In the writing of my memoirs and the story of a very trying period of history, I have received invaluable aid and suggestions from many people. A vast amount of research of my personal papers and documents was necessary in my efforts to achieve a true and accurate picture.

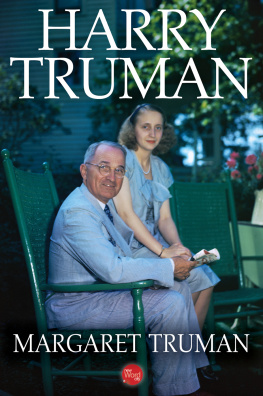

I owe a great debt of gratitude to Mrs. Truman, on whose counsel and judgment I frequently called.

I wish to express my special thanks to many members of my administration who took time to go over with me various phases of the past in which they had a part: Dean Acheson, General of the Army George C. Marshall, Samuel I. Rosenman, John W. Snyder, Rear-Admiral Sidney Souers, Rear Admiral Robert L. Dennison, W. Averell Harriman, General of the Army Omar Bradley, Charles F. Brannan, Charles Sawyer, Philip B. Perlman, Thomas E. Murray, Stanley Woodward, John Steelman, Charles Murphy, Major General Robert B, Landry; as well as Oscar Chapman, Gordon Dean, J. Howard McGrath, Clark Clifford, Edwin W. Pauley, and Judge Caskie Collet.

To Dean Acheson and Samuel I. Rosenman, who painstakingly read and criticized my manuscript, I wish to convey my special gratitude.

During the past two years, David M. Noyes and William Hillman were constantly at my side, helping me to assemble and edit this work. With their collaboration, this book has been made possible. To Dave and to Bill I can only say a thousand times, thank you.

To Professor Francis E. Heller of Kansas University I wish to express my sincere appreciation for the invaluable service he rendered. Among those who also helped with historical research during some periods was Professor Morton Royse.

A very heavy burden fell on my personal staff during the writing and rewriting of these memoirs, and I wish to acknowledge with thanks the devoted work of Mr. Eugene Bailey, Miss Rose Conway, and Miss Frances Myers.

I have used some passages from Mr. President by William Hillman (Farrar, Straus & Young) for inclusion in my memoirs as part of the historical record.

H. S. T.

I have often thought in reading the history of our country how much is lost to us because so few of our Presidents have told their own stories. It would have been helpful for us to know more of what was in their minds and what impelled them to do what they did.

The presidency of the United States carries with it a responsibility so personal as to be without parallel.

Very few are ever authorized to speak for the President. No one can make decisions for him. No one can know all the processes and stages of his thinking in making important decisions. Even those closest to him, even members of his immediate family, never know all the reasons why he does certain things and why he comes to certain conclusions. To be President of the United States is to be lonely, very lonely at times of great decisions.

Unfortunately, some of our Presidents were prevented from telling all the facts of their administrations because they died in office. Some were physically spent on leaving the White House and could not have undertaken to write even if they had wanted to. Some were embittered by the experience and did not care about living it again in telling about it.

As for myself, I should like to record before it is too late, as much of the story of my occupancy of the White House as I am able to tell. The events, as I saw them and as I put them down here, I hope may prove helpful in informing some people and in setting others straight on the facts.

No one who has lived through more than seven and a half years as President of the United States in the midst of one world crisis after another can possibly remember every detail of all that happened. For the last two and a half years, I have checked my memory against my personal papers, memoranda, and letters and with some of the persons who were present when certain decisions were made, seeking to recapture and record accurately the significant events of my administration.

I have tried to refrain from hindsight and afterthoughts. Any schoolboy s afterthought is worth more than the forethought of the greatest statesman. What I have written here is based upon the circumstances and the facts and my thinking at the time I made the decisions, and not what they might have been as a result of later developments.

That part of the manuscript which could not be physically included in the two volumes of the memoirs, I shall turn over to the Library in Independence, Missouri, where it will be made available to scholars and students of history.

For reasons of national security and out of consideration for some people still alive, I have omitted certain material. Some of this material cannot be made available for many years, perhaps for many generations.

In spite of the turmoil and pressure of critical events during the years I was President, the one purpose that dominated me in everything I thought and did was to prevent a third world war. One of the events that has cast a shadow over our lives and the lives of peoples everywhere has been termed, inaccurately, the cold war.

What we have been living through is, in fact, a period of nationalistic, social, and economic tensions. These tensions were in part brought about by shattered nations trying to recover from the war and by peoples in many places awakening to their right to freedom. More than half of the world s population was subject for centuries to foreign domination and economic slavery. The repercussions of the American and French revolutions are just now being felt all around the world.

This was a natural development of events, and the United States did all it could to help and encourage nations and peoples to recovery and to independence.

Unhappily, one imperialistic nation, Soviet Russia, sought to take advantage of this world situation. It was for this reason, only, that we had to make sure of our military strength. We are not a militaristic nation, but we had to meet the world situation with which we were faced.

We knew that there could be no lasting peace so long as there were large populations in the world living under primitive conditions and suffering from starvation, disease, and denial of the advantages of modern science and industry.

There is enough in the world for everyone to have plenty to live on happily and to be at peace with his neighbors.

I believe, as I said on January 15, 1953, in my last address to the American people before leaving the White House: We have averted World War III up to now, and we may have already succeeded in establishing conditions which can keep that war from happening as far ahead as man can see.

H . S . T .

Independence, Missouri

Within the first few months, I discovered that being a President is like riding a tiger. A man has to keep on riding or be swallowed. The fantastically crowded nine months of 1945 taught me that a President either is constantly on top of events or, if he hesitates, events will soon be on top of him. I never felt that I could let up for a single moment.

No one who has not had the responsibility can really understand what it is like to be President, not even his closest aides or members of his immediate family. There is no end to the chain of responsibility that binds him, and he is never allowed to forget that he is President. What kept me going in 1945 was my belief that there is far more good than evil in men and that it is the business of government to make the good prevail.