THE ORIGINS OF POLITICAL ORDER

ALSO BY FRANCIS FUKUYAMA

After the Neocons: America at the Crossroads

State-Building: Governance and World Order in the Twenty-first Century

Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution

The Great Disruption: Human Nature and the Reconstitution of Social Order

Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity

The End of History and the Last Man

THE ORIGINS OF POLITICAL ORDER

From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

www.profilebooks.com

First published in the United States of America in 2011 by

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Copyright Francis Fukuyama, 2011

Maps copyright Mark Nugent

Grateful acknowledgement is made for permission to reprint the following material: Excerpts from Islam from the Prophet Muhammad to the Capture of Constantinople. I: Politics and Government, edited and translated by Bernard Lewis, copyright 1987 by Bernard Lewis. Reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press. Excerpts from Chinese Government in Ming Times: Seven Studies, edited by Charles O. Hucker and Tileman Grimm, copyright 1969 by Columbia University Press. Reprinted by permission of Columbia University Press.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays, Bungay, Suffolk

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84668 256 8

eISBN 978 1 84765 281 2

The paper this book is printed on is certified by the 1996 Forest Stewardship Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer holds FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-2061

IN MEMORY OF

Samuel Huntington

CONTENTS

PREFACE

This book has two origins. The first arose when my mentor, Samuel Huntington of Harvard University, asked me to write a foreword to a reprint edition of his 1968 classic, Political Order in Changing Societies. Huntingtons work represented one of the last efforts to write a broad study of political development and was one I assigned frequently in my own teaching. It established many key ideas in comparative politics, including a theory of political decay, the concept of authoritarian modernization, and the notion that political development was a phenomenon separate from other aspects of modernization.

As I proceeded with the foreword, it seemed to me that, illuminating as Political Order was, the book needed some serious updating. It was written only a decade or so after the start of the big wave of decolonization that swept the postWorld War II world, and many of its conclusions reflected the extreme instability of that period with all of its coups and civil wars. In the years since its publication, many momentous changes have occurred, like the economic rise of East Asia, the collapse of global communism, the acceleration of globalization, and what Huntington himself labeled the third wave of democratization that started in the 1970s. Political order had yet to be achieved in many places, but it had emerged successfully in many parts of the developing world. It seemed appropriate to go back to the themes of that book and to try to apply them to the world as it existed now.

In contemplating how Huntingtons ideas might be revised, it further struck me that there was still more fundamental work to be done in explicating the origins of political development and political decay. Political Order in Changing Societies took for granted the political world of a fairly late stage in human history, where such institutions as the state, political parties, law, military organizations, and the like all exist. It confronted the problem of developing countries trying to modernize their political systems but didnt give an account of where those systems came from in the first place in societies where they were long established. Countries are not trapped by their pasts. But in many cases, things that happened hundreds or even thousands of years ago continue to exert major influence on the nature of politics. If we are seeking to understand the functioning of contemporary institutions, it is necessary to look at their origins and the often accidental and contingent forces that brought them into being.

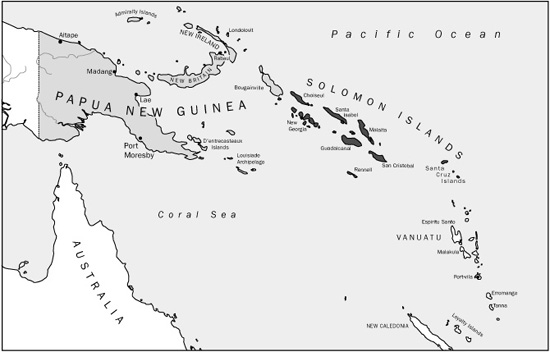

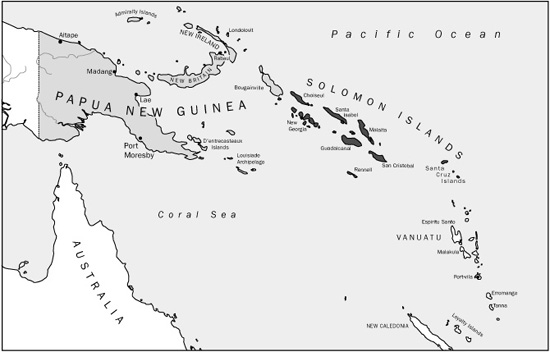

The concern over the origin of institutions dovetailed with a second preoccupation, which was the real-world problems of weak and failed states. For much of the period since September 11, 2001, I have been working on the problems of state and nation building in countries with collapsed or unstable governments; an early effort to think through this problem was a book I published in 2004 titled State-Building: Governance and World Order in the Twenty-first Century. The United States, as well as the international donor community more broadly, has invested a great deal in nation-building projects around the world, including Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Haiti, Timor-Leste, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. I myself consulted with the World Bank and the Australian aid agency AusAid in looking at the problems of state building in Melanesia, including Timor-Leste, Papua New Guinea, Indonesian Papua, and the Solomon Islands, all of which have encountered serious difficulties in trying to construct modern states.

Consider, for example, the problem of implanting modern institutions in Melanesian societies like Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. Melanesian society is organized tribally, into what anthropologists call segmentary lineages, groups of people who trace their descent to a common ancestor. Numbering anywhere from a few dozen to a few thousand kinsmen, these tribes are locally known as wantoks, a pidgin corruption of the English words one talk, or people who speak the same language. The social fragmentation that exists in Melanesia is extraordinary. Papua New Guinea hosts more than nine hundred mutually incomprehensible languages, nearly one-sixth of all of the worlds extant tongues. The Solomon Islands, with a population of only five hundred thousand, nonetheless has over seventy distinct languages. Most residents of the PNG highlands have never left the small mountain valleys in which they were born; their lives are lived within the wantok and in competition with neighboring wantoks.

Melanesia

The wantoks are led by a Big Man. No one is born a Big Man, nor can a Big Man hand that title down to his son. Rather, the position has to be earned in each generation. It falls not necessarily to those who are physically dominant but to those who have earned the communitys trust, usually on the basis of ability to distribute pigs, shell money, and other resources to members of the tribe. In traditional Melanesian society, the Big Man must constantly be looking over his shoulder, because a competitor for authority may be coming up behind him. Without resources to distribute, he loses his status as leader.

Next page