Discover why this book was selected by the Book-of-the-Month Club, the Jewish Book Club, and the History Book Club.

Powerful Remarkable freshness and originality Leaves no aspect of the complex Arab-Jewish relationship untouched. Presented in an abundance of narratives, anecdotes and conversations that never seem hackneyed.

The New York Times Book Review

Finally a Western journalist has left the experts and the elites for the people themselves. Shipler has penetrated far into foreign feelings and foreign cultures. And he writes with great moral poise.

The New Republic

With an eye for detail and subtleties, Shipler provides anecdotes that are rich in meaning.

Israel Today

The picture Shipler paints is chilling. Poignant.

Chicago Tribune

Critical yet compassionate, Arab and Jew offers a comprehensive guide for anyone wishing to learn about these neighbors and enemies living uneasily side by side.

USA Today

ARAB

and

JEW

Wounded Spirits in

a Promised Land

Revised and Updated

DAVID K. SHIPLER

B\D\W\Y

Broadway Books

New York

Copyright 1986, 2002 by David K. Shipler Living Trust

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Broadway Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

Broadway Books and its logo, B \ D \ W \ Y, are trademarks of Random House LLC.

Originally published in hardcover by Times Books, a division of Random House LLC in 1986 and in an updated paperback edition by Penguin Books in 2002.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shipler, David K., 1942

Arab and Jew : wounded spirits in a promised land / David K. Shipler.Rev. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0 14 20.0229 1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Jewish-Arab relations. 2. Arab-Israeli conflict. 3. IsraelEthnic relations. 4. West Bank

Ethnic relations. 5. Gaza StripEthnic relations. 6. National characteristics, Arab. 7. National

characteristics, Israeli. I. Title.

DS119.7 .S476 2002

956.9405dc21 2001054862

eISBN: 978-1-101-90304-9

Cover design by Michael Morris

v3.1

For

Jonathan, Laura, and Michael

Go, set a watchman, let him declare what he seeth.

Isaiah 21:6

The spirit of a man will sustain his infirmity; but a wounded spirit who can bear?

Proverbs 18:14

FOREWORD

TO THE

REVISED

EDITION

T his book was originally written in a more innocent time. That may seem an odd characterization of the Israeli-Arab conflict, which has never been conducted according to Queensberry rules. Nasty, grinding, and brutalizing, the struggle still respected certain boundaries. Palestinians had not begun to use suicide bombers against Israeli civilians. Israel had not made routine use of tanks, artillery, and helicopters against Palestinian residents of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Nor had Israel yet offered to end its occupation of those territories, so the hope prevailed that such withdrawal would end the strife.

Terrorist acts in most of the world were spectacular but relatively small in scale. They did not rise to the level of mass murder until the extermination of several thousand people on the morning of September 11, 2001, when Muslim hijackers crashed airliners into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Americans had not previously realized how deeply entangled they were in the religious and nationalist clashes of the Middle East.

Despite appeals from President George W. Bush for tolerance toward Muslims, some Americans behaved the way some Israelis do following a terrorist attack. Mosques in the United States were defaced, Arab-owned stores were vandalized, men with Arab-sounding names were thrown off planes by pilots and passangers, swarthy Americans were threatened, and several were murdered. Racial profiling suddenly became acceptable when aimed at those with a Middle-Eastern look, just as Israeli security routinely focuses on Arabs as the main source of danger. And many other Americans offered an outpouring of support to their Muslim neighbors, opposed the governments curtailment of civil liberties, and questioned themselves as painfully as many Israelis do.

Osama bin Laden, the millionaire Saudi exile believed to have master-minded the airliner attacks, defined his motives in a videotaped statement from Afghanistan. I swear to God that America will not live in peace before peace reigns in Palestine, he declared, and before all the army of infidels depart the land of Muhammad, peace be upon him. It was reference to United States military and economic backing for Israel and to the American troops based in Saudi Arabia, the land of Muhammad. But the deeper cause lay in the essence of America itself, in its immense power to project its secular, permissive values into Islamic societies. The seductive American culture of sex, consumerism, and ostentatious wealth tainted the purity of rigid Islam; Americas global economic and military reach seemed to steal Islamic countries capacity for self-determination. In effect, Washington had endorsed the modernist and pluralistic variation of Islamic practice against the narrow intolerance of the new militants. Unwittingly, the United States had taken sides in Islams internal struggle.

