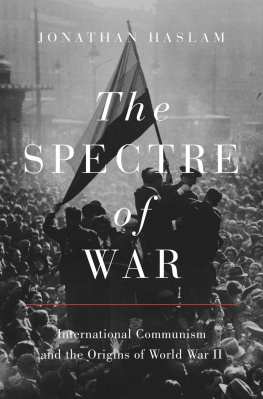

THE SPECTRE OF WAR

PRINCETON STUDIES IN INTERNATIONAL HISTORY AND POLITICS

G. John Ikenberry, Marc Trachtenberg, William C. Wohlforth, and Keren Yarhi-Milo, Series Editors

For a full list of titles in the series, go to https: // press.princeton.edu/series/princeton-studies-in-international-history-and-politics.

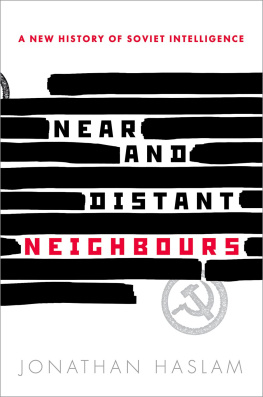

The Spectre of War: International Communism and the Origins of World War II, Jonathan Haslam

Strategic Instincts: The Adaptive Advantages of Cognitive Biases in International Politics, Dominic D. P. Johnson

Divided Armies: Inequality and Battlefield Performance in Modern War, Jason Lyall

Active Defense: Chinas Military Strategy since 1949, M. Taylor Fravel

After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order after Major Wars, New Edition, G. John Ikenberry

Cult of the Irrelevant: The Waning Influence of Social Science on National Security, Michael C. Desch

Secret Wars: Covert Conflict in International Politics, Austin Carson

Who Fights for Reputation: The Psychology of Leaders in International Conflict, Keren Yarhi-Milo

Aftershocks: Great Powers and Domestic Reforms in the Twentieth Century, Seva Gunitsky

Why Wilson Matters: The Origin of American Liberal Internationalism and Its Crisis Today, Tony Smith

Powerplay: The Origins of the American Alliance System in Asia, Victor D. Cha

Economic Interdependence and War, Dale C. Copeland

Knowing the Adversary: Leaders, Intelligence, and Assessment of Intentions in International Relations, Keren Yarhi-Milo

The Spectre of War

INTERNATIONAL COMMUNISM AND THE ORIGINS OF WORLD WAR II

JONATHAN HASLAM

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2021 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Haslam, Jonathan, author.

Title: The spectre of war : international communism and the origins of World War II / Jonathan Haslam.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2021. | Series: Princeton studies in international history and politics | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020035229 | ISBN 9780691182650 (hardback) | ISBN 9780691219110 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: CommunismEuropeHistory20th century. | Social stratificationEuropeHistory20th century. | Propaganda, CommunistEuropeHistory20th century. | EuropePolitics and government20th century. | EuropeForeign relations20th century. | EuropeHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC HX238 .H37 2021 | DDC 940.53/112dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020035229

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Bridget Flannery-McCoy and Alena Chekhanov

Production Editorial: Kathleen Cioffi

Text and Jacket Design: Karl Spurzem

Production: Danielle Amatucci

Publicity: Maria Whelan and Kate Farquhar-Thomsen

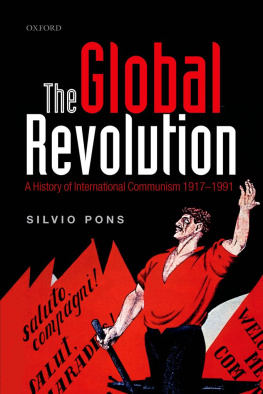

Jacket image: Alfonso Snchez Portela, Proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic, April 14, 1931. Courtesy of Museo Nacional Centro de Arte, Reina Sofa, Madrid, Spain

PREFACE

The world we live in was shaped by the Second World War. Understanding what happened and why still matters. The lessons have still to be learned.

None of us turns to history with an entirely open mind, however. For those of us who were children in the Britain of the early 1950s, the war was still very much a part of our lives and our consciousness. London was still in part a bombed-out city. The massive concrete anti-tank blocks scattered along stretches of the south coast were still visible. Every so often beaches had to be closed because unexploded bombs had been uncovered by the tide. Our aged neighbours still had an air-raid shelter under the garden rockery. The lead-lined windows in my bedroom had been partially blown in by a blast of spare ordnance dropped by the Luftwaffe to lighten the load before its bombers made the sea-crossing to occupied Europe. Teachers at school carried their military rank; one was absent for days on end from bouts of malaria. We read war comics in black and white; the Germans were our enemies. Granny, who had worked as a volunteer in the London auxiliary fire brigade (191618), refused to discuss the last war, or the one before that or, indeed, the South African War, where she had lost a brother. Grandpas hearing was bad from the big guns and he had been blinded for nearly a year from mustard gas in the Great War. Yet somehow he hated only the French. My great aunt at Belsize Park regularly rehearsed for us what had happened when a V-1 rocket appeared out of nowhere and the buzz suddenly stopped, everyone waiting for the inevitable explosion. An uncle remembered trying to stop Belgian peasants from taking pot-shots at German paratroopers in 1940 as though out hunting game on the flats; later, as a member of the Royal Army Medical Corps in the Pacific, he recalled the horror of re-entering hospitals with patients disembowelled in their beds by the Japanese when they overran allied positions. I remember a father who fell curiously silent, with memories he could not share; a mother who had broken down and fled the Blitz to join the land army in the countryside.

As children, our thoughts, while vastly expanding in extent and depth, are rapidly taken up and developed within family and society, as we are not just educated in facts, but also indoctrinated into every kind of myth. The idea that we can objectively learn lessons from history must therefore be taken with a pinch of salt, though we should never be deterred from trying.

The story of the origins of the Second World War has long been used by politicians as a dramatic allegory for the international crises of the present. The stark lesson drummed into the immediate postwar generationcertainly in Britain, where the consequences of navet were the most severe, but also in France, which suffered so much from the failure of Britain to lead in the right direction, and in the United States, which at first stood aside but eventually had to carry the burdenwas that appeasing dictators only whets their appetite.

Subsequently the lesson was successfully applied in the Cold War against the Soviet Union, where the command economy ultimately collapsed, squeezed by competition with the United States. Butand this too should not be forgottenit was equally disastrously misapplied, most notably against Nasser of Egypt by Sir Anthony Eden in 1956. No doubt both the use and the abuse of history will continue.

There is, however, another crucial lesson from the story that has all too frequently been overlooked. Our understanding of international relations in the twentieth century cannot be reduced to the simplicity of traditional balance-of-power politics without doing serious damage to the truth. The indifferent application of our understanding of inter-state relations in one epoch to an entirely different time is not a sound recipe for success, as historian A.J.P. Taylor discovered when he moved from analysing the nineteenth century to explaining a very different twentieth century.