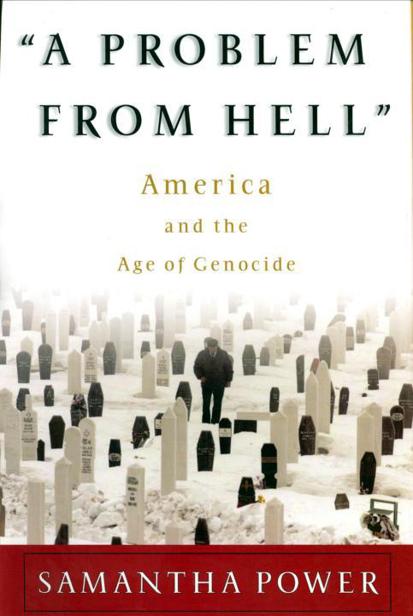

Samantha Power - A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide

Here you can read online Samantha Power - A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2007, publisher: Harper Perennial, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide

- Author:

- Publisher:Harper Perennial

- Genre:

- Year:2007

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

"A PROBLEM FROM HELL"

"A PROBLEM

FROM HELL"

America and the Age of Genocide

Samantha Power

For Mum and Eddie

"We-even we here-hold the power, and bear

the responsibility."

-ABRAHAM L I N C O L N

Contents

xi

1 1

Preface

My introduction to Sidbela Zimic, a nine-year-old Sarajevan, came unexpectedly one Sunday in June 1995. Several hours after hearing the familiar whistle and crash of a nearby shell, I traveled a few blocks to one of the neighborhood's once-formidable apartment houses. Its battered facade bore the signature pockmarks left from three years of shrapnel spray and gunfire. The building lacked windows, electricity, gas, and water. It was uninhabitable to all but Sarajevo's proud residents, who had no place else to go.

Sidbela's teenage sister was standing not far from the entrance to the apartment, dazed. A shallow pool of crimson lay beside her on the playground, where one blue slipper, two red slippers, and a jump rope with icecream-cone handles had been cast down. Bosnian police had covered the reddened spot of pavement with plastic wrapping that bore the cheery baby blue and white emblem of the United Nations.

Sidbela had been known in the neighborhood for her bookishness and her many "Miss" pageants. She and her playmates made the best of a childhood that constrained movement, crowning "Miss Apartment Building," "Miss Street Corner," and "Miss Neighborhood." On that still morning, Sidbela had begged her mother for five minutes of fresh air.

Mrs. Zimic was torn. A year and a half before, in February 1994, just two blocks from the family's home, a shell had landed in the main downtown market, tearing sixty-eight shoppers and vendors to bits. The graphic images from this massacre generated widespread American sympathy and galvanized President Bill Clinton and his NATO allies. They issued an unprecedented ultimatum, in which they threatened massive air strikes against the Bosnian Serbs if they resumed their bombardment of Sarajevo or continued what Clinton described as the "murder of innocents."

"No one should doubt NATO's resolve," Clinton warned. "Anyone," he said, repeating the word for effect, "anyonne shelling Sarajevo must ... be prepared to deal with the consequences."' In response to America's perceived commitment, Sarajevo's 280,000 residents gradually adjusted to life under NATO's imperfect but protective umbrella. After a few cautious months, they began trickling outside, strolling along the Miljacka River and rebuilding cafes with outdoor terraces.Young boys and girls bounded out of dank cellars and out of their parents' lines of vision to rediscover outdoor sports. Tasting childhood, they became greedy for sunlight and play. Their parents thanked the United States and heaped praise upon Americans who visited the Bosnian capital.

But American resolve soon wilted. Saving Bosnian lives was not deemed worth risking U.S. soldiers or challenging America's European allies who wanted to remain neutral. Clinton and his team shifted from the language of genocide to that of "tragedy" and "civil war," downplaying public expectations that there was anything the United States could do. Secretary of State Warren Christopher had never been enthusiastic about U.S. involvement in the Balkans. He had long appealed to context to ease the moral discomfort that arose from America's nonintervention. "It's really a tragic problem," Christopher said. "The hatred between all three groups-the Bosnians and the Serbs and the Croatians-is almost unbelievable. It's almost terrifying, and it's centuries old. That really is a problem from hell .112 Within months of the market massacre, Clinton had adopted this mindset, treating Bosnia as his problem from hell-a problem he hoped would burn itself out, disappear from the front pages, and leave his presidency alone.

Serb nationalists took their cue.They understood that they were free to resume shelling Sarajevo and other Bosnian towns crammed with civilians. Parents were left battling their children and groping for inducements that might keep them indoors. Sidbela's father remembered, "I converted the washroom into a playroom. I bought the children Barbie dolls, Barbie cars, everything, just to keep them inside." But his precocious daughter had her way, pressing, "Daddy, please let me live my life. I can't stay at home all the time."

America's promises, which Serb gunners took seriously at first, bought Sarajevans a brief reprieve. But they also raised expectations among Bosnians that they were safe to live again. As it turned out, the brutality of Serb political, military, and paramilitary leaders would be met with condemnation but not with the promised military intervention.

On June 25, 1995, minutes after Sidbela kissed her mother on the cheek and flashed a triumphant smile, a Serb shell crashed into the playground where she, eleven-year-old Amina Pajevic, twelve-year-old Liljana Janjic, and five-year-old Maja Skoric were jumping rope. All were killed, raising the total number of children slaughtered in Bosnian territory during the war from 16,767 to 16,771.

If any event could have prepared a person to imagine evil, it should have been this one. I had been reporting from Bosnia for nearly two years at the time of the playground massacre. I had long since given up hope that the NATO jets that roared overhead every day would bomb the Serbs into ceasing their artillery assault on the besieged capital. And I had come to expect only the worst for Muslim civilians scattered throughout the country.

Yet when Bosnian Serb forces began attacking the so-called "safe area" of Srebrenica on July 6, 1995, ten days after I visited the grieving Zimic family, I was not especially alarmed. I thought that even the Bosnian Serbs would not dare to seize a patch of land under UN guard. On the evening of July I(), I casually dropped by the Associated Press house, which had become my adopted home for the summer because of its spirited reporters and its functional generator. When I arrived that night, I received a jolt. There was complete chaos around the phones. The Serb attack on Srebrenica that had been "deteriorating" for several days had suddenly "gone to hell." The Serbs were poised to take the town, and they had issued an ultimatum, demanding that the UN peacekeepers there surrender their weapons and equipment or face a barrage of shelling. Some 40,000 Muslim men, women, and children were in grave danger.

Although I had been slow to grasp the magnitude of the offensive, it was not too late to meet my American deadlines. A morning story in the Washington Post might shame U.S. policymakers into responding. So frantic were the other correspondents that it took me fifteen minutes to secure a free phone line. When I did, I reached Ed Cody, the Post's deputy foreign editor. I knew American readers had tired of bad news from the Balkans, but the stakes of this particular attack seemed colossal. Bosnian Serb general Ratko Mladic was not dabbling or using a petty landgrab to send a polit ical signal; he was taking a huge chunk of internationally "protected" territory and challenging the world to stop him. I began spewing the facts to Cody as I understood them: "The Serbs are closing in on the Srebrenica safe area. The UN says tens of thousands of Muslim refugees have already poured into their base north of the town center. It's only a matter of hours before the Serbs take the whole pocket.This is a catastrophe in the making. A United Nations safe area is going to tall"

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide»

Look at similar books to A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.