Copyright 2017 by John F. Pfaff

Published in the United States by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, 15th floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special. markets@perseusbooks.com.

Designed by Linda Mark

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pfaff, John F., author.

Title: Locked in : the true causes of mass incarcerationand how to achieve

real reform / John Pfaff.

Description: New York : Basic Books, [2017] | Includes bibliographical

references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016037701| ISBN 9780465096916 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780465096923 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Imprisonment--United States. | Criminal justice,

Administration ofUnited States. | CorrectionsUnited States.

Classification: LCC HV9471 .P449 2017 | DDC 365/.973dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016037701

E3-20170131-JV-PC

To those impacted by our flawed criminal justice system. And to those working together toward reform.

D ONALD T RUMPS SURPRISE VICTORY OVER H ILLARY C LINTON on November 8, 2016, upended most peoples expectations of what public policy in this countryincluding criminal justice reformwould look like over the next four years, if not the next forty. Clinton had met with Black Lives Matters leaders and laid out a proposal for end-to-end reform of the criminal justice system; Donald Trump had surrounded himself with tough-on-crime advisers including Rudolph Giuliani and spoken favorably of now-discredited aggressive crime control policies like stop-and-frisk.

Yet that fateful Tuesday night was not a defeat for criminal justice reform. Far from it. As voters elected Donald Trump, they also passed a large number of criminal justice referendumsmany of them (although, importantly, not all) reform-orientedand voted out several tough-on-crime prosecutors in red and blue states alike. Consider Oklahoma: while Trump got 65 percent of the vote, the state also passed State Questions 780 and 781, which downgraded many drug possession and property offenses from felonies to misdemeanors, and required that the savings from the resulting reduced prison costs be directed to mental health and drug treatment programs.

Within days, dozens of articles appeared, all making the same point: somehow, surprisingly, criminal justice reform seemed poised to survive even under a Trump administration. Well, yes and no. Reform efforts will continue. Many voters, even those who voted for Trump, still seem to support cutting back prison populations, despite crime rising somewhat in 2015 and despite Trumps rhetoric. One point I make in this book is that the federal government has little control over criminal justice reform, which is predominantly a state and local endeavor. As long as local voters favor reform, it will move ahead. And Election Day 2016s results suggest that many voters do.

At the same time, reformers still dont understand the root causes of mass incarceration, so many reforms will be ineffective, if not outright failures. Election Night offers a clear case study. Not all the successful ballot questions on criminal justice matters were reform-oriented; some were aimed at making laws harsher. An important split emerged. The reform questions focused on nonviolent drug and property crimes. The tougher-on-crime referendums, however, dealt with violent offenses and included proposals to speed up the death penalty process (passed in red Oklahoma and blue California) and a victims-rights law called Marsys Law that is so expansive that even prosecutors opposed it.

These results fit a common pattern in criminal justice reform, which for years has been premised on the idea that we can scale back our prison population primarily by targeting low-level, nonviolent crimes. A major theme of this book is that this is wrong: a majority of people in prison have been convicted of violent crimes, and an even greater number have engaged in violent behavior. Until we accept that meaningful prison reform means changing how we punish violent crimes, true reform will not be possible.

A similar misperception shapes the debate over private prisons. Such institutions receive significant attention and criticism, but their overall impact on prison growth is slight: only about 8 percent of prisoners are in private prisons, and there is no evidence that states that rely on private prisons are any more punitive than those that do not. So although private prison firms saw their stock prices soar in the aftermath of Trumps victoryand even if more prisoners are sent to private prisons in the coming yearsreformers attention should aim at individuals who play a much bigger role in supporting punitive policies and driving incarceration trends, including state and county politicians with prisons in their districts, and at prison guard unions. Yet these public-sector groups continue to face little scrutiny. In short, the state and local commitment to reform may endure. But because that commitment remains focused on the relatively unimportant factors behind prison growth, it continues to ignore the most important causes of this national shame.

John Pfaff

N OVEMBER 2016

Even repressive regimes like Russia and Cuba have fewer people behind bars and lower incarceration rates.

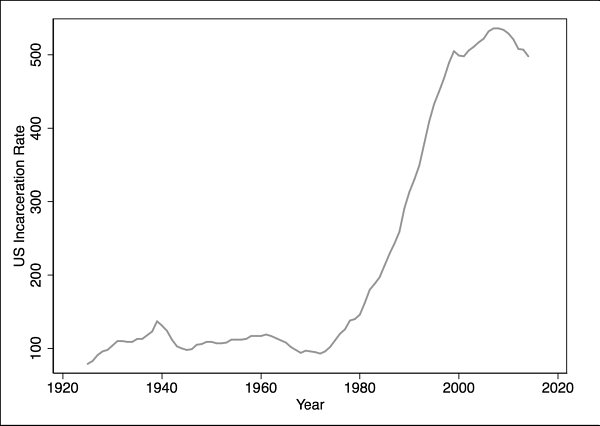

It wasnt always like this. Just forty years ago, in the 1970s, our incarceration rate was one-fifth what it is today. It was comparable to that of most European countries, and it had been relatively stable all the way back to the mid- to late 1800s. It was, in short, nothing out of the ordinary.

In fact, the prison boom started so suddenly that it caught most observers by surprise. In 1979, a leading academic wrote that the incarceration rate would always remain fairly constant, because if it climbed too high, state governments would adjust policies to push it back down.

Figure 1 US Incarceration Rates, 19252014

Source: Patrick A. Langan, John V. Fundis, Lawrence A. Greenfield, and Victoria W. Schneider, Historical Statistics on Prisoners in State and Federal Institutions, Year-End 1925-1986, US Department of Justice, December 1986, accessed October 11, 2016, www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/hesus5084.pdf, and US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Data Collection: NPS Program, www.bjs.gov/index.ctm?ty=dcdetail&iid=269.

Remarkably, these numbers understate how many people are locked in prisons and jails each year. In 2014, approximately 2.2 million people were in state or federal prisons at some point, and perhaps as many as 12 million passed through county jails.but clearly somethingor a lot of thingschanged, and our prison populations took an unprecedented turn.

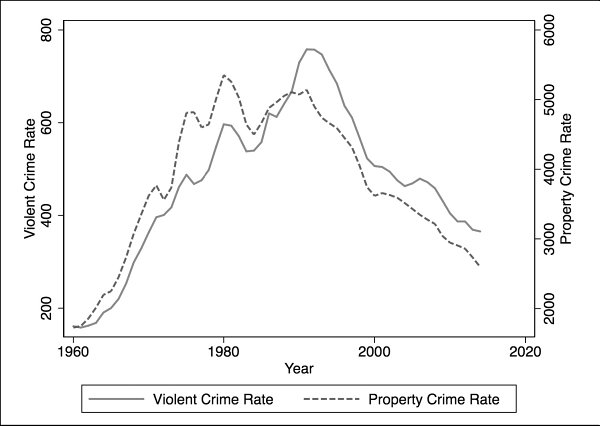

Figure 2 Crime Trends, 19602014