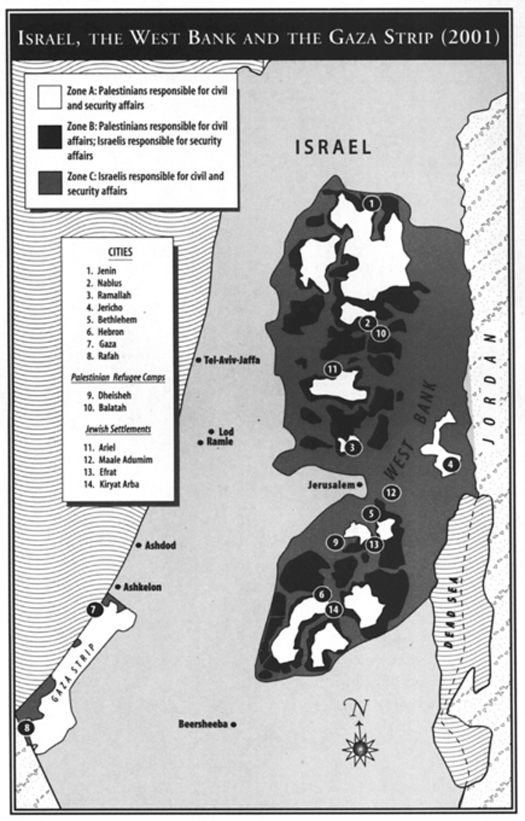

To mobilize against terrorist organizations, Washington courted Arab moderates by frantically pressing Israel and the Palestinians to damp down their violence. As the pall of smoke from lower Manhattan threatened to engulf the globe, however, Israelis and Palestinians conducted business as usual. Israelis sent tanks into parts of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank cities of Ramallah and Hebron, a Palestinian disguised as an Israeli paratrooper killed three Israelis at a bus station, bombs went off, bullets flew, and both sides demonstrated how durable their conflict could be, even as the world braced for a widescale war.

The ongoing Palestinian-Israeli battle was all the worse because a solution had seemed so close at hand.

Those who live the weary history of the Middle East are not easily astonished. Too much hope has been doused in blood. Nothing seems capable of surprising anyone. In the years since this book was first published in 1986, however, reality outran imagination. The implausible became acceptable, the impossible became probable, and the rough landscape of conflict seemed on the verge of a tectonic shift that might have marked a new era.

In 1993 after secret negotiations near Oslo, Israeli and Palestinian leaders signed an accord designed to prepare the ground for a Palestinian state on most of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, in exchange for a pledge of peaceful coexistence with the Jewish state next door. Technically, the agreement was only the first signpost on a long road of hard bargaining and difficult compromise. Spiritually, however, it represented an existential transformation. The two movementsJewish and Palestinian nationalismwere suddenly bonded into an embrace of each others legitimacy. That was new: Neither people had previously acknowledged the others rightful existence as a nation on the narrow strip of land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. A mere meeting between an Israeli and a leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization would have been against the law for the Israeliand against the law of self-preservation for the Palestinian. The change was momentous, but it brought no euphoria. At the signing ceremony in the White House Rose Garden, President Bill Clinton had to nudge the old warrior Yitzhak Rabin, Prime Minister of Israel, toward a hesitant handshake with his opposite number, Yasir Arafat, Chairman of the PLO. Rabin wrinkled his nose as if he were reaching out to touch something vile. Nevertheless, the handshake happened, and the conflict turned a corner. Rabin, Arafat, and Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres won the Nobel Prize for Peace the following yeartoo soon, as it turned out.