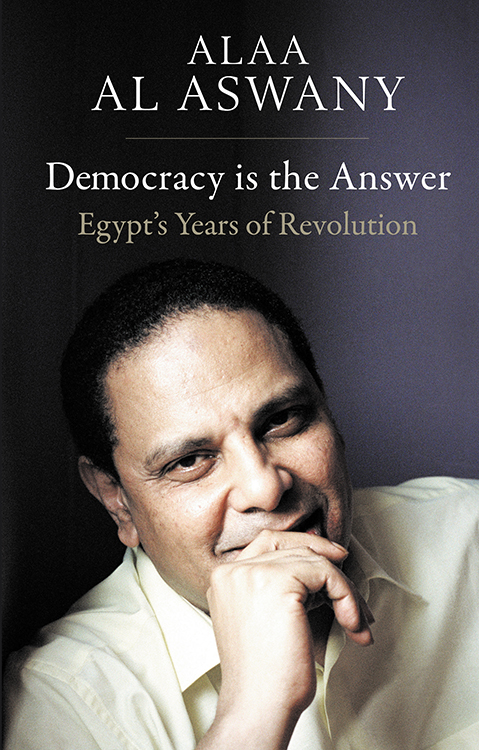

ALAA AL ASWANY

Democracy is the Answer

Egypts Years of Revolution

Translated by Russell Harris, Aran Byrne and Paul Naylor

Contents

2011

2012

2013

2014

Introduction

I woke up on 25 January 2011 like it was any other day. I got out of bed and wrote until midday. I had heard about the demonstration that had been organised, but I was not optimistic that anything would come of it. I had taken part in many demonstrations against Hosni Mubarak before and they had all been more or less the same: a few hundred demonstrators would be encircled by thousands of police officers who would close in on the demonstrators, beat them and make arrests.

When I did go down to Tahrir Square in the afternoon I was met with an astonishing scene: Egypt had awoken from its sleep. Hundreds of thousands of Egyptians had poured out onto the streets, all chanting one slogan: The people want the fall of the regime! For the next 18 days I lived in Tahrir Square and these were, without doubt, the most wonderful days of my life. I learned a lot from the revolution and began to truly understand the meaning of the people. There were two million of us living in Tahrir Square, and the number would double in the evenings. We all felt as though we were members of one family: we ate and drank together, we chanted slogans and sang songs together, and we also faced the deadly bullets shot by snipers together. We didnt show fear and we didnt retreat. We carried those who fell, and with each adversity we grew even more determined to bring down Mubarak no matter what the cost.

Ill never forget the moment when Mubaraks resignation was announced on television. Millions of Egyptians embraced each other and wept, overwhelmed by a joy they had never before experienced. The next day, millions of young people came out and swept away the rubbish from all the streets of Egypt; it was a sign that their country had been returned to them and that from now on, they would strive to keep it clean. But what went wrong after this?

Historians will face a difficult job uncovering the underlying causes behind the events that followed the fall of Mubarak. Contrary to their expectations, Egyptians found themselves facing deteriorating conditions conditions that were worse than anything that they had suffered during the era of Mubarak. The prisons were opened up and tens of thousands of criminals were let out onto the streets to cause havoc and terrorise ordinary Egyptians. Law and order broke down and the living conditions of most Egyptian citizens deteriorated drastically. Then the Muslim Brothers took over: first, they gained control of the parliament by buying the votes of poor people, and then their candidate, Mohamed Morsi, took the presidency through dubious elections. On 22 November 2012, Morsi gave his presidential decrees immunity from legal challenge, thereby placing himself above the constitution and the rule of law. When this happened, millions of Egyptians took to the streets to demand that Morsi step down, insofar as he was now acting more like a despotic Turkish sultan than the president of a democratic country. In the absence of a parliament that could have held a vote of no confidence against Morsi and, thereby, forced him to resign, the Tamorod campaign was started. Its aim was to collect signatures in order to show that the people had withdrawn their support for Morsis presidency. I took part in this campaign myself, collecting the signatures of passersby in the streets of Alexandria.

