To the memory of my father,

and his indefatigable curiosity.

And his delight in reading the closest thing to hand,

whether that was his trigonometry, cereal boxes,

the telephone book or the old newspapers when he should

have been lighting the fire. But never this book.

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

INTRODUCTION

The only thing that is good

In mankinds search for temporary oblivion, opiates possess a special allure. For a short time, there is neither pain, nor fear of pain. Since Neolithic times, opium has made life seem if not perfect, then tolerable, for millions. However unlikely it seems at this moment, many of us will end our lives dependent upon it.

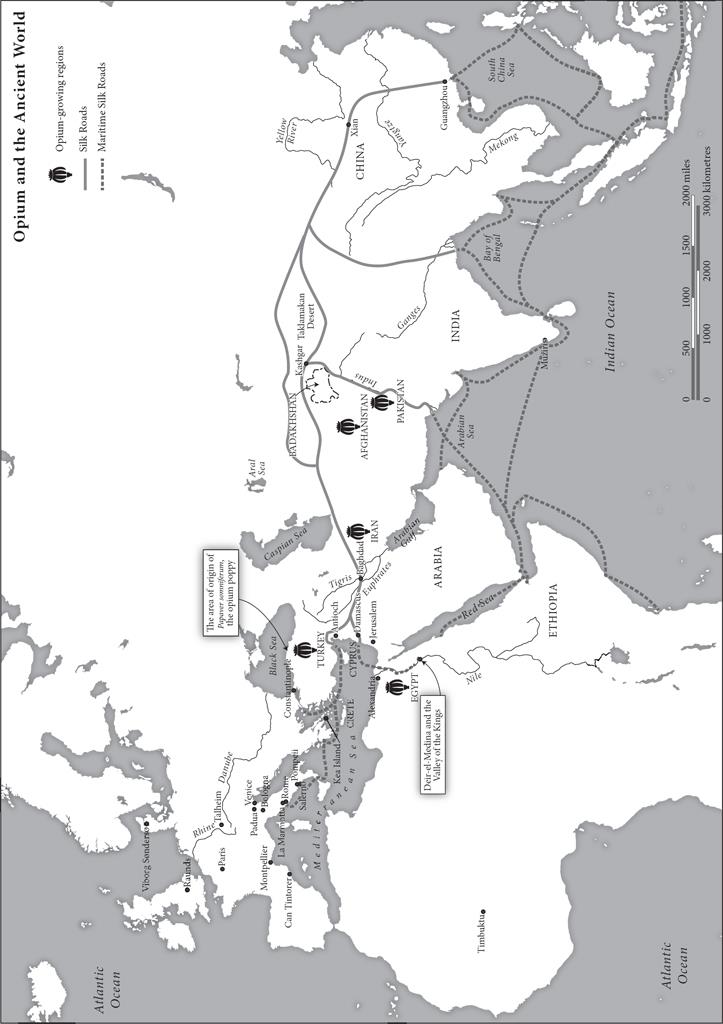

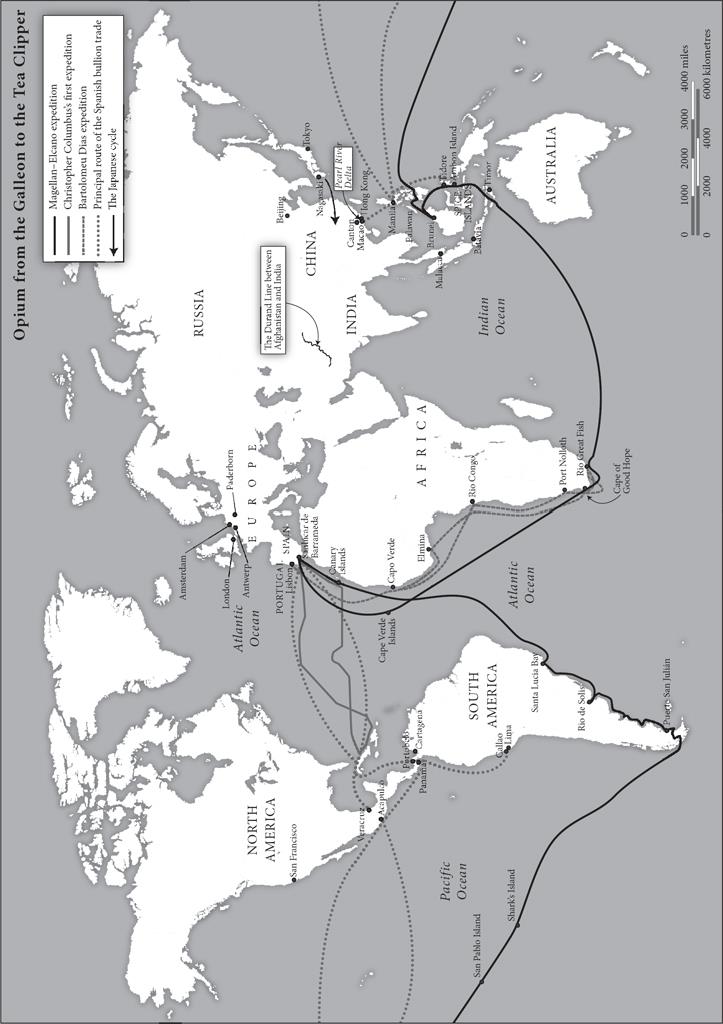

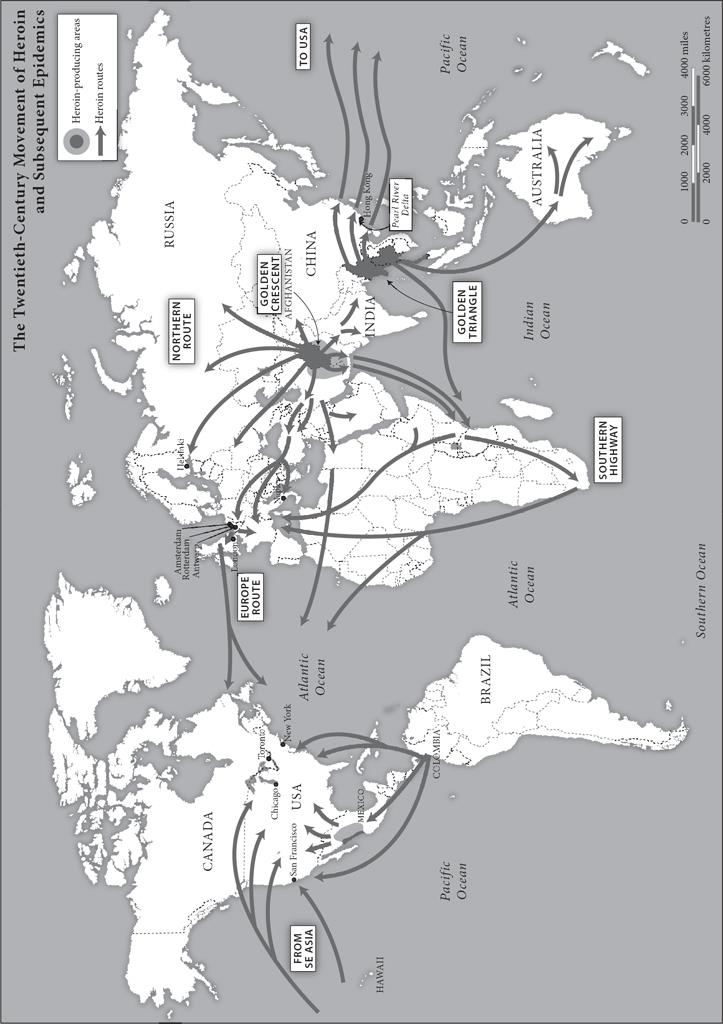

Indefensible but as yet indispensable, the opium poppy, and now its chemical mimics, endure and multiply. They cross continents, religions, cultures, languages and time. Milk of Paradise attempts to address this long history and the current, often galling compromises to be made as the world moves towards a model that is based increasingly upon the control of natural resources and expanding alternative economies. It is a journey from the ancient world to present-day America, along routes of legal and illegal commerce that belt the globe.

This book charts the evolution of one drug, although others feature in cameo roles. It seeks to provide a non-partisan view of this remarkable substance, and to dispel at least some of the myths surrounding opiates and the uses we put them to, and why. It began, in part, in Londons Farringdon Station, in 2002, when I was forced by necessity to avail myself of the desperately squalid public convenience there at the time. As a child of the Reagans Just Say No campaign, the filthy, fluorescent-lit and heavily graffitied single cubicle was the stuff of bad dreams, only to be used in a dire emergency. By the sink, staring into the mirror, was a grubby young woman in baggy clothing who, startled by my urgent entrance, dropped what she was holding into the sink with a clatter. The obligatory tiny wrapped parcel, the spoon and syringe were there, and also a rubber band. Im sorry, she said immediately, flustered, and began to gather up her precious stuff. Pushing past me, out into what was not the gleaming commuter hub visible today, but at the time a grim focus for central Londons flotsam of homeless and addicts, she apologized again. It wasnt me she was apologizing to.

