First published in 2019 by

HAUS PUBLISHING LTD

4 cinnamon row

London SW11 3TW

www.hauspublishing.com

This first paperback edition published in 2021

Copyright 2019, 2021, Alaa Al Aswany

English translation 2019, 2021 Russell Harris

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-913368-04-3

eISBN: 978-1-912208-60-9

Typeset in Garamond by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in the United Kingdom by TJ Books, Padstow

All rights reserved.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders and obtain permission to reproduce the material quoted in this book. The publisher would be pleased to rectify any omissions in subsequent printings of the book should they be drawn to our attention.

Authors note

I first made the acquaintance of Barbara schwepcke some years ago when she was introduced to me by another dear friend, the now late Mark Linz, Director of the American University in Cairo Press. Barbara was Marks partner both in life and professionally, and we three used to meet quite often in Cairo, London and Frankfurt. We would spend long hours discussing what was happening in the world, particularly in Egypt, a country that both Mark and Barbara loved. Over time, I discovered that Barbara was driven by a personal commitment to defend freedom everywhere and that she used book publishing as a weapon against ignorance, authoritarianism and indeed against anything that deprived people of their human rights. When the Egyptian revolution broke out in 2011, Barbara gave it her wholehearted support. She travelled to Cairo and went to Tahrir Square to listen to what people were saying. She spoke to everyone she knew about the revolution and its inherent risks. She was as supportive of the revolution as any Egyptian revolutionary.

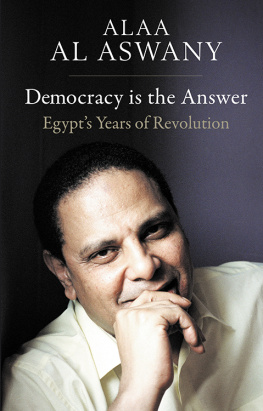

Three years later, when General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi took power, my work was blacklisted in Egypt. Around the same time, I suggested to Barbara that she might publish all my articles about the revolution in book form. She held the view that my novels had already been translated into various languages and that my fiction was well known, but that my articles also needed to be made accessible to a non-Arab readership. She told me that no one could prevent me from publishing my thoughts and that the best response to my being blacklisted would be to publish a collection of my articles. Barbara decided that the title of the book should be Democracy is the Answer, which was the refrain with which I finished all my articles. The book was published in London to positive acclaim from the English readership.

Some months later, I came up with another suggestion for Barbara: that she should hold a series of discussions with me about the phenomenon of dictatorship in the twentieth century, which could then be published as a book. She was enthusiastic about the idea, and we started to have regular conversations, recorded by her two assistants. Barbara a woman of great culture had an astonishing talent in directing the debate. Our conversation ended up touching on other related topics of significance, and I started to look for signs of dictatorship in humanity in general. What was the difference between a youth who has grown up in China or Egypt and a youth of the same educational level in Britain or America? How do traces of dictatorial attitudes find their way into the behaviour of the everyday citizen?

I will always remember the evening I was sitting in my room in the Gore Hotel in London. I was doing some reading before the next days debating session, when a new thought came to me. The next morning, I told Barbara that the subject of our discussions was too weighty and that a debate might not be the best way to present it to the public. I said that I wanted to write about the subject as a series of articles instead. She agreed on the spot and suggested, there and then, that I should write my study of dictatorship in the form of a medical report titled The Dictatorship Syndrome.

My dear friend and literary agent Charles Buchan found the concept exciting and had a contract speedily drawn up. We all agreed that Russell Harris, an accomplished translator, should be asked to transpose the text into English.

I started work on the book immediately and finished around half of it in Cairo. My relationship with the Egyptian regime had by then deteriorated to the point where my presence in my own country represented a threat both to me and to members of my family, so I copied the half-finished book onto a USB drive and hid it between the toothpaste and shaving cream in my washbag as I left the country. Whenever I enter or exit Egypt, the authorities pull me to one side and make me wait as they go through my suitcase twice before letting me go. Had they found material for a book, they would have confiscated it and had it examined by a committee of officers and I would then have, most probably, been hauled off to court and seen levelled against me yet another charge of slandering the institutions of state.

This kind of censorship is just one of the many reasons why I believe that we, now more than at any other time, need to understand the dictatorship syndrome. The victims of dictatorship worldwide outnumber those struck down by any disease.

Once in New York, I resumed work. The chapters were translated one by one and sent on to Charles who made most valuable comments on the text, as did the publisher at Haus, Harry Hall.

Dear reader, you now have my book in your hands. I hope you like it.

1

The syndrome

I was a boy of ten when the 1967 war between Egypt and Israel broke out. Gamal Abdel Nasser (19181970) was in sole charge of Egypt and took oppressive and violent measures against any and every person who put up opposition to him. Notwithstanding his authoritarianism, Nasser had adopted revolutionary socialist policies,

At that time, the Egyptian people were buffered from what was going on in the world because the Nasserite propaganda machine shaped public opinion in Egypt in accordance with instructions from the security apparatus. Foreign radio stations, such as the BBC and the Voice of America, were subjected to continuous scrambling, and the authorities warned citizens against listening to them as they broadcast lies and anti-revolutionary propaganda.as a world leader responsible for standing up to colonialism globally, and in line with his conception of Arab nationalism he had declared a union between Egypt and Syria in 1958. However, the overbearing behaviour of the Egyptian top brass caused Syria to revolt and secede from the union in September 1961. Then, in 1962, Nasser sent the Egyptian army to Yemen to support the Republicans against the Royalists and became bogged down in an absurd war that led to the deaths of thousands of soldiers and the exhaustion of the most efficient fighting units of the army. This whole debacle was kept hidden from the public in Egypt, and the Nasserite information machine still managed to convince us that our national army was the greatest fighting force in the Middle East and that one day it would crush the Israeli army within a few short hours and throw Israel into the sea as it liberated Palestine once and for all.