First published in the United States and the United Kingdom in hardcover in 2016 by

Overlook Duckworth, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

NEW YORK

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales please contact sales@overlookny.com ,

or to write us at the above address.

LONDON

30 Calvin Street

London E1 6NW

www.ducknet.co.uk

For bulk and special sales please contact ,

or write to us at the above address.

Copyright Michael Wesley 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-4683-1345-1

RESTLESS

CONTINENT

WEALTH, RIVALRY, AND

ASIAS NEW GEOPOLITICS

MICHAEL WESLEY

The essential road-map

for a region in transition

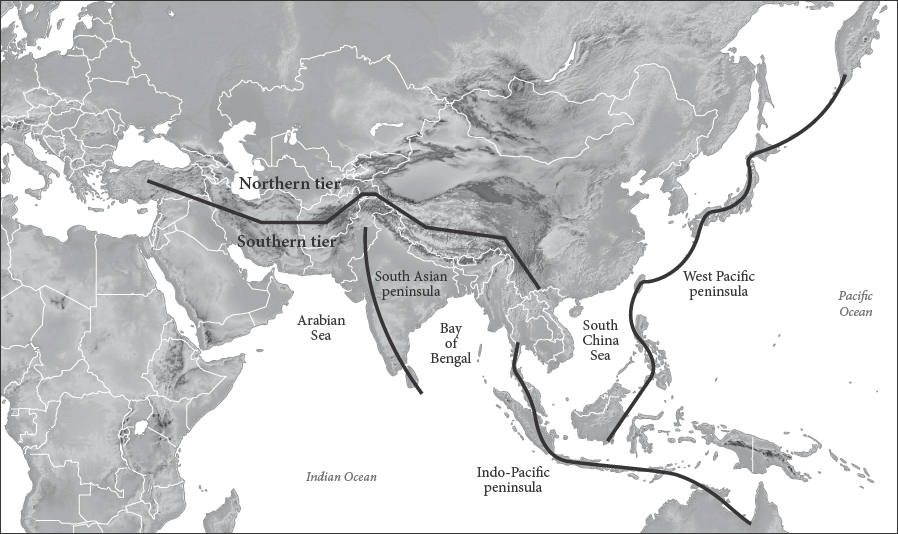

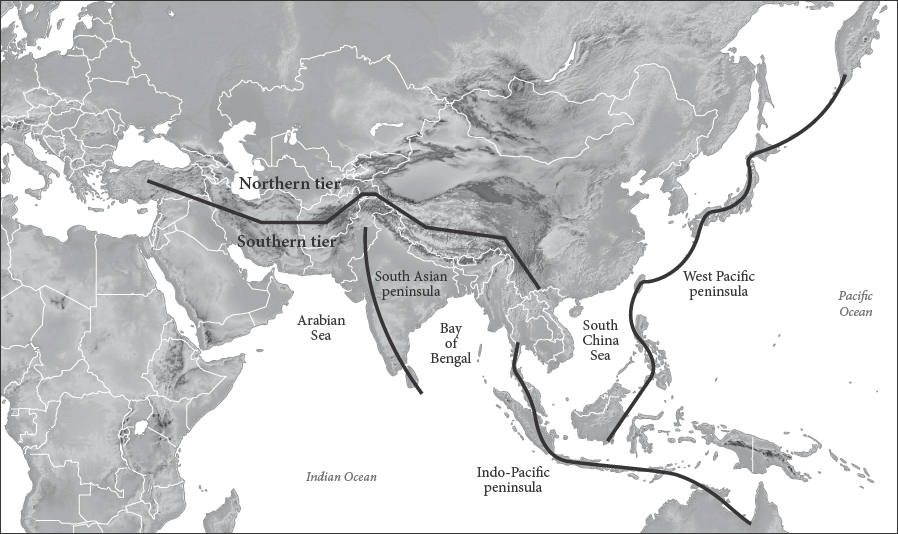

T he world has never seen economic development as rapid or significant as Asias during recent decades. Home to 60% of the worlds population, this restless continent will soon produce more than half of the worlds economic output and consume more energy than the rest of the globe combined.

But surprisingly little hard thinking has been done about the future of Asia. Michael Wesleys Restless Continent is the first book to examine the economic, social, political, and strategic trends across the worlds largest continent, presenting a modern-day roadmap for thinking about not only Asias future, but also how it affects the entire world.

Wesley is one of the worlds leading experts on Asian and international affairs and examines the psychology of countries becoming newly rich and powerful, and explores the corridors of bloodthe geography and politics of conflicts and he makes a case about how to avert a plunge into dispute, or even war.

