About the Author

Dr. Hank Prunckun, BS, MSocSc, PhD, is associate professor of intelligence analysis at the Australian Graduate School of Policing and Security, Charles Sturt University, Sydney. He specializes in the study of transnational crimeespionage, terrorism, drugs and arms trafficking, and cyber crime. He is the author of numerous reviews, articles, chapters, and books, including Intelligence and Private Investigation: Developing Sophisticated Methods for Conducting Inquiries (Charles C Thomas, 2013); Counter-intelligence Theory and Practice (Rowman & Littlefield, 2012); Handbook of Scientific Methods of Inquiry for Intelligence Analysis, first edition (Scarecrow Press, 2010); Shadow of Death: An Analytic Bibliography on Political Violence, Terrorism, and Low-Intensity Conflict (Scarecrow Press, 1995); Special Access Required: A Practitioners Guide to Law Enforcement Intelligence Literature (Scarecrow Press, 1990); and Information Security: A Practical Handbook on Business Counterintelligence (Charles C Thomas, 1989). He is the winner of two literature awards and a professional service award from the International Association of Law Enforcement Intelligence Analysts, and is editor-in-chief of Salus Journal, associate editor of the Australian Institute of Professional Intelligence Officers Journal, and the International Association of Law Enforcement Intelligence Analysts Journal. Dr. Prunckun has served in a number of strategic research and tactical intelligence capacities within the criminal justice system during his twenty-eight-year operational career, including almost five years as a senior counterterrorism policy analyst during the Global War on Terror. In addition, he has held a number of operational postings in investigation and security. Dr. Prunckun is also a licensed private investigator.

Appendix

Critical Values of Chi-Square Distribution

| Degrees of Freedom | P .05 | P .01 |

| 1 | 3.84 | 6.64 |

| 2 | 5.99 | 9.21 |

| 3 | 7.82 | 11.35 |

| 4 | 9.49 | 13.28 |

| 5 | 11.07 | 15.09 |

| 6 | 12.59 | 16.81 |

| 7 | 14.07 | 18.48 |

| 8 | 15.51 | 20.09 |

| 9 | 16.92 | 21.67 |

| 10 | 18.31 | 23.21 |

| 11 | 19.68 | 24.73 |

| 12 | 21.03 | 26.22 |

| 13 | 22.36 | 27.69 |

| 14 | 23.69 | 29.14 |

| 15 | 25.00 | 30.58 |

| 16 | 26.30 | 32.00 |

| 17 | 27.59 | 33.41 |

| 18 | 28.87 | 34.81 |

| 19 | 30.14 | 36.19 |

| 20 | 31.41 | 37.57 |

| 21 | 32.67 | 38.93 |

| 22 | 33.924 | 0.29 |

| 23 | 35.17 | 41.64 |

| 24 | 36.42 | 42.98 |

| 25 | 37.65 | 44.31 |

Note: This is a facsimile of a table of critical values of chi-square. It has been reproduced here using data that is in the public domain.

Intelligence Theory

T his topic provides an introduction to intelligence research by examining:

- Intelligence research;

- Why intelligence;

- Information versus intelligence;

- Intelligence defined;

- Intelligence as knowledge;

- Intelligence as a process;

- Intelligence versus investigation;

- Data versus information; and

- Intelligence theory.

INTELLIGENCE RESEARCHA HARD ROW TO HOE

It could only be described as a typical winters day in late January 1993. Like most days, a line of traffic came to a halt at a set of traffic lights on the eastbound lane of Virginia Route 123. This place was just outside the entrance to CIA headquarters in Fairfax County, Virginia. In the line of cars waiting to go to work were CIA staffers and various contractors. It was a routine day for them as well as the many intelligence analysts who were already at work within the complex.

On such a day, one would not expect analysts to face anything more dangerous than the hazard posed by some careless driver. But intelligence workno matter how remote analysts are from the James Bondlike scenarios of intelligence gatheringis a profession fraught with danger.

On January 23, 1993, a Pakistani assassin in that same line of traffic got out of his car at the stoplight and walked calmly from vehicle to vehicle shooting the male occupants with his AK-47 assault rifle. He only stopped firing because, as he later confessed, he ran out of targets. Among those wounded and dead were intelligence analysts.

