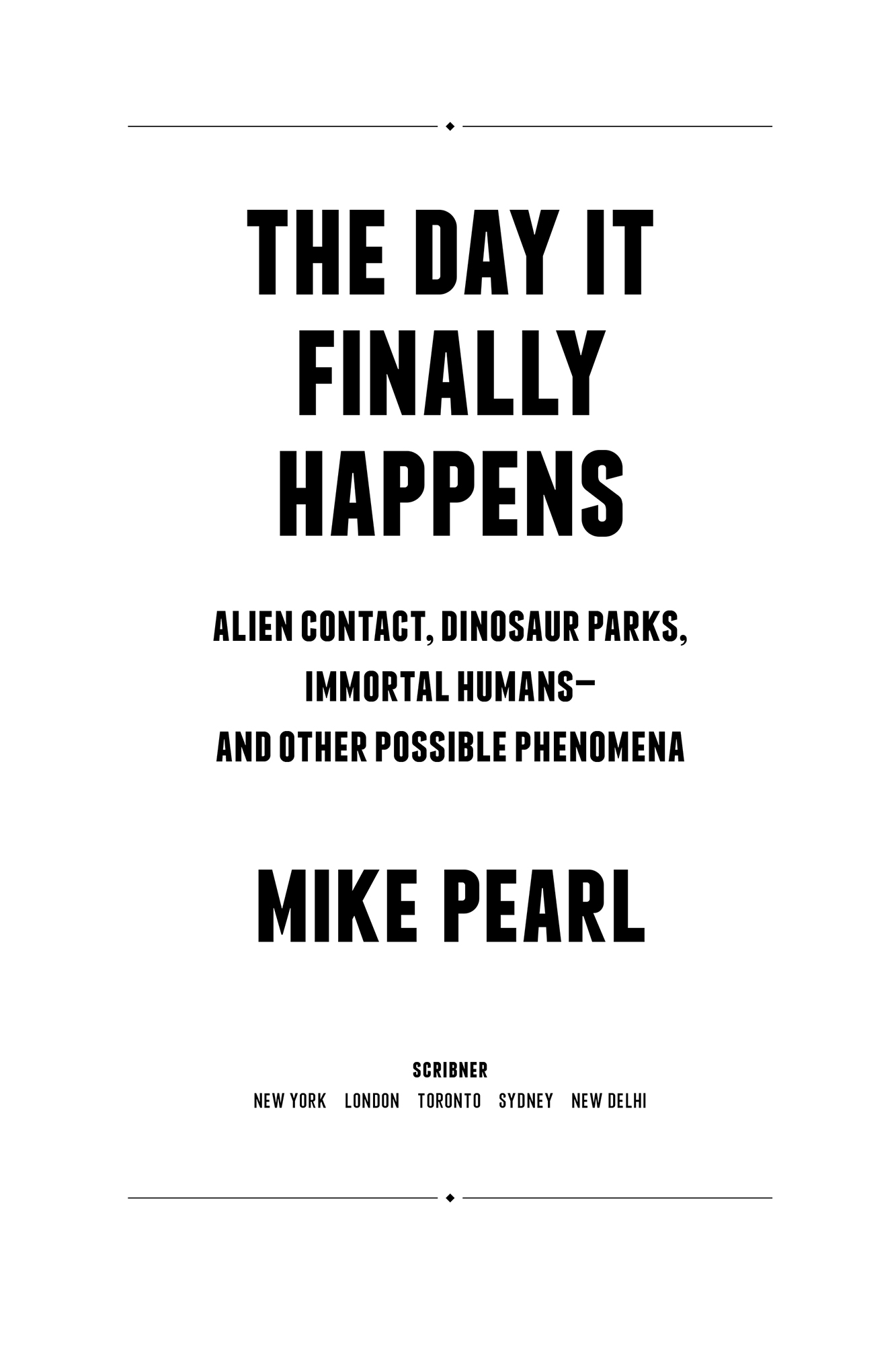

Scribner

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2019 by Mike Pearl

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Scribner hardcover edition September 2019

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Kyle Kabel

Jacket design by Tal Goretsky

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pearl, Mike, 1984 author. Title: The day it finally happens / Mike Pearl. Description: New York : Scribner, [2019] Identifiers: LCCN 2019012778 (print) | LCCN 2019014692 (ebook) | ISBN 9781501194153 (eBook) | ISBN 9781501194139 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781501194146 (pbk.) Subjects: LCSH: Forecasting. | TechnologySocial aspectsForecasting. | Social changeForecasting. | Twenty-first centuryForecasts. Classification: LCC CB161 (ebook) | LCC CB161 .P336 2019 (print) | DDC 303.49dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019012778

Photo Credits: Pages : Quasicoherent Labs, Copyright Mike Pearl 2019

ISBN 978-1-5011-9413-9

ISBN 978-1-5011-9415-3 (ebook)

For Paige, my girlfriend while I wrote this book, my fiance around the time I finished it, and my wife the week of its publication

INTRODUCTION

I f you consider yourself an informed reader who cares about the future in our supposedly post-truth world, youve probably learned the dark truth about expert forecasters. They supposedly dont know anything.