In the end, 22 million people signed the petition and, on 30 June 2013, more than 30 million Egyptians took to the streets to demand that Morsi step down and that early presidential elections be held. In opposition to this, tens of thousands of Islamists came together for sit-ins in Rabaa Al-Adawiya Square and Al-Nahda Square. Their leaders incited them to fight the enemies of Islam, that is to say, those Egyptians who rejected Gods rule, as represented by Mohamed Morsi. Egypt was on the verge of civil war until the army intervened to remove Morsi from power. It was at this point that a new star arose: General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, the former head of Egypts armed forces. The huge popularity he gained for his role in Morsis ouster later enabled him to take the presidency of Egypt with ease.

In the pages of this book you will find these successive events dealt with in more detail. In this sense, the book is a record of Egypts experiences since the outbreak of the revolution. The articles collected here were originally weekly newspaper columns that were published in the Egyptian newspaper Al-Masry Al-Youm and the Lebanese newspaper As-Safir, over the course of three years. The articles were later translated and published around the world by various international newspapers and journals. For that reason, I was always conscious that I was writing for both an Egyptian audience and a wider international one.

I should point out that I am neither a historian nor a political analyst. I am a novelist, and as such I used fictional writing in my articles to portray how Egyptians felt during the often troubling and painful events they have lived through. I firmly believe that, as a writer, I had a duty to write these articles to convey the political message of those who took part in the revolution. In my mind, writers should not keep themselves locked away behind closed doors; they should live amongst the people, listen to their stories and try to give them a voice. In this sense, writing should be used to promote and defend human values. It represents an effective means of communication with the wider society. I tried to use what was happening in Egypt to convey a human message to my readership because I believe that when you write about human experiences, everyone can understand and identify.

As a writer, I never saw it as my role to impose my own views on those who read my work. Rather, I saw it as my responsibility to go out and listen to the people in order to better understand the situations they faced and then find a way to best express their thoughts, feelings and aspirations. I do not see myself as being separate from the people; however, from the beginning of the revolution, I understood that, as a novelist, I had a particular role to play in it, that I had a duty to defend the people and to defend human rights through my writing, as well as by directly participating in the events of the revolution. There are, of course, risks associated with both forms of protest; I have been attacked in Egypt, as well as abroad, because of things I have said and written. Many of my friends and fellow Egyptians, however, have paid a much greater price for protesting; they have been arrested, beaten, tortured, blinded by rubber bullets and killed in the streets. As an Egyptian, and as a writer, you have to be prepared for anything; the only other option is to surrender to tyranny.

At the time of writing, the mood in Egypt has changed and popular support for the revolution has declined significantly. Egyptians had high expectations after the fall of Mubarak, but they have suffered a lot over the last three years and, for many of them, life seems more difficult now. The military council and the Muslim Brotherhood bear political responsibility for the difficult economic climate and deteriorating living conditions in Egypt because they were in power during this period. The forces of counter-revolution sought to exhaust the Egyptian people by creating artificial crises, for which they then tried to blame the revolution. At the same time, they deliberately set out to smear the revolutionaries and crush them by carrying out a series of massacres. Under Mubarak, licenses for private-owned television stations were reserved for rich businessmen with close connections to the Mubarak regime. These channels continue to censor dissident voices and to tarnish the reputation of the revolutionary forces. They accuse them of treason and of being foreign agents, intent on toppling the state. Television is by far the most important medium in Egypt and these accusations have had a considerable impact on public opinion and attitudes towards the revolution. On top of this, in recent months there have been a number of terrorist attacks in Egypt that have forced it to declare a state of emergency. These attacks constitute a serious threat to the Egyptian state, and many believe that it is unhelpful to talk about the need for freedom of expression and democracy at the present time. The Egyptian people have been shaken by these attacks and are reluctant to say anything against the state institutions, including the army, the police and the judiciary, in case it undermines security. In my opinion, however, the best way to serve those in power is to criticise them, not to agree with everything that they do for the sake of showing a united front. It is our duty as citizens of Egypt to enter a dialogue with those in power and to hold them to account for their actions, especially if the Egyptian people suffer as a result of their decisions. This was one of the key demands of the Egyptian revolution.