Also available from Bloomsbury:

Food, Masculinities and Home, edited by Michelle Szabo and Shelley L. Koch

Making Aboriginal Men and Music in Central Australia, Ase Ottosson

The Performance of Gender, Cecilia Busby

BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2019

Copyright Geir Henning Presterudstuen, 2019

Geir Henning Presterudstuen has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

For legal purposes the constitute an extension of this copyright page.

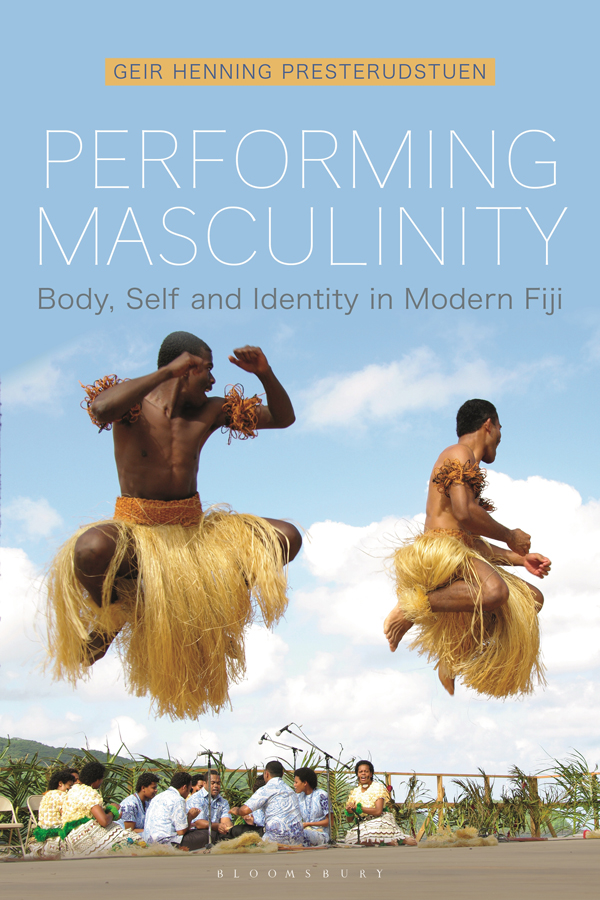

Cover image Vincent Talbot / Getty Images

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: HB: 978-1-3500-4334-3

ePDF: 978-1-3500-4335-0

eBook: 978-1-3500-4337-4

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters.

Contents

Some thirty years after the masculinity turn in social science research, the concept seems more central to contemporary discussions than ever before. As part of a zeitgeist in which identity politics has come under renewed scrutiny and the divisions in a number of social justice discourses have seemingly sharpened, the notion of masculinity as a social category has captured the public imagination and has made its way beyond academic institutions. On one level, the notion of toxic masculinity is frequently given explanatory power in discussions about gendered violence and sexual assault as well as in other forms of problem behaviours in which men are over-represented as perpetrators. On another level, a bourgeoning field of mens rights activists and commentators are proffering the notion that men and their masculinities are under sustained and unfair attack from feminists, critical theorists and liberal politicians. In both these analytical narratives, men, of the traditional Euro-American working classes, those whom the sociologist Michael Kimmel labelled angry white men in his 2013 publication, have come to represent the frustration and discontent permeating late modern life. Increasingly, it is the discontent of these groups that is seen to fuel local and global conflicts and is harnessed by political forces that see the protection of mens privilege as central to a broader agenda of defending Western traditions and values against an ill-defined group of others that includes women, non-Westerners and marginal men of all categories.

Despite the Western-centric nature of these discourses, many of the same issues are mirrored in the global south where they emerge in tandem with a series of long-standing structural dynamics that define global inequalities. Still, perspectives from these locales are much less prevalent in popular as well as academic discussions. This book is, among other things, an attempt at showing what anthropological insights about how men construct and perform masculine self-identities in a rapidly changing context outside the Euro-American centre can add to our understanding of gender, modernity and some of the key challenges of our present time.

This conceptualization follows the analytical move proposed by bell hooks, the prominent American feminist, in her influential book Feminist Theory: From Margin to Centre in 1984. Using her own experience of coming of age in an underprivileged black community in a racially divided southern town in 1960s United States, hooks formulates a strong argument for the need to privilege the views of the marginalized in order to better understand complex social dynamics. Being marginalized, black Americans had a dual perspective on their town and their own circumstances that privileged white people, insulated from their black counterparts by social class and railroad tracks, did not have: We looked both from the outside in and from the inside out (hooks 1984: ix). This principle, of building critical theory based on insights from the margin, became the linchpin for hookss new feminist theory, and has since been taken up by a number of scholars seeing the scientific value of building knowledge from the outside in. Of particular interest to my project is the work of R. W. Connell who has continued her groundbreaking scholarship in theorizing masculinities with a sustained focus on Southern Theory (2007) and world-centred thinking (2014). These ideas serve as an inspiration for my research in that they emphasize how marginal perspectives deserve to be heard and analysed not just based on a commitment to social justice but also because they provide valuable knowledge we otherwise would not gain access to.

In Fiji, constructing and performing masculinity has long been considered a way to ensure mobility from the margin to the centre. Local indigenous elites navigated the demands of early colonists to remain in charge of colonial Fiji through a system of indirect rule, ensuring the continuous authority of local patriarchs. Other natives demonstrated physical prowess and strength to gain access to the British army and rugby football. These institutions are still considered the two most viable career paths for young men and, by extension, the easiest way extended families can secure economic stability. This has recently been accentuated by the success of the Fijiian rugby sevens team, whose gold medal success in the 2016 Olympic Summer Games brought the image of Fijian warriors to a global audience. For Indo-Fijians, the patriarchal smallholding became a ticket to independence early on while today, families hedge their bets on supporting boys and young men to gain a good enough education to migrate overseas. All of these forces conspire to make masculinity, its local meanings and articulations, and the way men insert themselves into global flows and negotiate the demands of late modern society, both timely and important research foci.

At the same time, it is challenging to frame such a research project. It is indeed unclear to me when the sense of what a study of masculinity in Fiji actually entailed started to emerge for me. For the first few months of my fieldwork, I worked hard to make connections between my theoretical assumptions and broader research ambitions on the one hand and the data I gathered on the ground on the other. I spent most of my time in the company of other men and quickly filled my notebooks with impressions, descriptions, stories and opinions from new friends and acquaintances. Still, I grappled with the fear that my total body of work would amount to little more than just a Geertzian thick description of the things men did and talked about on a regular basis. A key challenge was that I found it difficult to engage my interlocutors themselves in discussions that were overtly about gender identities and performances. Concepts such as masculinity and gender had very little meaning to most of them beyond the taken-for-grantedness of distinctions between men and women, boys and girls that permeated most social settings. This gender order was in many ways seen as a completely natural state of affairs, hardly worth contemplation or discussion.