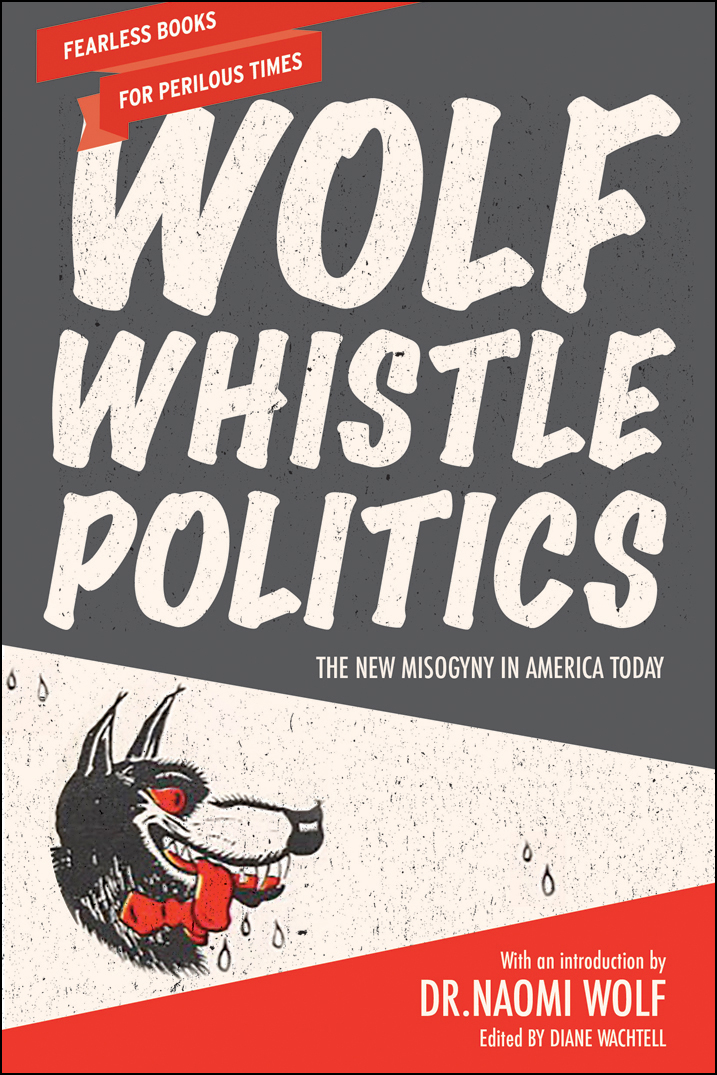

Compilation 2017 by The New Press

Individual pieces 2017 by individual contributors

Page 159 constitutes an extension of this copyright page

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to:

Permissions Department, The New Press,

120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2017

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

ISBN 978-1-62097-353-0 (e-book)

CIP data is available

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Book design and composition by dix!

This book was set in Electra

Printed in the United States of America

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

Dr. Naomi Wolf is the author of eight bestselling nonfiction books, including The Beauty Myth and Vagina: A New Biography. She recently earned a doctorate from the University of Oxford. A former Gore advisor, Wolf is CEO of DailyClout, a media company that makes tech tools and content for democracy, and the author of the forthcoming Outrages.

When I published a book called Vagina four years ago, arguing that targeting the genitals and sexuality of women was a political ploy, and that women needed to defend their sexualityand even their genitalsovertly in order to be a potent political force, the topic was seen to be outr, and I was chastised for introducing womens reproductive organs into politics. The vagina has since made many rather shocking appearances in the political fray. Donald Trump and Billy Bush talked about grabbing womens vaginas without permission. The New York Times ran the word pussy on the front page for the first time in its history. And when a woman with a national platformFox Newss Megyn Kellycalled Donald Trump out on broadcast television, like a metronome, Trump invoked for viewers the image of Ms. Kellys bleeding vagina. This attack was meant to silence Kelly, as attacks on womens vaginasindeed the mere invocation of that shameful, silencing termalways have been.

