Contents

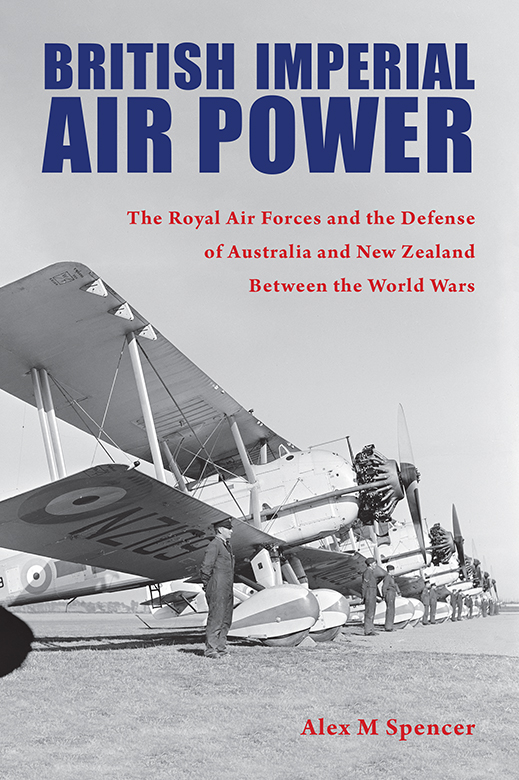

BRITISH IMPERIAL

AIR POWER

PURDUE STUDIES IN AERONAUTICS

AND ASTRONAUTICS

James R. Hansen, Series Editor

Purdue Studies in Aeronautics and Astronautics builds on Purdues leadership in aeronautic and astronautic engineering, as well as the historic accomplishments of many of its luminary alums. Works in the series will explore cutting-edge topics in aeronautics and astronautics enterprises, tell unique stories from the history of flight and space travel, and contemplate the future of human space exploration and colonization.

RECENT BOOKS IN THE SERIES

A Reluctant Icon: Letters to Neil Armstrong

by James R. Hansen

John Houbolt: The Unsung Hero of the Apollo Moon Landings

by William F. Causey

Dear Neil Armstrong: Letters to the First Man from All Mankind

by James R. Hansen

Piercing the Horizon: The Story of Visionary NASA Chief Tom Paine

by Sunny Tsiao

Calculated Risk: The Supersonic Life and Times of Gus Grissom

by George Leopold

Spacewalker: My Journey in Space and Faith as

NASAs Record-Setting Frequent Flyer

by Jerry L. Ross

BRITISH IMPERIAL

AIR POWER

The Royal Air Forces and the Defense

of Australia and New Zealand

Between the World Wars

Alex M Spencer

Purdue University Press

West Lafayette, Indiana

The funding and support of the author by the Smithsonian Institution

made the research and writing of this book possible.

Copyright 2020 by Smithsonian Institution. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the Library of Congress.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-940-3

epub ISBN: 978-1-55753-942-7

epdf ISBN: 978-1-55753-941-0

Cover image: Courtesy of the National Library of New Zealand.

To my wife, Mary: her love and support was invaluable

and helped sustain me throughout the production of this book

CONTENTS

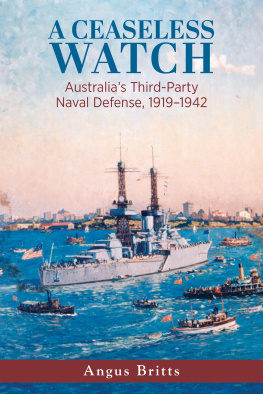

At approximately 10 oclock on the morning of February 19, 1942, the Imperial Japanese Navy and Army Air Force opened a coordinated attack on Darwin, Australia. More than 188 aircraft launched from four aircraft carriers and fifty-five land-based bombers destroyed shipping and the harbors transport and military infrastructure. Nearly an hour later, a subsequent raid by Japanese army bombers attacked the Royal Australian Air Force base at Parap, destroying numerous aircraft and base facilities. From February 1942 through November 1943, the Japanese conducted sixty-four more air attacks on Darwin. In addition, the Japanese carried out similar strikes on Townsville, Katherine, Windham, Derby, Broome, and Port Hedland. Even though Australia and New Zealand joined the war in 1939, their respective air forces were ill prepared at the outbreak of war with Japan because the majority of their military assets had been sent to the Middle East in support of British operations.

