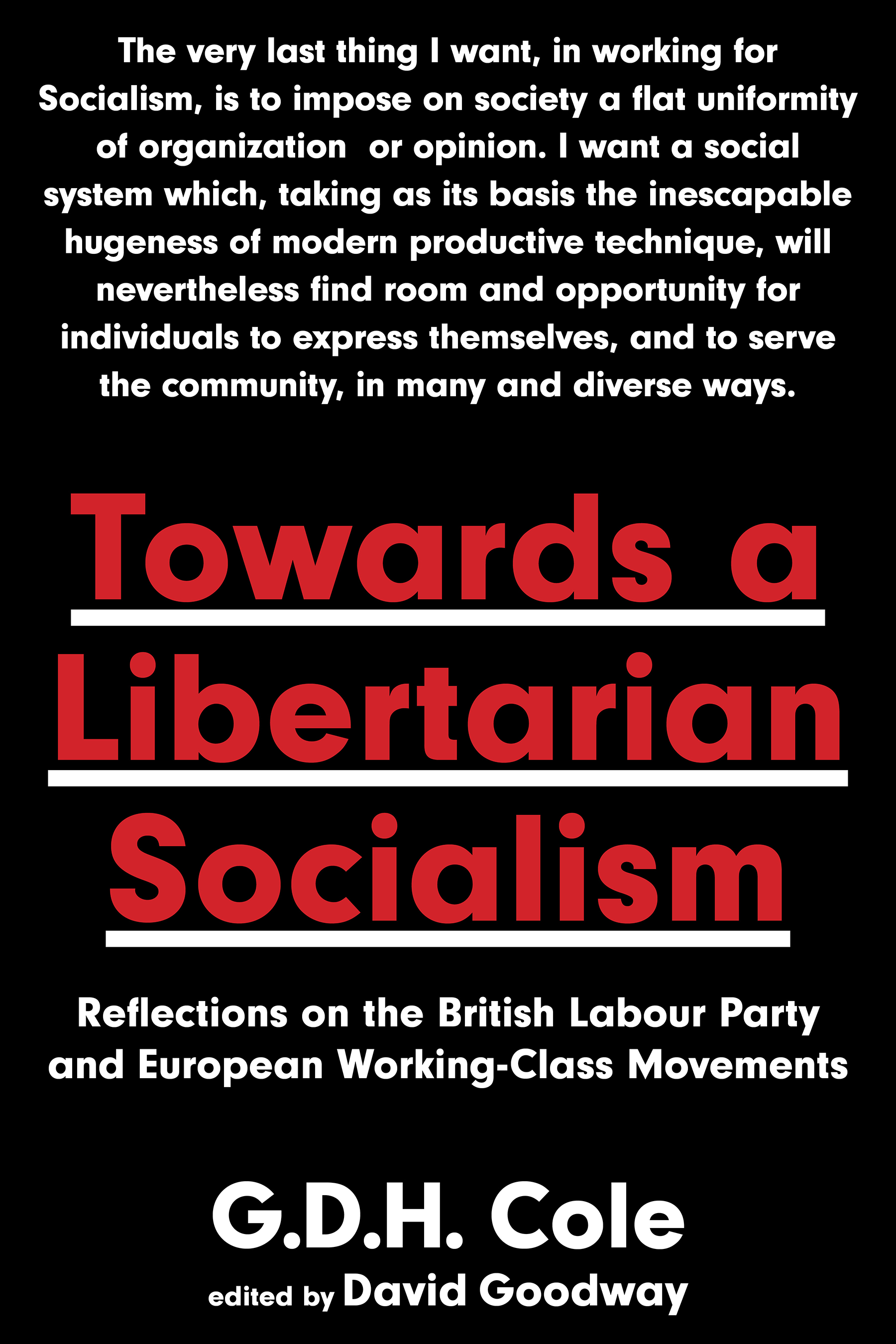

G .D.H. COLE

G.D.H. Cole: A Libertarian Trapped in the Labour Party

From the 1920s until his death in 1959, G.D.H. Cole was the pre-eminent Labour intellectual, surpassing Harold Laski and R.H. Tawney in the proliferation of his publications and general omnipresence. His History of the Labour Party from 1914 (1948) was, for many years, the standa rd text.

Yet Colin Ward was to comment in Anarchy that h e had been

amazed as I read the tributes in the newspapers from people like Hugh Gaitskell and Harold Wilson alleging that their socialism had been learned from him...for it had always seemed to me that his socialism was of an entirely different character from that of the politicians of the Labour Party. Among his obituarists, it was left to a dissident Jugoslav communist, Vladimir Dedijer, to point what the difference was; remarking on his discovery that Cole rejected the idea of the continued supremacy of the State and believed that it was destined to disappear.

Ward appreciated that Cole was a socialist pluralist. Indeed his major intellectual and organizational effort had been to Guild Socialism.

