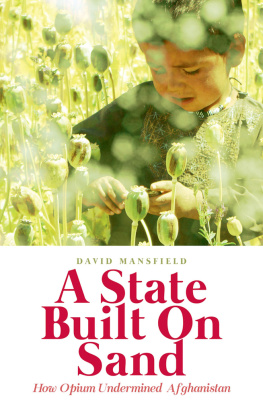

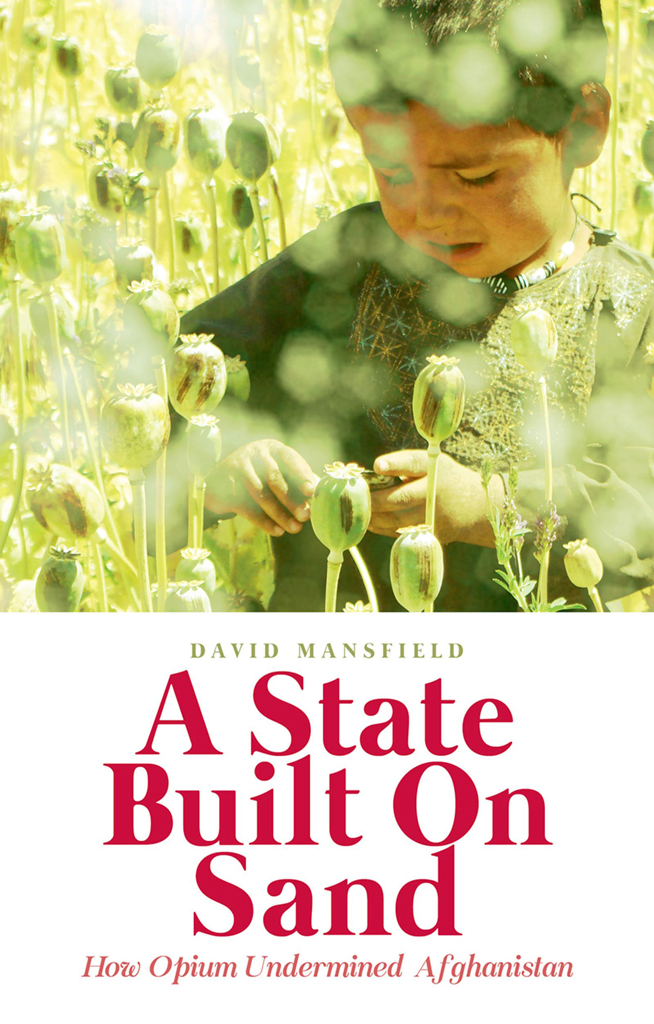

A STATE BUILT ON SAND

DAVID MANSFIELD

A State Built on Sand

How Opium Undermined Afghanistan

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

OxfordNew York

AucklandCape TownDar es SalaamHong KongKarachi

Kuala LumpurMadridMelbourneMexico CityNairobi

New DelhiShanghaiTaipeiToronto

With offices in

ArgentinaAustriaBrazilChileCzech RepublicFranceGreece

GuatemalaHungaryItalyJapanPolandPortugalSingapore

South KoreaSwitzerlandThailandTurkeyUkraineVietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Copyright David Mansfield 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available David Mansfield

A State Built on Sand: How Opium Undermined Afghanistan.

ISBN: 9780190608316

eISBN: 9780190694715

To

Joanne, Ben and Nathan

CONTENTS

This book would not have been possible without the support of a lot of different people. Most notable is the European Commission and their generous support to the Afghan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU). Giacomo Miserocchi at the European Commission (EC) stands out in particular as someone who fundamentally believed that documenting almost two decades of fieldwork in Afghanistan and experience in the drugs policy world was a useful exercise that needed support. AREU and its staff have helped in the completion of this task and provided long-term support to my fieldwork in rural Afghanistan.

