TO

FIGHT

AGAINST

THIS

AGE

ROB RIEMEN

For Eveline

Our age reminds one very much of the disintegration of the Greek state; everything continues and yet, there is no one who believes in it. An invisible bond that gives it validity, had vanished, and the whole age is simultaneously comic and tragic, tragic because it is perishing, comic because it continues.

SREN KIERKEGAARD, EITHER/OR

CONTENTS

TO

FIGHT

AGAINST

THIS

AGE

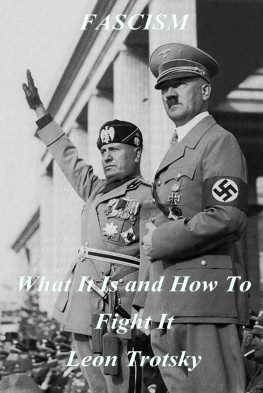

In 2010 I published in my country, the Netherlands, an essay entitled The Eternal Return of Fascism, at a time when it was already obvious to me that a fascist movement was on the rise again. If this could happen in an affluent welfare state like the Netherlands, I realized, the return of fascism in the twenty-first century could happen anywhere. The small book became an instant best seller despite the ferocious and angry criticism of the political and academic class. Their state of denial surprised me and still worries mebecause I do agree with Arnold Toynbee when he, in his magnum opus A Study of History, argued that civilizations would fall, not because it was inevitable but because governing elites wouldnt respond adequately to changing circumstances or because they would focus only on their own interests.

Wise men like Confucius and Socrates knew that to be able to understand something, you had to call it by its proper name. The term populism , being the preferred description for a modern-day revolt of the masses, will not provide any meaningful understanding concerning that phenomenon. The late Judith Shklar, a renowned political theorist at Harvard University, was absolutely right when she wrote, at the end of Men and Citizens , her study on Rousseaus social theory, that populism

is a very slipper term, even when applied to ideologies and political movements. Does it refer to anything more specific than a confused mixture of hostile attitudes? Is it simply an imprecise way of referring to all those who are neither clearly left nor right? Does the word not just cover all those who have been neglected by a historiography that can allow no ideological possibilities other than conservative, liberal and socialist, and which oscillates between the pillars of right and left as if these were laws of nature? Is populism anything but a rebellion that has no visa to the capitals of conventional thought?

The use of the term populist is only one more way to cultivate the denial that the ghost of fascism is haunting our societies again and to deny the fact that liberal democracies have turned into their opposite: mass democracies deprived of the spirit of democracy. Why this denial?

One reason may be that from the perspective of science and technology, ghosts and spirits do not exist. Which of course is truefor Mother Nature. Human nature and human society are, however, a different species. Science and technology will never be able to provide us with a complete understanding of the human being with his instincts and desires, virtues and values, mind and spirit. Every serious scientist knows this. Alas, not that many in our ruling class do. Their understanding of society is limited by the scientific paradigm of proofs, data, theories, and definitions. The humanities and the arts are therefore ignored and dismissed. Yet the only knowledge that could provide a true understanding of the human heart, the perennial complexities of societies with their conflicting interests, the causes of modern-day movements and upheavals, and the real requirements of a democratic civilization is the wisdom of poetry and literature, philosophy and theology, the arts and history. This is the domain of culture; this is where we can find Clio, the Muse of history, always with a book in her hands, offering us the gift of historical awareness. But one has to read books to get to know her and benefit from her gifts.

A second reason the return of fascism and the loss of the democratic spirit are hard to accept is the embarrassment of the political left that embraces the tradition of the Enlightenment. The mindset around its articles of faithhuman progress, the natural goodness of man, rationality, institutions, and political and social values as the main pillars of a just societywill always make it difficult to recognize the impact that the will to power, lust, desire, and self-interest have on the human condition. The point is, we human beings are as irrational as we can be rational, and fascism is the political cultivation of our worst irrational sentiments: resentment, hatred, xenophobia, lust for power, and fear!

Facing a fascist Europe, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt knew what he was talking about in March 1933 when he declared in his first inaugural address, The only thing we have to fear... is fear itself! He was well aware that societies in the grip of fear are responsive to the false promises of the fascist ideology and of autocratic leaders.

A sense of crisis, economic insecurity, and the threat of terror or war are the acknowledged causes of a climate of fear. The incompetence to prevent the return of fascism, to fight and eliminate it, is also due to an unacknowledged cause of fear and the main reason fascism can return so easily in mass democracies: ignorance . This is the third reason the denial of fascism prevails in our times. Acceptance of this fact includes the awareness that despite all our scientific and technological progress, the worldwide access to information and a provision of higher education for everybody who can afford it, the dominant force in our society is organized stupidity...

In my 2008 book Nobility of Spirit: A Forgotten Ideal, the final chapter Be Brave is devoted to the life of an exceptional man, a fighter against his time, Leone Ginzburg. A Russian Jew born in 1909, Ginzburg as a child emigrated with his family to Italy. He was a brilliant man who translated the wonderful brick of a novel, Tolstoys Anna Karenina, into Italian when he was just eighteen. Transmitting and making accessible the best of the European spiritgreat literaturewould become his strong passion. He translated, taught, founded a publishing house, and set up a magazine, Cultura (Culture), to do justice to the original meaning of the word: making room for the collection of the many roads people can travel in their search for the truth about themselves and human existence. Realizing that only culture can help people figure out the truth about their own lives and actions, he made transmitting European culture his lifes work.

But then Mussolini and his fascists came into power in Italy. Mussolini insisted that all professors sign a declaration of loyaltyor lose their jobs. Of the eleven hundred professors, only ten (!) refused to sign. Leone Ginzburg was one of those ten. (Courage is a rare trait in the academic and intellectual world too.) He joined the resistance because he knew that culture and freedom cannot exist without each other. He also knew that fascismwhich always crops up in the name of freedomwants only to destroy freedom.

Ginzburg was arrested and deported. When Mussolini was overthrown, Ginzburg returned to Rome to fight against the Nazis who had taken over. He was arrested again and then tortured to death by the Nazis at the age of thirty-five. A letter he wrote from prison to his wife Nataliait would turn out to be his lastends as follows:

Dont worry too much about me. Just imagine that I am a prisoner of war; there are so many, particularly in this war, and the great majority will return home. Let us hope that Im part of that majority, eh Natalia? I kiss you again and again and again. Be brave.

Next page