Praise for the book

A remarkable compendium. The topics Arora tackles hereIndias formidable caste, class, and gender inequalities, and how its leaders, writers, and thinkers have engaged with themhave been tackled before, but mostly in dense academic volumes. Whats unique here is Aroras seamlessly accessible and personable language, rich with autobiographical context, so we feel that the author has a stake in what he speaks of, above all, as an engaged citizen. From ancient scriptures to Dalit literature, reservations to violence against women, Arundhati Roys controversial views on Gandhi and Ambedkar to Perry Andersons controversial views on Indian history, these essays are essential reading for anyone who wants to understand contemporary India.

Arun P. Mukherjee , Professor Emerita, York University.

Namit Arora writes with envy-inspiring clarity and erudition about the central role in our lives of the many random inequalities we begin life with, such as class, gender, and, especially important in the Indian context, caste. This brilliant book is an immensely useful corrective to the conservative notion that people get more-or-less what they deserve, based on their own merit and hard work. Read it. If nothing else, it will surely soften your attitude toward the disadvantaged in our midst, which is never a bad thing.

S. Abbas Raza , Founding Editor, 3 Quarks Daily.

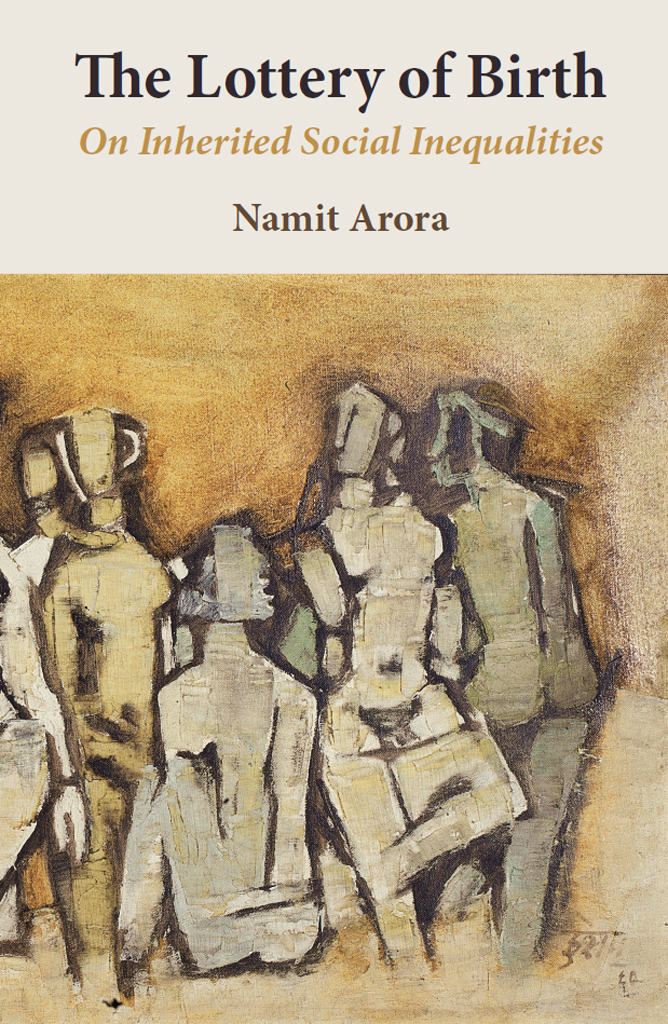

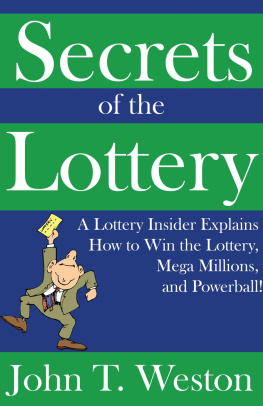

The Lottery of Birth

On Inherited Social Inequalities

Namit Arora

First Edition April 2017

copyrightNamit Arora & Three Essays Collective 2016

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978-93-83968-19-0

B-957 Palam Vihar, GURGAON (Haryana) 122 017 India

Tel: 91-124 236 9023, +91 98681 26587, +91 98683 44843

To my parents,

Shrinath Arora and Lata Arora,

for giving me a childhood most can only dream of.

