Names: Bates, David, [date] author.

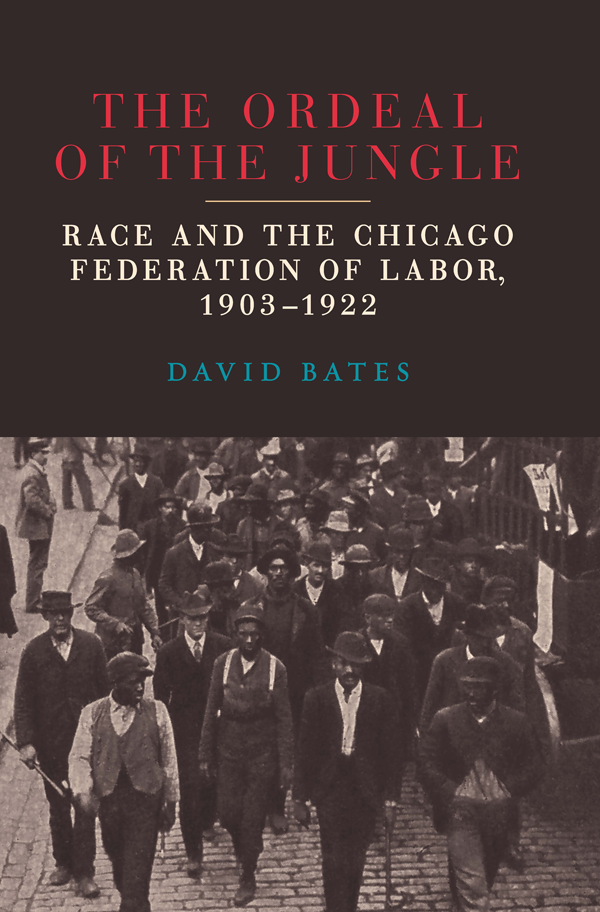

Title: The ordeal of the jungle race and the Chicago Federation of Labor, 19031922 / David Bates.

Description: Carbondale, IL : Southern Illinois University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018050718 | ISBN 9780809337446 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780809337453 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Chicago Federation of Labor and Industrial Union Council--History--20th century. | African Americans--Employment--Illinois--Chicago--History--20th century. | Chicago--Race relations--20th century. | Chicago Race Riot, Chicago, Ill., 1919. | Working class--Illinois--Chicago--Social conditions--20th century. | Labor movement--Illinois--Chicago--History--20th century.

Classification: LCC HD6519.C442 B38 2019 | DDC 331.8809773/1109041--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018050718

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Some clichs are clichs because theyve been proven true; perhaps none more than the truism that writing a book is a social act. With that in mind, I must first offer thanks to James Barrett, Clarence Lang, Sundiata Cha-Jua, and David Roediger for their perceptive critiques of early versions of this manuscript. I also received tremendous support from colleagues (and friends) Ashley Howard, Alonzo Ward, Kerry Pimblott, and Stephanie Seawell. Each proofread multiple drafts of this book, and each provided a unique critical perspective on everything from theoretical orientation to structure and organization to word choice. Guidance through the publishing process was provided by James Wolfinger and Roxanne Owens of DePaul University and David Settje of Concordia University Chicago.

This book would not have been possible without generous financial assistance provided by a publication grant from the Textbook and Academic Authors Association, and by the College of Arts and Sciences at Concordia University Chicago. Special thanks are due to O. John Zillman and Rachel Eells at Concordia for their assistance in this process.

The images that appear on this books cover, and in four of its six chapters, were surprisingly difficult to locate and obtain, and I could not have done so without the patient assistance of Leslie Martin and Angela Hoover of the Chicago History Museum and Val Harris of the Special Collections department of Daley Library at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Jason Davis of Chicago Scanning also deserves thanks for his expert assistance in digitizing selected images.

I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to the staff of Southern Illinois University Press. During my eighteen months preparing the initial manuscripta daunting prospect for a first-time authorSylvia Frank Rodrigue patiently fielded my questions, assuaged my anxieties, and guided me through the process of being a first-time author. It is not an overstatement to say that without her hard work, her generosity, and herencouragement, this book would not exist. As I completed final editing of the manuscript, the patience and expertise of copyeditor Lisa Marty, indexer Sherry Smith, and, in particular, project editor Wayne Larsen all proved invaluable as well.

My deepest thanks go to my partner, Meg. Her eyes were the first to proofread every draft, and her questions, comments, and critiques were vital. More importantly, she imparted an invaluable sense of calm, even when I was at my most exhausted and frustrated. Her loving support was my greatest inspiration in finishing this long, difficult, and ultimately rewarding process.

INTRODUCTION: RACE AND AMERICAN LABOR HISTORY

In the summer of 1919, Chicago exploded into a weeklong paroxysm of racial violence that left thirty-eight people dead, more than five hundred injured, and more than a thousand homeless.

But the Chicago race riot was also the climax of another, longer story: the efforts of the citys labor leaders to organize an interracial union. By the time of the riot, the Chicago Federation of Labor (CFL) had been working for more than two years to organize the citys stockyards without regard to race, ethnicity, gender, or skill level. Initially at least, these efforts were enormously successful. At various points, it was estimated that in many departments, white and black participation in the Stock Yards Labor Council (SLC), as the organizing body was called, exceeded 90 percent. But by the time of the riot, the SLCs position in the black community had become tenuous at best; the violence of the riot and the recriminations of its aftermath would make their presence positively toxic. Within months, the SLC would be disbanded entirely. By early 1922, after abortive last-ditch strikes in steel and meatpacking, the CFL would recede into obscurity for more than a decade. Reflecting on these failures, a black trucker later explained that he had got along fine during a stint as a union butcher. But that stint had been brief, and left him suspicious toward unionism. Strikes are too hard on the man that aint in the union, The anonymous workers wariness was born of hard experience. By the early 1920s, African Americans felt forcibly estranged from Chicagos labor movement.

This book traces the long and complex history of that estrangement, and of the complex interplay of forcesorganizational missteps, shop-floor confrontations, and employer predationthat produced it. Labor unions had built a long and infamous history of racial exclusion by the time of the CFL campaign. Most unions were craft oriented and thus shunned unskilled workers, immigrants, and African Americans. Though the CFLs leaders earnestly sought to transcend such bigotry, their view of racial inclusion was limited and the structure of their campaign produced a de facto segregated union that proved repellent to black workers. White union members took this intransigence as substantiation of longstanding suspicions that African Americans were a scab race. Employers targeted the union mercilessly, using strategic hiring and firing practices to enflame racial tensions, divide their workforce, and defeat the campaign. As a result, both black and white workers entered the 1920s as easy prey for the whims of bosses.

Previous historians have examined this phenomenon in a variety of ways. Practitioners of the so-called old labor history, distinguished by its focus on the structure of union institutions and campaigns, analyzed the chasm between the stated commitment of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) to colorblind organizing and the frequently (and often openly) racist nature of its unions. These historians largely concluded that racial conflicts within the working class were produced by racist union structures and the divide-and-conquer tactics of employers. Philip Foner raged against the AFLs accommodation of whitewashed trade unions, while Sterling Spero and Abram Harris argued that unions largely viewed African Americans as member[s] of a race which must not be permitted to rise to the white mans level.

The so-called new labor history inverted this approach; rather than examining large-scale structures of union organization, new labor historians focused their energies on local studies of workers attitudes and culture. As a result, many scholars have focused their attention more on moments of contact and even cooperation between white and black workers.