First published 2017

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2017 Brigitte Sbastia, selection and editorial material; individual chapters, the contributors

The right of the editor to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Names: Sbastia, Brigitte, editor.

Title: Eating traditional food : politics, identity and practices / edited

by Brigitte Sbastia.

Description: London ; New York : Routledge is an imprint of the

Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa Business, [2017] | Includes

bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016021306| ISBN 9781138187009 (hbk) |

ISBN 9781315643410 (ebk)

Subjects: LCSH: Food habits--Cross-cultural studies. | Food

consumption--Cross-cultural studies. | Nutrition--Cross-cultural

studies. | Food--Cross-cultural studies. | Social psychology

-Cross-cultural studies.

Classification: LCC GT2850 .E37 2017 | DDC 394.1/2--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016021306

ISBN: 978-1-138-18700-9 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-64341-0 (ebk)

Typeset in Bembo

by HWA Text and Data Management, London

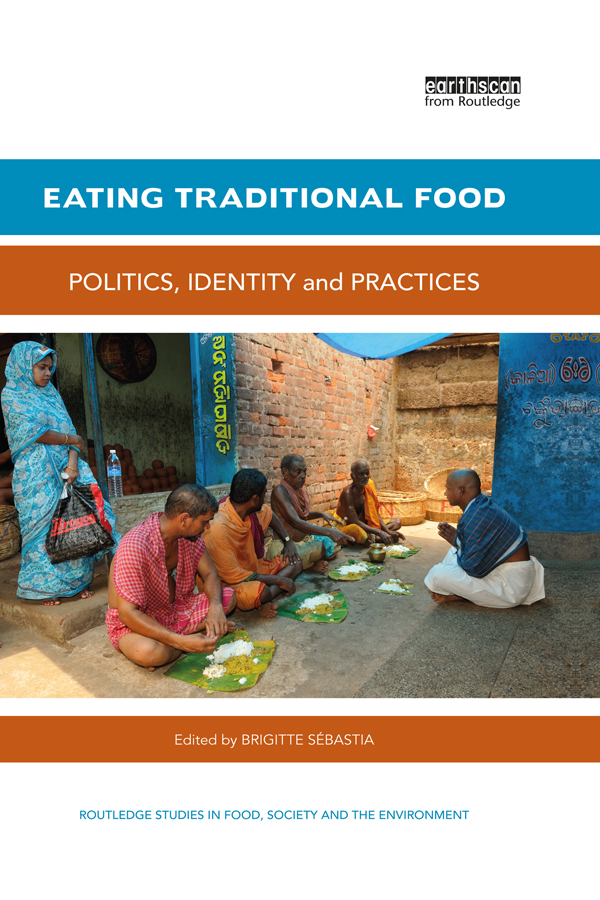

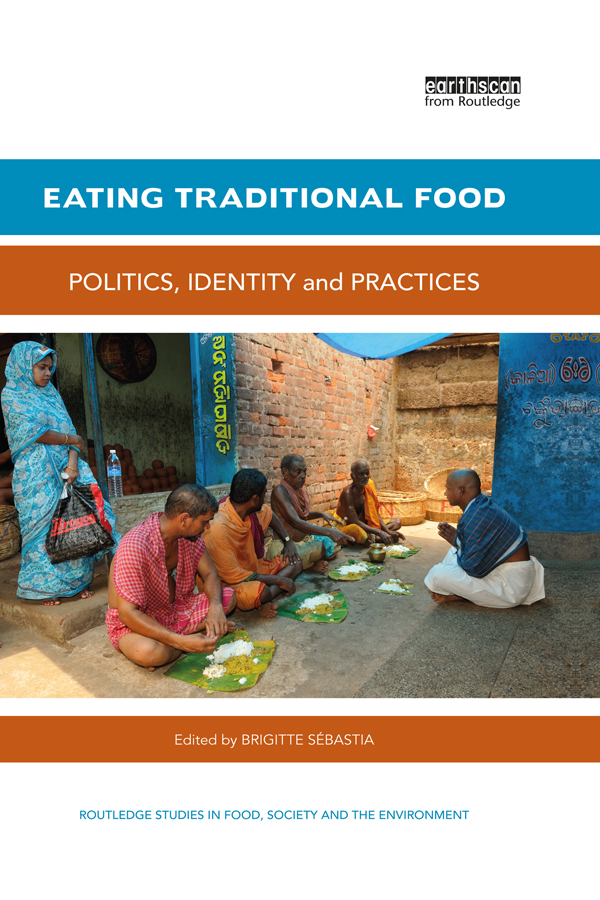

Eating Traditional Food: politics, identities and practices wrestles down the concept and practices of producing and consuming traditional foods, without falling either into the ethnocentric, nationalist rendering of tradition, or the blanket denunciation of the very concept of tradition by critical scholars, who thereby abandon any notion of common practices over time, which can be used to contain invented traditions and criticise market and state manipulation of heritage. We are reminded that tradition is the production of the past in the present. The authors do a great service in trying to draw the boundaries of the modern and traditional, the past and present, community and consumer practices. They, thus, enable us to protect what comes from a long duration and is widely shared by the commons without the protection of intellectual property rights, against the encroachment of private, commodified, consumer culture, undertaken primarily for profit and for social prestige. Nevertheless, the authors complicate the effort by drawing lines of filiation between the apparent polar opposites such as the modern and the traditional. We are made aware that tradition, like authenticity, is both practically and politically necessary, while conceptually fraught, in terms of whose tradition is being valorised and whose customs slighted. There is no easy way to identify tradition without engaging with insidious epistemologies of power, and the power to erase practices, or make some practices more visible than others at a particular conjuncture.

For instance, in the exemplary case of meat eating in India, which of the many traditions among Vedic texts, Brahmin teachings, Muslim custom and Dalit practices can and must be valorised, practices that were often deployed against each other? How long does a practice have to be practised to become traditional? The chapter on Malta underlines the exquisite paradox where olive oil and wine production, that were abandoned a millennium ago, are re-introduced as traditional practices, while the seven-decade-old production of a soft, fizzy, drink that is widely consumed, such as Kinnie, is ignored in the consecration of the traditional among a newer cosmopolitan class, in alliance with organisations such as the European Commission and UNESCO, with an acute awareness of their new-found and newly valued Mediterraneanness. There is some sense that a practice has to be good by some definition to be protected. Who gets to decide what is good and what is the process of doing that?