The study of the development of the air defense of Great Britains Pacific Dominions demonstrates the difficulty of applying the emerging military aviation technology to the defense of the global British Empire during the interwar years. It also provides insight into the changing nature of the political relationship between the Dominions and Britain within the British imperial structure. At the end of World War I, both Australia and New Zealand secured independent control As a result, the empires air services spent the entire interwar period attempting to create a comprehensive strategy in the face of these handicaps.

For many aviation advocates during the interwar period, the airplane represented a panacea to the imperial defense needs. They always prefaced their arguments with the word potential. The airplane could potentially replace the navy; it could potentially provide substantial savings in defense expenditure; it could potentially move rapidly to threatened regions; and it could potentially defend the coast from attack or invasion. For all of these claims, there was no supporting empirical data. In short, aviation advocates offered the air force as a third option for the empires defense, in an attempt to replace the Royal Navy and British Army.

At first glance, it is easy to accuse Britain and its Dominions of willful neglect of their armed forces during the interwar years. As early as 1934, however, Britains military and political leadership understood the threat to peace and stability that Germany, Italy, and Japan represented, but the empire faced a difficult strategic problem in having a military force structure inadequate to defend the vast worldwide imperial possessions and the inability to pay for the needed expansion. The General Staff, to the best of their ability, began to implement the necessary steps required to expand their military forces to meet these threats and particularly directed funds to expand their respective air forces. Although the leadership was much criticized in the postwar period, their diligence paid dividends as early as 1940, when Britains aircraft industry outpaced German aircraft production, and by 1944, the air forces of the British Empire experienced an expansion well beyond the perceived needs contemplated by the military and political leadership during the interwar period. Many of the policies adopted and implemented by the RAF, RAAF, and RNZAF during the interwar years made this expansion possible.

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) experienced a fourfold increase from seventeen operational squadrons in 1939 to seventy-one in 1944. This included operational squadrons in Britain comprised of four heavy bomber, three medium/attack bomber, seven fighter, and one flying boat squadrons; in the Middle East there were two medium/attack bomber and two fighter squadrons; and in the Pacific the RAAF fielded a force of fifty-five squadrons that included fourteen fighter, fifteen attack/medium bomber, eleven transport and liaison, eight seaplane, and seven heavy bomber squadrons. In addition, more than 4,000 Australian pilots, air crew members, and mechanics served in Royal Air Force (RAF) units throughout the war.

Likewise, the smaller Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) sustained a similar expansion from four prewar squadrons to thirty-three squadrons by 1944. By the end of the war, New Zealand had based eight squadrons overseas, including seven in Britain, consisting of two fighter, three attack/medium bomber, one heavy bomber, and one flying boat squadrons, as well as one fighter squadron stationed in West Africa. Twenty-six RNZAF squadrons served in the Pacific theater and included thirteen fighter, six attack/medium bomber, two flying boat, two torpedo, two liaison/transport, and one dive-bomber squadrons that complemented American Army Air Forces, marine, and navy units throughout the entire Solomon Islands campaign.

By the beginning of the World War II, there were essentially two Australian and New Zealand air forces that emerged from the interwar period. One consisted of the units and personnel that served in Britain as part of the Royal Air Force and that fulfilled the Dominions imperial commitments and prewar strategic assumptions. These units were trained, equipped, patterned after, and served alongside other RAF units. These Australian and New Zealand air force units represented the most significant contribution of men and materiel by the two Dominions in Western Europe during the war. Following the North African campaign, no Australian ground unit fought in Europe and only one New Zealand division served in the Italian campaign.