Contents

On Omprakash Valmikis classic autobiography

On Ajay Navarias short stories

On A. Revathis autobiography

A brisk overview of the caste system: its origins, spread, persistence, and some historical attitudes and debates

Making sense of Indian democracys attempts to combat inequalities of birth, especially via reservations

Many have written about the unearned privileges of race and gender. What does the privilege of caste look like?

Why the Bhagavad Gita is an overrated text with a deplorable morality at its core

On how caste patriarchy in urban India hijacks and distorts the reality of gender violence

On English in India and the linguistic hierarchies of colonized minds

For our learning, natural talents, and labor, what rewards and entitlements can we fairly claim?

On Ambedkars place in the Indian imagination, and why he hasnt received his due from upper-caste Indians

On Arundhati Roys introduction to Dr. BR Ambedkars classic text, Annihilation of Caste

The highs and lows of identity politics, and why despising it is no smarter than despising politics itself

On Perry Andersons The Indian Ideology , focusing on Indian nationalism from the colonial era to the present

Introduction

The idea of equality may be as old as the human imagination. We remain in thrall to it, even as we continue to argue over what sort of equality we want: of rights, opportunities, results? The most foundational of these, equality of rights , is perhaps something that most people today agree ona rather wondrous thingas evidenced by their broad support for equal political and civil rights, or formal equality before the law, for all.

Most people today might also agree that equality of results (meaning equality of socioeconomic outcomes) is not a worthy goal. Theyre disenchanted with far-left politics. Achieving equality of results in individual lives, it appears, comes with other undue costs, such as repressive curbs on liberty and a devaluing of the natural differences between peoplea loss both to society and to individual flourishing.

But the same people may also agree that the results should not be spread out too wideout of a concern for social stability, if not also for justice and individual flourishing. Most people seem to want the results to fall within a reasonable spread, though how wide the spread ought to be, around what medianand what moral arguments could justify itremains an area of lively debate and a fault line in our politics today. Yet, in recent decades, wealth distribution has grown more extreme even as an unprecedented number of people have emerged out of abject poverty.

What about equality of opportunity ? This refers to the idea of a level playing field where people compete with others on equal terms, without being disadvantaged by bias, discrimination, or socioeconomic disability. Most people might agree that this is not only good but a necessary goal. With genuine equality of opportunity, the accident of ones birth in any particular social stratum would cease to be a major predictor for outcomes in ones lifeor at least much less than it is today, especially in Indiaand there would be high social mobility, with people moving both up and down based on a fair set of rules.

But people often dont agree on when and where equality of opportunity is lacking, or how best to increase it. Indeed, a great blindness, apathy, and doublethink often descend on people when discussing this topic, especially if they are ahead. Furthermore, how are we to achieve equality of opportunity while permitting inequality of results? Wouldnt those who are ahead also invest their material and cultural capital in keeping their progeny ahead? Wouldnt they find creative ways to pull the ladder up behind them and to lower it selectively only for their own people, undermining both equality of opportunity and social mobility?

Not surprisingly, equality of opportunity remains a formidable battleground and a major goal of social justice movements. What are the psychological, social, and ideological barriers to advancing the equalities of opportunity and results everywhere, including in India? Ill briefly discuss three such barriers in this introduction, leaving a fuller exposition to emerge from other essays. These barriers include (a) our psychological disposition to believe in a just world, (b) our social organization in moral communities, and (c) the ideology of the dominant class. All three are intertwined and reinforce each other to discourage an egalitarian order.

The Belief in a Just World

A leading ideological fiction of our age is that worldly success comes to those who deserve it. Per this fiction, the smarter, more talented and disciplined men and women, with some unfortunate exceptions, come out ahead of the rest and morally deserve their material rewards in life. The flip side of this belief is of course that, with some unfortunate exceptions, those who find themselves at the bottom also morally deserve their lot for beingthe conclusion is inescapableneither smart nor talented nor disciplined enough.