Since that encounter, I have witnessed and experienced diamorphine used in medical surroundings, where everything is clean and warm, and I trusted those administering the drug. As a carer for dying family members, I have juggled my charges morphine doses, wondering whether five milligrams more will mean we can just make it home, or through the night without incident, and drunk liquid morphine to prove that Come on, its really not that bitter. It really is that bitter. I have also watched as diamorphine induced respiratory failure in those people, over a period of hours and days, as their lives came to an end as peacefully as possible. And I have been impossibly grateful for a drug that allowed them to continue to live well, even as they were in the process of dying.

The research this book has entailed, although set in motion by personal experience and a cursed curiosity, has been both desk- and field-based. The former attempts, in the main, to reduce opiates, and now opioids, to a numbers game: kilograms seized, hectares burned, numbers arrested. The latter contains the human stories of addiction and recovery, of war, and treatment from both ends of the doctorpatient spectrum, but above all, the existential needs that drive humanity to seek the temporary relief opiates provide. It has been a transformative experience: exposing me to the reality of a global economy I had only a vague notion of before, and a redrawing of the world map not only in terms of borders, but a lack of them. Organized crime, in its purest form, is simply another economy, borderless and amoral. The importance of personal relationships and credit lines are not only mechanisms in the legal economy, they are equally if not much more powerful in illegal economies. These networks operate increasingly on efficient corporate models of collaboration and middle management. Notions of what is transgressive, illicit and ultimately illegal have changed dramatically over time, and continue to change as the worlds governments and drug-enforcement agencies fight turf battles in an international war.

Milk of Paradise is divided into three parts: the stories of opium, morphine and heroin. Part One is a history of the opium poppy, its earliest relationships with mankind, and its transformation into one of the first commodities traded between the West and the East. Part Two concerns the isolation of morphine from opium, and the revolutionary scientific and political changes, as well as chemical discoveries that transformed the West in the nineteenth century, and set us on a course that, as it accelerated, changed the face of the world, from Tombstone, Arizona to the Durand Line dividing Afghanistan and Pakistan. The third and final part covers the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, from the first years of commercially available heroin, the associated growth of Big Pharma and the present-day US opioid crisis, and charts the successive global wars on and involving drugs, as well as treatment, prohibition and attempts at the suppression of the trade in heroin and its derivatives. Because of the major roles they have played in the establishment and continuation of the opiate trade, the book focusses mainly on Britain, Europe and America.

Ultimately, Milk of Paradise is a tale of the many interwoven human stories that make up the history of our relationship with this fascinating compound. Taken together, they show us how opium has developed and how it will go forward. Historically, it is central to the advances in modern medicine, and the Eastern Triangular Trade, along with tea and bullion. The Opium Wars in the middle of the nineteenth century helped lay the foundations of Hong Kong, and of modern China. The drug has played a key role in conflicts from the American Civil War, to Vietnam and to Afghanistan, where Camp Bastion was a pioneering field hospital in the middle of the worlds largest illicit poppy plantations. Scientifically, opium and its many derivatives lie at the heart of the surgical and pharmaceutical industries. Socially, the drug is both a tremendous force for good and an indescribable evil. It gives comfort to millions daily as part of a lucrative healthcare system, yet it creates addictions that fuel the worst kinds of degradation and exploitation, and plays a major role in all layers of worldwide crime. Our relationship with opium is a deep-seated part of our human history, and a critical part of our future.

Therefore, perhaps it is fitting that I write this introduction in Fort Cochin, an old colonial outpost on the Malabar Coast of southern India, which was once a great trading port with ties as far away as Mexico. An even greater one, Muziris, dominated by Jewish, Arab and Chinese traders and lost since 1346, has just been rediscovered by archaeologists some twenty miles up the coast. Once one of the worlds greatest hubs for exotic goods and spices, the only map of Muziris if it can be called a map at all is a copy of one that may be as early as the fourth century AD , which resides in a museum in Vienna and which is itself a copy of a first-century BC map by Agrippa.