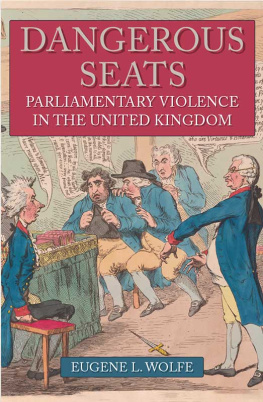

Wolfe - Dangerous Seats

Here you can read online Wolfe - Dangerous Seats full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Amberley Publishing, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Dangerous Seats: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Dangerous Seats" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Dangerous Seats — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Dangerous Seats" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Whether it was brave or foolish for an American political scientist with a background in Russia and Japan to undertake a history of parliamentary violence in the United Kingdom will be left for the reader to decide. It seemed like a good idea when the project began more than a decade ago. What is beyond dispute is that the pages that follow would have been significantly poorer had not the author received extensive help from many quarters.

The debt begins with the published works listed in the bibliography and, especially, the invaluable History of Parliament series, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and the online archives of The Times and The New York Times. Scholars, including Art Cosgrove, Philip Cowley, Emma Crewe, Michael Chwe, Coleman Dennehy, Vic Gatrell, Julian Goodare, Phil Gyford, Tim Harris, Geoffrey Haywood, Maija Jansson, James Kelly, Mark Kishlansky, Gillian MacIntosh, Brid McGrath, Charles McGrath, Mark Ormrod, Derek Patrick, Philip Robinson, Nick Rogers, Philip Salmon, Paul Seaward, Bob Shoemaker, John Stevenson, Richard Toye, David Underdown, Alison Wall and John Walter, kindly responded to a strangers emails with helpful insights, suggestions and advice. The staff of the House of Commons Information Office patiently answered numerous queries. University librarians Lisa Rose-Wiles and Alan Delozier (at Seton Hall) and Jeremy Darrington (at Princeton) helped with access to documents, as did staff at the British Library, the National Library of Ireland, the Library of Congress and the Cobham (Surrey) and Mendham (New Jersey) public libraries. The cover illustration, The dagger scene, or, the plot discoverd, by James Gillray, 1792, is courtesy of Yale Universitys Lewis Walpole Library. Kristen McDonald, at the Library, helped me obtain both that image and most of the artwork in the Plates section. Michael Healy at the Copyright Clearance Center provided guidance on the selection of images. Sammy Sturgess at the History of Parliament assisted with citations. Alastair Mann and an anonymous reviewer provided helpful feedback on sections of the manuscript. Connor Stait at Amberley Publishing patiently helped me bring this book to fruition. Jenny Davis, Hamish Lochhead and Steven Roy at Parkside School educated an outsider in some of the basics of parliamentary politics. None of the above, of course, bears responsibility for any errors, omissions or infelicities in the ensuing pages.

Closer to home, the lads at Old Wokingians FC provided a refuge for a visiting Yank, all the while (largely) resisting the urge to tell him just how rubbish he was at their beautiful game. My mother, Mary Wolfe, and her friend Kittie Beyer pored over candidates for the Plates section. My sons, Levering and Clinton, (mostly) resisted snide comments about what must have seemed a never-ending project. However, by far my greatest debt is to my wife, Cathy. Without her love, support, patience and six-year posting to Kingston upon Thames, the tale that follows surely would have remained untold.

The United Kingdoms parliamentary seats long have been inherently dangerous. Those who have held them over the centuries thereby have risked physical injury from irate monarchs, vexed colleagues, disgruntled soldiers, angry mobs and aggrieved activists. They have endured imprisonment for their parliamentary activity, duels arising out of debate, brawls on the floor, forcible removals from the chamber and personal assaults on the streets. At least twenty-one parliamentarians have died as a result. Threats to seat holders have prompted the expansion of parliamentary privilege and changes to institutional procedure, legislation, public policy and popular opinion. So regularly have political controversies been punctuated by such perils that their history serves as a useful, if rather unusual, window into development of the parliamentary system over the past seven hundred years. Yet the fascinating, incredible, and often faintly absurd story of parliamentary violence in the United Kingdom has yet to be told.

The neglect is surprising and undeserved for parliamentary violence often has been quite consequential. There is a reason Guy Fawkess attempt to blow up Westminster Palace in 1605 is remembered every Fifth of November. Other incidents, though less well known, also have left important legacies. A savage attack on Sir John Coventry for an impertinent 1670 Commons allusion to the kings mistresses prompted a change to the penal code that endured for over a century. A duel between erstwhile cabinet colleagues George Canning and Viscount Castlereagh in 1809 had a lasting impact not only on British politics but also on the shape of the post-Napoleonic European order.

This is a saga of delicious contradictions. Start out with an existential irony: parliament was created to reduce conflict but often has served to foment it; add in lawmakers repeatedly flouting their own laws by seeking to fight duels and elected representatives occasionally being pressured to adhere to popular opinion by baying mobs. Savour the thought of personal violence, often regarded as the instrument of the weak and dispossessed, being employed by some of the most powerful individuals in the kingdom. Six of the fourteen prime ministers in office between 1779 and 1846 fought, or sought to fight, duels.

The denizens of Westminster Palace dominate our story, so much so that unless otherwise specified, the parliament in question is the English/British institution. This is partly because they have been studied more than their cousins in other parliaments. It also may reflect the predilections of the predominant nationality: according to Jeremy Paxman, thuggery is something the English do.

Yet, parliamentary violence hardly has been an English monopoly. The members of the two assemblies absorbed into Westminster, namely the (pre-1707) Scottish and the (pre-1800) Irish parliaments, also were involved in quite a bit of hurly-burly. Often, it was connected to English/British politics, so it makes sense to consider violence in Dublin and Edinburgh along with that in Westminster. By the same token, devolution of power to the Parliament of Northern Ireland a century ago effectively transferred some disorder from Westminster to Belfast, so violence involving those with seats in Stormont should not be ignored. (However, violence in the Irish Republics Dil, although created by those elected to Westminster, is omitted.) The same logic demands scrutiny of the recently devolved Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly, although both seem unsullied by violence, at least so far.

How important, interesting and pervasive parliamentary violence has been depends on how the term is defined. From early on, it has been recognised that parliamentary deliberations should be free from intimidation; force of argument rather than force of arms was to be decisive. Physical threats that might change how members behave politically undermine parliament as an institution. Focusing on such menaces seems to require that violence be construed rather broadly while parliamentary is understood more narrowly.

There is quite a bit of ostensible violence that reaffirms rather than subverts the established political order. Before the monarch travels to Westminster Palace for the State Opening of Parliament, a Member of the House of Commons is sent to Buckingham Palace as a hostage to ensure the sovereigns safe return from her perilous journey. The Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod is then dispatched to summon Members of Parliament (MPs) to listen to the Queens Speech at the bar of the House of Lords. As he approaches the Commons, the doors are slammed in his face to demonstrate the institutions independence. To gain admittance, he strikes the doors with his staff, the marks from which would be seen as evidence of vandalism in a different context.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Dangerous Seats»

Look at similar books to Dangerous Seats. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Dangerous Seats and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.