But on the Mall in Washington the day after Donald Trumps inauguration, you couldnt shut nearly a half million women up about their genitals, their reproductive organs, and the politics of defending and attacking them. A groundswell of furious, mainstream-as-can-be women carried signs that were newly combative and explicit: This Pussy Grabs Back was one, and If I wanted the government in my uterus, Id fuck a congressman was another. The icon of a uterus with fallopian tubes was on many signs; on one, the organ itself was giving Trump the finger. You really like it? No, I really dont was yet another.

In DC, New York, Seattle, London, New Delhi, and Christchurch, womenand the men who support themflowed into a vast, iconic river of pink pussyhats1.7 million of these were knitted by the Pussyhat Project and worn at protests around the country and the world. Women of every background and age showed up wearing an item symbolizing a very personal part of their bodies, screaming mad in defense of their genitals, their wombs, their vital organs. Sick of sexual abuse. Sick of loss of reproductive control. Sick of being degraded. They even brought their kids to the marches; todays rage was going to infect the next generation.

This huge response was a result, I believe, of womens awareness of a newly brutal form of political engagement, an overtly misogynist approach, aptly described by former Texas state senator Wendy Davis (of filibuster fame) in a speech she gave at Princeton in 2015 as Wolf Whistle Politics.

What accounts for such explicit, in-your-face sexism at this moment in time? I would hazard that its the prospect of women in power at last. The presidential race clearly inflamed this new brutality. But it was just tinder that has been ready for some time to set a bonfire ablaze. The year 2016 was the year in which gender issues exploded all over the American political map. Everywhere you looked there was evidence of a gender crisis: gendered hope and gendered hostility; gendered rage, violence, and fear; pussy grabbing and invocations of Seneca Falls.

Even in his manic, tantrum-y chaos, Candidate Trump inhabited the current moment in America in which men and women really live: our world of social media impulsivity, nonstop porn, shock jocks, celebrity worship, and raw emotional battle. He particularly called out to the serious divides between haves and have-nots, both male and female. It all erupted continually during the last presidential campaign in America, and the shards poked awkwardlyand at times painfullythrough what had been the last fragile veneers of polite traditional political discourse.

The essays collected in this book assemble into a legible mosaic the many fragments of that eruption. Yes, of course, the presidential race was where most of the action was, but this volume pulls the lens back, broadening the discussion to include a wide range of women and issues in the openly bigoted and sexist public sphere today.

In her Princeton speech, Wendy Davis likened wolf whistle politics to the coded signaling of dog whistle politics, which scholar Ian Haney Lopez used to characterize racist political pandering, as exemplified by Richard Nixons infamous Southern strategy. But where dog whistling is covert and happens at a pitch that cant be heard by many, wolf whistling is right there in your face. Wolf whistling is an undisguised lasciviousness that condones and informs, Davis asserts, the sexualized nature in which women candidates and womens issues are often framed. Women candidates, as Davis notes, are viciously and openly sexualized with impunity. She talks about how she was targeted with sexualized imagery to demean her during her senatorial bid. As she points out, the ploy works, so why stop?

At this moment in history, Daviss term can easily be expanded to include the play of overt and violent misogyny throughout public life, including women of all kinds: voters, marchers, spokeswomen, workers, medical patients, moms, and other everyday female leaders, political and not. Though the Trump/Clinton matchup in 2016 was the catalyst, like Betty Friedans problem that has no name in the 1960s, and Susan Faludis backlash in the 1990s, the concept of wolf whistle politics allows us to discern the contours of a contemporary constellation we may not have perceived before. If we trace the thread of vicious, angry, and sexualized sexismas opposed to the more polite, condescending sexism of the first decade or so of the twenty-first centurywe can use the concept of wolf whistle politics to smoke out and name a whole gamut of tactics that have somehow, appallingly, made their way back to Americas center stage.