Other questions remain: do 500 years of the continuous presence of Islam make halal an Indian tradition? Can a mere century of tea drinking, in spite of its ubiquity, be adequate to mark it as a quintessentially Indian tradition? Does a millennium of intoxication of various fermented and distilled drinks, count towards an Indian tradition, even if there is minimal textual evidence for it? When do invaders become settlers, and settlers, natives? Much hinges on drawing a temporal line of belongingness across social fields. Many of these questions are interrogated in this book, along with epistemological issues of visibility and invisibility, textual residue, the power of paperwork, and the evanescence of oral practices, both in the realm of taste and of talk.

One thing we learn repeatedly is that contingency is crucial: the threat of transgenic maize was the trigger for the mobilisation of the idea and state policy of Mexican gastronomic tradition as submitted and accepted by UNESCO; the recent wave of Hindu nationalist mobilisation and polarisation has been vital to revivifying the question of beef-eatings Indianness; and the crisis of confidence in modern science and the distribution of risk is key to the emplacement of Ayurveda in France; while the reinvigorated disenfranchisement of Palestinians is fundamental to the contestation around traditional Palestinian foods, such as hummus. So, the authors struggle to find a tradition, if they are to speak at all of dispossession and appropriation by others, no matter how fraught that definition. Which leads immediately to further questions of methods of preservation of legitimate traditional practices is it best to do so by everyday practice, market power or state policy?

Dietary prescription, apparently ubiquitous today, is in fact an old social habit. Nutritional advice is a venerable tradition of the dissemination and imposition of expert knowledge, to inform and contain lay practices. The history of the production and consumption of amaranth, chapulines , and pulque , in Mexicos Central Highlands, for instance, are entangled with questions of class and race, tourism, national politics and indigeneity. As illustrated in the compelling chapter by Katz and Lazos, pulque , the fermented beverage from the agave plant, which typically grows above altitudes of 1500 metres, was an important traditional indigenous drink and food (children often consumed it for breakfast); it was appropriated by Spanish elites (as an intoxicant along with wine) in the seventeenth century, but came to be thought of as a primitive drink of the savage Indians by the end of the nineteenth century. In particular, the antipathy towards pulque deepened when the hacendados from the South were the target of the revolutionaries of 1910. By 1923, the new regime enacted alcohol taxes that disadvantaged pulque over the newly emergent urban and cosmopolitan beer. The alliance between the post-revolutionary government, religious authorities and German immigrants reconfigured beer as a more modern, healthy and hygienic drink, because it was bottled and refrigerated, and it became the most popular alcoholic beverage, even in indigenous villages.