There is therefore no more important challenge to policymakers, academics, and the public than understanding the drivers of Asias new geopolitics. These are the subjects of Restless Continent.

Only the passing of time will tell whether it was an act of decisive resolve or a gesture of impotence. As dawn broke over the waters of the South China Sea, at 6:40am on Tuesday, October 27, 2015, the USS Lassen, a guided missile destroyer, entered the waters within 12 nautical miles of the disputed Mischief and Subi Reefs. The sail-through had been long-planned and much anticipated. Some six months earlier, Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter had announced that the US Navy would assert its right to freedom of navigation close to those reefs, as part of a deepening dispute with China over the legal status of the South China Sea. Since the 1940s governments of Chinaboth the Nationalist regime now exiled to Taiwan as well as the Peoples Republichave claimed most of the South China Sea as sovereign territorial waters. Their claims have been disputed by other states bordering the Sea who assert their own, more limited territorial claims; as well as by the United States and some of its allies who claim the Sea is an international waterway according to international law. What gave such significance in 2015 to a relatively regular maritime patrol by a US warship was Chinas rapid conversion of eight low-lying reefs and rocks in the Spratley Islands group into artificial islands with dredged sand and concrete. The plain-speaking head of US Pacific Command, Admiral Harry Harris, had proclaimed in early 2015 that by constructing more than four square kilometers of artificial landmass, Beijing had constructed a great wall of sand in the crucial international shipping thoroughfare. At stake was not just the constructions themselves, but what China could put on them. One artificial island had a runway large enough to accommodate the largest warplanes in the Chinese arsenal; others could conceivably host settlements, missiles, and troops.

The Chinese response to the Lassens sail-through was fast and shrill. Vice Foreign Minister Zhang Yesui summoned American Ambassador Max Baucus for an official dressing down over the United States extremely irresponsible actions. An ensuing statement by the Chinese Foreign Ministry made sure there was little chance of misinterpretation: The actions of the US warship have threatened Chinas sovereignty and security interests, jeopardized the safety of personnel and facilities on the reefs and damaged regional peace and stability. The next day, an editorial in the Global Times, one of the Chinese Communist Partys more nationalist mouthpieces, warned, Chinais not frightened to fight a war with the US in the region, and is determined to safeguard its national interests and dignity. As if to back up the Global Times threat, two PLA Navy warships, the Taizhou and the Lanzhou, were dispatched to the vicinity of the Spratley Islands with orders to enforce Chinas sovereignty and deter any further illegal activity. For its part, the United States was also quick to respond. In China on a pre-planned official visit, Admiral Harris spoke with customary clarity to a forum at Peking University: Weve been conducting freedom of navigation operations all over the world for decadesthe South China Sea is not, and will not, be an exception.

As recent Sino-American confrontations go, the Lassen incident looks relatively minor. The risk of serious conflict between the two nuclear-armed powers appeared much more likely in March 1996, when a US aircraft carrier battle group sailed into the Taiwan Straits as a warning to Beijing to desist from aggressive missile tests and naval exercises intended to intimidate historic elections in Taiwan. Or again five years later when a Chinese fighter jet collided with a US EP-3 surveillance aircraft, resulting in a tense stand-off as Beijing refused to release the American plane and crew, which had emergency landed on Hainan Island. What makes the Lassen incident so much more significant are the stakes involved. How and when the United States asserts freedom of navigation and the manner in which China counters by asserting its claimed sovereign imperatives is about so much more than the status of a few partially-submerged rocks and reefs or even one of the worlds most crucial shipping thoroughfares. It is, at base, a contest over primacy in Asia.

Primacy is a word in increasingly regular usage in recent years. This is significant because it is a word that lapses into disuse when it is assumed and uncontested, but it emerges from the shadows when it is under contention. Primacy is essentially the risk-management strategy of every great power in history. As historys great powers have risen and matured, their interests have expanded and evolved, and without exception, each has prioritized the ability to shape the behavior and tolerances of less powerful states to accommodate the great powers evolving interests. As of this book points out, successive European powers contested for primacy in Asia: the Dutch supplanted the Portuguese, only to be toppled by the British. Cultural solidarity and geopolitical alignment dont matter in primacy contests, as the United States demonstrated as it slowly and methodically undermined British primacy in Asia during the early 20th century, and consciously built its own primacy on the foundations laid by Britain. Real primacy is effortless: the less coercion or co-option the great power needs to bend other states to its will, the greater and more complete is its primacy. Different great powers have used different means to achieve primacy: economic dynamism, ideologies, hierarchic relationships, shared interests, institutions and rules. Each great power in history has chosen the terms and means of its own primacy according to what international conditions will best allow it to preserve and extend its own power.