There are others who have supported my research over an extended number of years: individuals in a range of institutions who stand out for their commitment to developing a more detailed understanding of how policies and programmes were working on the ground in Afghanistan. Many did this despite knowing that senior managers or other agencies were not always keen to know or be presented with evidence of impact. These individuals shall remain anonymous here but I am forever thankful for the funding they have provided and the support they gave to simply documenting the lives and livelihoods of rural Afghans without any desire to influence the findings of the research.

In terms of the substantive part of the work in Afghanistan, particular thanks go to my colleagues and now close friends at the Organisation for Sustainable Development and Research (OSDR) who have spent a considerable amount of time with me in rural Afghanistan, enduring my predilection for asking far too many questions. The support given by Hajji Sultan Mohammed Ahmady, Ghulam Rasool, Hajji Hasti Gul and Azizullah for well over a decade is immeasurable. They have been patient throughout and have kept me out of trouble on many occasions. I am truly thankful for their com mitment and friendship over such an extended period of time. There are a number of other colleagues at OSDR, individuals who live and work in some of the most insecure parts of the country and who have shown such generosity in sharing their time and knowledge. None of this work would have been possible without them.

There are also Richard Brittan and the team at Alcis Ltd, particularly Matt Angell, Dilip Wagh and Tim Buckley. The work they do with geospatial imagery and analysis is truly pioneering, and when combined with well focused fieldwork and a detailed understanding of the ground, it can provide an unrivalled understanding of the nature of change in the lives and livelihoods of the population in some of the most conflict-affected parts of Afghanistan.

There is a group of colleagues who have offered considerable advice and input on the numerous papers that I have written over the past eighteen consecutive growing seasons. Special thanks go to Michael Alexander, Rory Brown, William Byrd, Pierre Arnaud Chouvy, Matt Dupee, Pierre Fallavier, Paul Fishstein, Anthony Fitzherbert, Tom Franey, Arunn Jegan, David Macdonald, Dipali Mukhopadhyay, Ronald Neumann, Ian Patterson, Ghulam Rasool and Richard Will. These individuals have put a considerable amount of time into providing comments, and their insights are much appreciated. The work is so much better for their contributions.

My good friend and academic supervisor Jonathan Goodhand also merits particular thanks with regard to the substantive part of my work and its evolution over the last decade. Jonathan has always been patient and supportive, as well as tolerant of my failure to meet deadlines. He has constantly pressed me to look beyond the findings of my last piece of fieldwork and pointed me in the direction of wider literature and ideas that have proved to be invaluable for developing a better understanding of the complex reasons why opium bans endure in one area and collapse in others. I have learned a lot from our work together.

Of course there are also the countless farmers and rural communities that have welcomed me and my colleagues over the last eighteen years of fieldwork. They have shared their time, their experiences and the details of their lives and livelihoods, and have shown incredible hospitality despite many having so little to spare. Some have warned us of security problems, even imminent dangers, and for that I will be eternally grateful.

There are others who have been instrumental to the body of work that makes up this book, providing support at critical junctures: Michael Alexander, David Macdonald and Richard Will, partners in crime during those formative years at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, UNODC; Michael Ryder, Peter Holland, Guy Warrington, Andy Smith, Dave Belgrove, Ian Patterson, Robert Magowan and Tom Franey for their unwavering commitment to doing the best job possible; I learned a lot from them during my time at the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and they made the experience so much more pleasant than it could have been and it subsequently became; Christoph Berg at GTZ, a person who was ahead of his time and willing to press for a different approach to rural development in drug crop-producing and abandon the concept of alternative development despite the fact that to do so would not serve his interests; Paul Fishstein and Andrew Wilder for establishing the foundations for the empirical work at the Afghan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), and along with Nigel Pont their support while in Boston; Robert Vierkant and Said Maqsoudi of the US Department of Defence for much needed support in writing up work on the Taliban ban and some of my old field notes; Jean Luc Lemahieu at UNODC for the dinners and all the entertaining and informative debates we have had on the drugs issue in Afghanistan over the course of many years; finally, Rory Stewart and the Kennedy School for their invitation to undertake a fellowship at Harvard, which led to new opportunities in Boston for me and my family, for which we will always be thankful.