Theres data to back up this cynicism. For the book Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction , which psychologist Philip E. Tetlock wrote with journalist Dan Gardner, Tetlock gathered mountains of data about predictions, only to conclude that statistically speaking, the average expert [is] roughly as accurate as a dart-throwing chimpanzee. But still, people who predict things arent all idiots. Tetlock and Gardner discovered that some people have a knack for prediction, and they profiled them in their book. Heres what the two authors found:

Apparently, if you want to make a prediction about the future, you should base it on hard data, and that data should be completely divorced from any hunches or biases. You should deal in probabilitiesnever certaintiesand offer an unambiguous time frame.

For instance, if youre like legendary physicist Enrico Fermi, you can make seemingly psychic deductions about information you dont have by determining what data you can easily access, and then extrapolating. In his famous How many piano tuners are there in Chicago? thought experiment, Fermi asked his students to guess the number of tuners (people, not forks) to a reasonable degree of certainty with simple number crunching. We know the population of Chicago, and we know how piano tuning works. We can also calculate with some accuracy how many pianos Chicago has. So if we crunch the data, and show our work, we can come up with an estimate with a better chance of being accurate, rather than a guesstimate. Its a cool trick, but it only works when the thing youre studying is already pretty well studied.

Im not a statistician or a physicist. In fact, Im terrible at math, but I do like to predict the future, and Ive made a job of it. I just approach it a little differently because my main qualification is a paralyzing fear of things that are going to happen.

My fear comes from an anxiety disordera very common mental illness. Its a mixed blessing for someone who works as an explanatory journalist: it fills my head with ideas, but I hate the ideas. This might sound like a fun personality quirk, but if youve ever experienced a weeklong string of panic attacks, or been afraid of closing your eyes because sleep brings extreme, graphic nightmares, you know anxiety can be a whole lot more serious than just stand-up comedianesque neurosis. Im hypervigilant. Im very easy to startle (that cat-in-the-window gag is in seemingly every horror film, but it gets me every time). Im fidgety. I constantly scan my surroundings for exits.

As part of what I guess you could call a coping strategy, I started writing my Vice column How Scared Should I Be? in which I tried to assess the rationality of my own fears. Writing about what scared methings like terrorism, pit bulls, choking, and getting punched in the facewas a revelation. That experience led to my series of climate change predictions called Year 2050, and my hypothetical war series, Hours and Minutes. These articles werent just therapy; through them, I learned that millions of people share my fears. And for a time, I felt a twinge of guilt: Is it okay to exploit peoples fear for clicks? I wondered. But then my girlfriend (my most loyal reader) pointed out that understanding the details of a terrifying topic is weirdly empowering, even comforting.

Of course, occasionally, after a thorough excavation of the facts, Ive been forced to break the newsto myself and the readers of Vice that were not scared enough. For example: I assigned my highest fear rating ever to never retiring because, after researching the topic, I decided that my peers should be much more afraid of it than they already are. So yes: by definition, Im fearmongering.

But I see that as a net positive, too. After all, we evolved to experience fear because it saves us from harm. Evolution may not have taught us inhabitants of the modern world to allocate our fears judiciously, but with a little research, we can make some necessary adjustments. I find it reassuring to know that some of the stuff thats ostensibly scary is also actually scary. It makes me feel sane.

But let me be clear: this isnt a self-help book, and Im not going to make any claims about how I can rescue you, too, from anxiety if you follow my step-by-step plan . I still believe, however, that envisioning future possibilities in a sensible, fact-based way is a helpful habit that leads to clearer thinking. Since writing about speculative scenarios became my job, Ive trained myself, whenever my knee-jerk response to something is fear, to stop and look at likely outcomes and real-world implications rather than imagine the apocalypse. Or, if I have to concede the possibility of the apocalypse, I ask myself, would it really be so bad?

* * *

The most therapeutic article Ive ever written wasnt about the future at all. It was called How Scared Should I Be of Pit Bulls? Ive dealt with a fear of dogs for most of my adult life, ever since 2006, when a dog I swear was the size of a lion lunged at me on a sidewalk in Budapest. It wasnt a life-threatening incident (the owner pulled the dog off me a second later, and the bite didnt even require a Band-Aid), but the shock has stayed with me. One moment that dog was someones well-groomed peta good boy or girl, if you willand the next it wanted me dead.

Even so, I brought an open mind to my investigation, and it turned out that, yes, dogs described as pit bulls are involved in far more fatal attacks than any other type of dog, but science cant really nail down what a pit bull is, which complicates the whole matter of the breeds inherent scariness. But I also learned that dogspit bull or otherwisesimply arent dangerous enough to be a threat to most humans, There are only about twenty-six dog-related fatalities a year in the US, which is less than the number of fatalities from falling tree limbs. And the vast majority of human victims have either been babies or the very elderly. Whats more, thats 26 out of the approximately 4.5 million annual dog bitesincluding nips on the hand.