***

The origins of Guild Socialism are customarily traced to 1906 and the publication by Arthur J. Penty of The Restoration of the Gild System . Pentys advocacy of a return to a handicraft economy and the control of production by trade guilds looks back, beyond William Morris, toas he cheerfully indicatesJohn Ruskin. He had been a member of the West Yorkshire avant-garde responsible for the foundation of Leeds Arts Club, in which the dominant personality was A.R. Orage, who himself moved to London, taking over (with Holbrook Jackson, another Leeds man) the weekly New Age in 1907. Orage had a very considerable input in the emergence of Guild Socialism in the New Age s columns. He published a series of articles in 191213 by S.G. Hobson, an Ulsterman then managing a banana plantation in British Honduras, and when Orage collected these as National Guilds he located the kernel of Hobsons ideas in Pentys work and also an article of his own (Orage had certainly collaborated with Penty in the development of The Restoration of the Gild System ), yet these attributions were to be forcefully denied by Hobson, himself.

In contrast to Penty, Hobson envisaged the trade unions converting themselves into enormous National Guilds which would take over the running of modern productive industry as well as distribution and exchange. An anonymous article in the Syndicalist , written presumably by the editor Guy Bowman, c omplained:

Middle-class of the middle-class, with all the shortcomings...of the middle-classes writ large across it, Guild Socialism stands forth as the latest lucubration of the middle-class mind. It is a cool steal of the leading ideas of Syndicalism and a deliberate perversion of them.We do not so much object to the term guild as applied to the various autonomous industries, linked together for the service of the common weal, such as advocated by Syndicalism. But we do protest against the state idea which is associated with it in Guild Socialism.

As Hobson/Orage explained, alongside and independent of the Guild Congress the State would remain with its Government, its Parliament, and its civil and military machinery....Certainly independent; probably even supreme..)

***

George Douglas Howard Cole was born in 1889 in Cambridge, the son of George Cole, a pawnbroker, and his wife Jessie (ne Knowles), whose father kept a high-class bootshop in Bond Street. The Coles soon moved to Ealing, west London, where George Cole was able to acquire a flourishing estate agents. Douglas (as he was always known) was educated at St Pauls School, Hammersmith; and it was, he recalled in 1951, while a schoolboy that he became a socialist:

I was converted, quite simply, by reading William Morriss News from Nowhere , which made me feel, suddenly and irrecoverably, that there was nothing except a Socialist that it was possible for me to be. I did not at once join any Socialist body. I was only sixteen....My Socialism, at that stage, had very little to do with parliamentary politics, my instinctive aversion from which has never left meand never will. Converted by reading Morriss utopia, I became a Utopian Socialist, and I suppose that is what I have been all my life since. I became a Socialist...on grounds of morals and decency and aesthetic sensibility. I wanted to do the decent thing by my fellow-men: I could not see why every human being should not have as good a chance in life as I; and I hated the ugliness of both of poverty and of the money-grubbing way of life that I saw around me as its complement. I still think these are three excellent reasons for being a Socialist: indeed, I know no others as good. They have nothing to do with any particular economic theory, or theory of history: they are not based on any worship of efficiency, or of the superior virtue or the historic mission of the working class. They have nothing to do with Marxism, or Fabianism, or even Labourismalthough all these have no doubt a good deal to do with them. They are simple affirmations about the root principles of comely and decent human relations, leading irresistibly to a Socialist conclusion.

He joined the Ealing branch of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) shortly before leaving school and then, a few months later, I celebrated my first week in Oxford by joining the University Fabian Society and its parent body in L ondon...

From 1908 he read Mods and Greats (Classics) at Balliol, graduating in 1912. He accepted a lectureship in philosophy at Armstrong College, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, which oddly he loathed, but was almost immediately rescued by being elected to a seven-year Prize Fellowship at Magdalen College, Oxford. His first book, The World of Labour: A Discussion of the Present and Future of Trade Unionism , an admired and influential study of developments in the USA, France, Germany, Sweden, and Italy as well as Britain, was published as early as 1913. What impressed him was the way in which contemporary syndicalist tendencies believed it possible to progress to workers control of industry without reference to parliamentary institutions. In The World of Labour he is also found discovering Guild Socialism from the pages of the New Age . Raymond Postgate, his future brother-in-law, recoll ected that

A schoolboy friend lent me The World of Labour , taking it away when I had read it through, and forcing me to buy my own copywhich I was glad enough to do, for it had in fact opened a completely new world to me. The education which I, and every other middle-class boy, had received, had not referred to one single thing mentioned in the book.

Coles intellectual and political commitment to the trade-union movement deepened in 1915 when he was appointed as an unpaid research officer to the Amalgamated Society of Engineers (ASE), the first university graduate to be engaged by a British union. His conscientious objection to conscription was allowed as long as he undertook this work of national importance. He developed a highly original theory of functional democracy, rejecting democratic representative government in favour of a pluralistic society in which representation would be functionalthat is, derived from all the functional groups of which the individual is a member (the most important are named as political, vocational, appetitive, religious, provident, philanthropic, sociable and theoretic), final decisions having to emerge as a consensus between the different groups, not as the fiats of a sovereign authority: