Contents

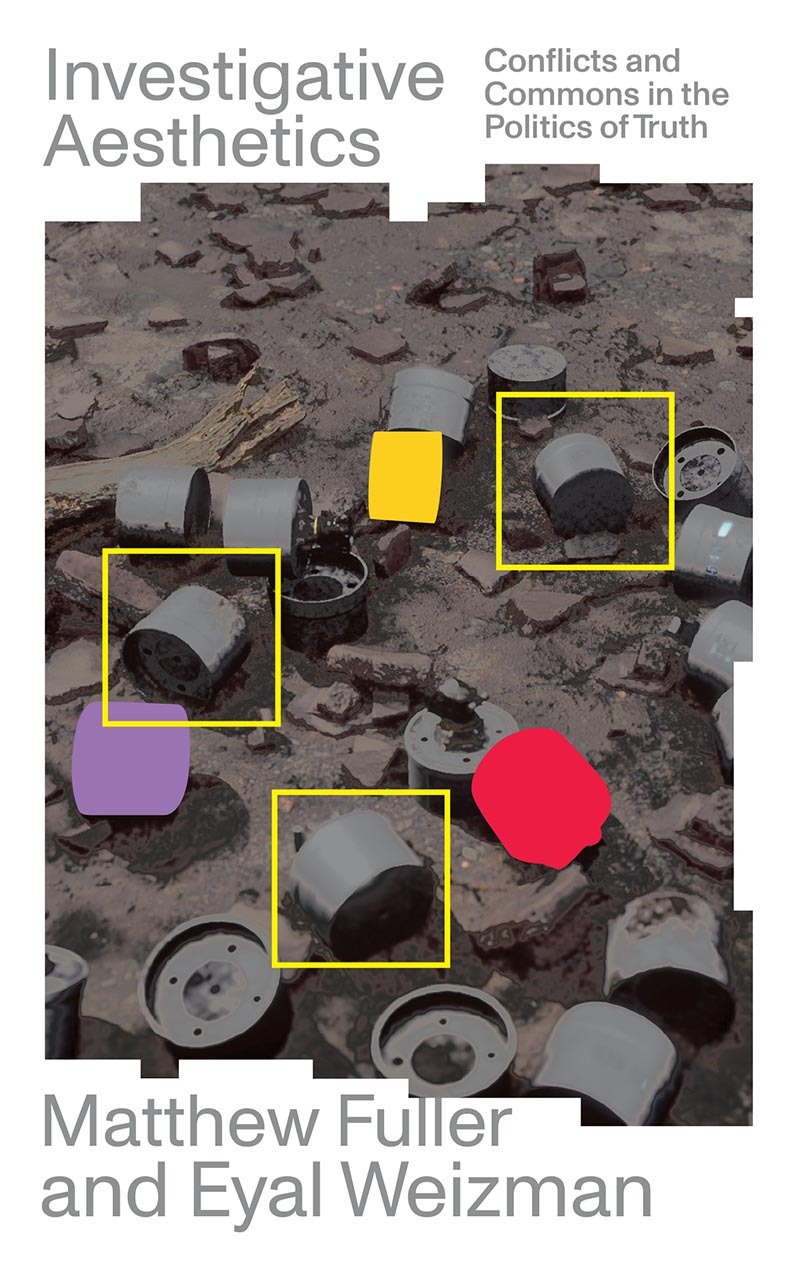

Investigative Aesthetics

Investigative Aesthetics

Conflicts and Commons

in the Politics of Truth

Matthew Fuller

and

Eyal Weizman

First published by Verso 2021

Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman 2021

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-908-5

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-910-8 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-909-2 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021930159

Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

Violence lands. Hundreds of troops break into a city. At that moment the city starts recording its pain. Bodies are torn and punctured. Inhabitants memorise the assault in stutters and fragments refracted by trauma. Before the Internet is switched off, thousands of phone cameras light up. People risk their lives to record the hell surrounding them. As they frantically call and text each other, their communication erupts into hundreds of star-shaped networks. Others throw signals into the void of social media and encrypted messaging, hoping they will be picked up by someone. Meanwhile, the environment captures traces. Unpaved ground registers the tracks of long columns of armoured vehicles. Leaves on vegetation receive the soot of their exhaust while the soil absorbs and retains the identifying chemicals released by banned ammunition. The broken concrete of shattered homes records the hammering collision of projectiles. Pillars of smoke and debris are sucked up into the atmosphere, rising until they mix with the clouds, anchoring this strange weather at the places the bombs hit.

Each person, substance, plant, structure, technology and code in this incident records in a different way. Some traces accumulate so fast and haphazardly that they erase previous traces. These records, traces of destruction and pain, are both modes of aesthetic registration and modes of erasure. When they remain, such traces may, given the right techniques, be read for different purposes: some for furthering violence, others for opposing it or simply to stay alive somehow. Those that are obfuscated or repressed are more difficult to access. Those delivering violence have recourse to higher-resolution sensors: cameras on drones, planes and satellites to record clashes from multiple perspectives. Their overwhelming power relies on weapons, but also on access to information gathered as floods of images and signals and the means of working through these streams of data, using AI for interpretation and prediction. While massive collection takes place, such violence also consists of a simultaneous attempt to impose on those experiencing the attack a uniform and impenetrable block of information, one that reads as information from one side and as noise on the other.

That difference between signal and noise will also be used to allow officials of all kinds to lie about what happened, spread disinformation, marshal or manipulate data, and deny the most basic of facts. Later, those experiencing or resisting the violence will testify. Perhaps a soldier will have the guts to reveal what they or their comrades have done either publicly or by leaking secretly downloaded files. Another might do so accidentally, while bragging on their social network.

However, there can also be a counter-reading, a counter-narrative that gathers all these different kinds of trace, and is attuned to their erasure. Reworking what sometimes are merely weak signals forming a composite from all of these recordings can show what happened and what political conditions gave rise to it. Interpreting weak signals and faint traces is complicated as only an act of close reading can be. Weaving these signals in relation to each other is not only a scientific or technical endeavour but a cultural, ethical and political one. It involves wide and varied ways of paying close attention to the accounts of people, matter and code. To those experiencing violence first-hand who lead the struggle for something approximating justice, the question is always how finding the truth about current events may also reveal the shadow of long-term historical processes, and how telling history from the lived perspective of present violence can support their political struggles. To be effective, contesting official accounts of what has happened is a question of investigation, of history and of solidarity, and such telling is only as good as the political process of which it is part.

_____

A bomb is released from a Saudi warplane and blows up in a hospital in Yemen. The bomb is a composite object, its many components arrived from dozens of factories across Europe and the US. These products are themselves assembled from other products drawn from hundreds of subcontractors, and these are supplied by providers of raw materials, which are in turn extracted from mines spread across the world. The bombs assembled structure is coextensive with the global economy. When it hits a target it sprays its fragments in all directions, tearing bodies and properties and destroying life-worlds. These shards of the bomb do not directly correspond to the assembled components or products but raggedly approximate them in a transformed state.

Survivors of such strikes often make a point of photographing these fragments and uploading the photos online. Other people look, trying to compare and identify those fragments and trace them to the companies that made them. Legal activists use this material to force a moratorium on further export. The process of investigation resembles watching this act of bombing in slow-motion rewind, like the scene in Kurt Vonneguts novel Slaughterhouse-Five where the devastating bombing of Dresden is told in reverse. From the rubble and fragments a bomb is reassembled; it is then shot upwards into one of the wings of a plane, which flies backwards and lands it in an airfield, allowing the bomb to be dismounted and then disassembled, shipped elsewhere, where it is separated into components, each sent further back into the part of the world that gave birth to it; the raw metals are then placed back in deep mines and covered with earth, which is replanted with forests, so that they cant hurt anyone ever again.

In this book, we argue that an anti-hegemonic investigation, drawing out and combining individual recordings until they become collective a commons is an intrinsically aesthetic practice. By understanding this capacity for collective sensing and sense-making, we can work towards a renewed, careful, but politically powerful conception of truth practices today. In the pages that follow we want to suggest some considerations on the political stakes of such a formation. This book, which we each came to from different directions, is not a historical overview of the intersection of aesthetics and investigations; it is rather our attempt to think theoretically about our own and some of our colleagues practices, the terms, components and assumptions that form the source code of what we do, and to reflect upon the contours of our ambitions regarding what we have not achieved but that remains to be done.