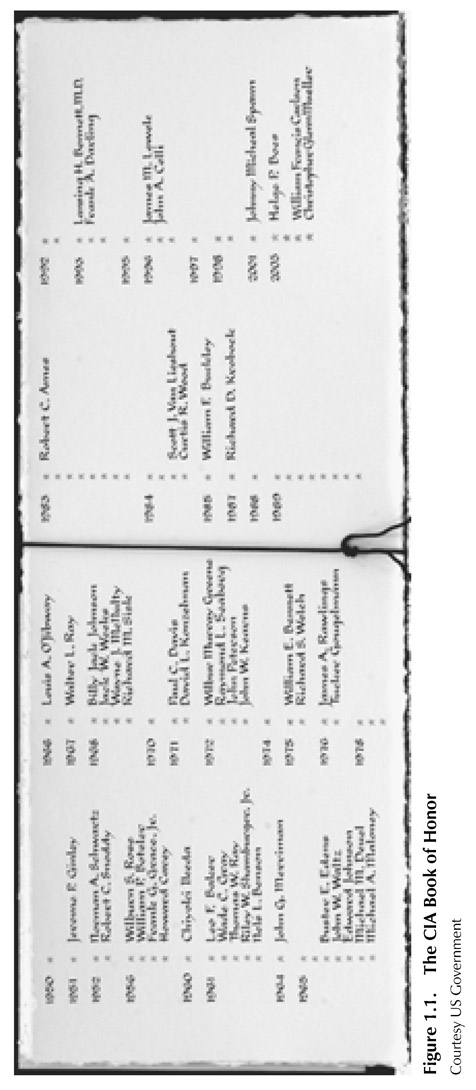

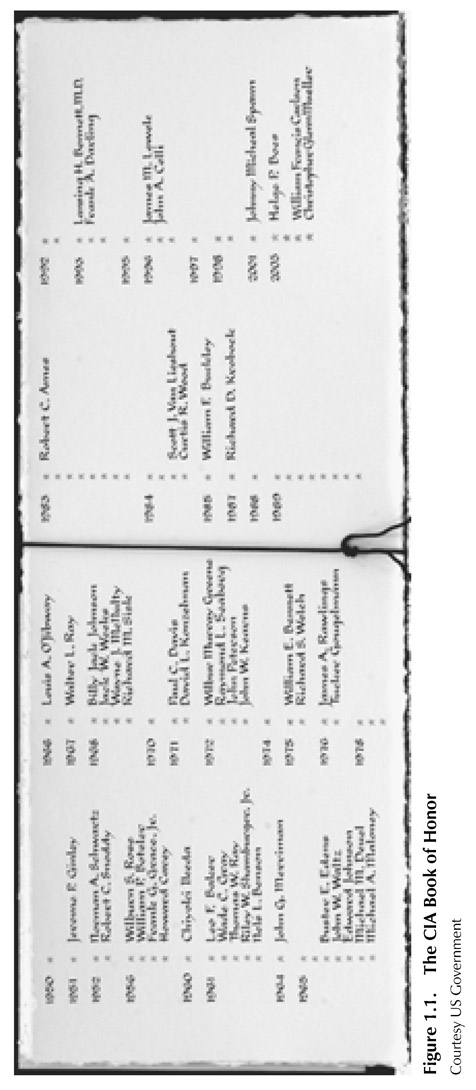

Although this book is a critical discussion of intelligence researcha seemingly urbane professionmake no mistake: intelligence work carries with it dangers. The CIA Memorial Wall (and Book of Honor, see figure 1.1) displays stars that represent those who gave their lives for their country in the service of intelligence.

WHY INTELLIGENCE

Why be concerned with intelligence? Because intelligence enables one to exercise control over a given situation. In this sense, control equates to power. Ira Cohen, in his classic treatment of the study of power, wrote:

Power is sought because without power the security and even the ability of [one] to continue to exist is generally decreased. Without power, [one] has no ability to deter another... from actions whose consequences threaten the vital interests of the former. Without power [one] cannot cause another... to do that which the former desires but which the latter desires not to do. Power is sought because the more power that [one] has, the greater is the number of [his or her] available options. The more options available to [one], the greater [his or her] security. The greater [his or her] security, the better off [he or she is]. [He or she is] more secure in [his or her] life and in the enjoyment of [his or her] private property.

Intelligence is, therefore, not a form of clairvoyance used to predict the future but an exact science based on sound quantitative and qualitative research methods. But as Lowenthal points out: Intelligence is not about truth. If something were known to be true, states would not need intelligence agencies to collect the information or analyze it.... [So,] we should think of intelligence as a proximate reality.... [Intelligence agencies] can rarely be assured that even their best and most considered analysis is true. Their goals are intelligence products that are reliable, unbiased, and honest (that is, free from politicization). In this regard, intelligence enables the analyst to present solutions or options to decision makers based on defensible conclusions.

But at this juncture it should be noted that such conclusions are not absolute, and there will always be some level of probability or uncertainty involved with presenting intelligence findings (i.e., proximate reality). Nevertheless, uncertainty can be reduced and conclusion limits further defined so decision makers understand the boundaries. This must be contrasted with making decisions based on a hunch, instinct, luck, gut feel, belief, faith, trust, or hope.

Critical Values of Chi-Square Distribution

Critical Values of Chi-Square Distribution