Preface

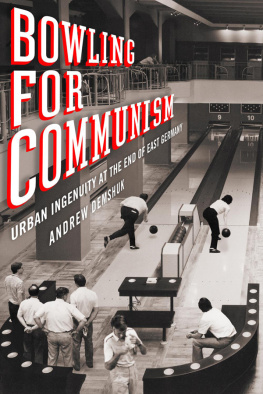

Along the main ring road across from Leipzigs monumental new city hall, an octagonal sandstone faade with smashed windowpanes and a coat of graffiti festers behind weedy trees that wave in the wind. In a bowl-shaped depression of broken glass and pavement several meters back from this wreck, a corroded claw arises to clasp a red stone orb. Behind locked gates that face traffic on the ring road, a defunct neon sign gives a clue about this moldering enigma: in a mix of English and German, faded yellow cursive letters reveal that this had been the Bowlingtreff. Completed in 1987, this lofty little hall with its vast subterranean bowling lanes, cafes, bars, and hip accoutrements opened its doors to waves of eager citizens: a gleaming, popular magnet alone in a sea of rotting, collapsing historic neighborhoods that suffocated under a constant brown haze from the moonscape of strip mines and lignite power plants to the immediate south. Outfitted with Western technology and cutting-edge postmodern flourishes, this wonder arose thanks to unorthodox, even illegal, daring from local officials and architects, not to mention thousands of hours of free labor from Leipzig citizens. Ten years later, as the city awoke from its communist-era decay to miraculously transfigure into one of Germanys most lively historic centers, the Bowlingtreff closed because of capitalist mismanagement and steadily metamorphosed into an eyesore akin to what the rest of the city had been back in 1987. The story of this unequaled late-communist, early-postmodern edifice was forgotten. Only its forlorn neon sign and bowling-ball-shaped fountain testify to its onetime identity. Like most passersby, I was dumbfounded when I first stumbled across what was left of Leipzigs Bowlingtreff. Little did I suspect that this architectural riddle bore within it a host of human stories and contradictions that could unlock the inner workings of East Germanys second-largest city on the eve of the 1989 Peaceful Revolution, in which it played a principal role.

This book first came into being amid a personal quest to understand the oddity that is Leipzigs Bowlingtreff. Through previous research, I had explored how waves of public protest against heedless regime-led demolitions had peaked with the destruction of Leipzigs intact Gothic University Church in 1968; from that point onward, ceaseless communist party (SED) propaganda of work with us (mach mit) had lost its dwindling sparkle, and urban planning objectives had met with disinterest, disbelief, and derision as damaging, hideous, and downright impossible anyway, given an ever more chronic shortage economy. Yet for all this profound pessimism, in 1987, 6,675 young Leipzigers devoted 40,050 hours of volunteer labor to ensure that this recreational center arose in only fourteen months on a shady budgetand without the knowledge of central authorities in Berlin until the very end. How did local authorities green-light construction of a major showpiece without permission from Berlin? How could it be that so many people had chosen to work with local authorities by devoting so many hours to such an optimistic project on the eve of a revolution when they marched against the regime?

As I delved deeper into archived public letters, architectural plans and correspondence, protest paraphernalia, and discussions with eyewitnesses, I came to realize that the Bowlingtreff in fact typified a larger, ultimately intractable quandary in state-citizen relations as they had evolved by the end of East Germany (the DDR). Though largely neglected in scholarship that investigates the bases of the 1989 revolution that brought down communist rule, runaway urban decay and the usually quixotic struggle to overcome it not only set the stage for the popular upheaval in which Leipzig helped to change the course of world history; they represented a conjunction of other factors already familiar to scholars. By using Leipzigthe capital of the Peaceful Revolutionas a case study, and by homing in on responses to urban blight by both local leaders and public actors, I found intimate details about how economic problems, the housing shortage, ecological disasters, political corruption, and loss of belief (even by party members) laid the groundwork for revolution when external factors, such as perestroika and Mikhail Gorbachevs pacifism, ensured that it would not end like East Germanys 1953, Hungarys 1956, or Czechoslovakias 1968. For both local leaders and residents, their dismal surroundings eloquently portrayed how, to attain any positive outcome, one had to work around the system. Economically, functionally, and morally bankrupt, the centralized regime was proven to be an obstruction at best, parasitic at worst, and utterly counterproductive for attaining positive outcomes. The object lesson was plain, if often unstated: Why should locals or even leaders sustain a system that had condemned the historic city to destruction? For years, they had learned to work around it; were they not better off without it?

This books evidence upends the dual stereotype of both official incompetence and public passivity in the late DDR by documenting pervasive local initiative I call urban ingenuity. On the one hand, it redeems the intentions of a new generation of political and planning elites who expended considerable creative energy and innovation to try to combat urban blight and build a humane city. In their multipronged campaign to unify historical architecture with modern construction methods, they proved that in principle East German professionals were taking full part in the Western shift toward historic preservation after decades of rampant modernist destruction. Conscious that the previous modernist drive for utopia had instead wrought dystopia, they pushed a new vision that increasingly split off from contemporary limitations in material and labor and ultimately broke from reality itselfevincing not only rebellion from Politburo mandates but also disconnect from urgent public concerns. They wanted to revise utopia; political and economic realities made them produce serialized blocks that perpetuated the decimation of urban history and character. They wanted to win back public affections with a palatial bowling alley, wherein Leipzigers would sense they were bowling for communism, enjoying recreational fun imbued with gratitude for SED beneficence toward popular desires. But Leipzigers embraced the Bowlingtreff as an island of the West that only whetted their appetites for the better world so obviously lacking in the bleak cityscape outside.

On the other hand, urban ingenuity illustrates how disaffected local homeowners, preservationists, church communities, and young people sought to satisfy their needs and interests within the bounds of late communism. Having long since given up on taking part in shaping the overall appearance of their dear city, Leipzigers were nonetheless eager to take advantage of any opportunity to make something out of their rapidly decaying surroundings when the authorities gave them the chance to work with themoften necessarily working around existing strictures in the system. Notwithstanding platitudes from local officials once the Bowlingtreff opened, public participation in assembling the structure implied neither belief that they were building real existing socialism nor tacit support for local programs. Even employees at the sparkling new Bowlingtreff were so dismayed by years of accumulated disappointments, endemic corruption, and catastrophic shortages that, rather than stay to relish their East German recreational palace, some of them risked escape to West Germany. And two years after scores of young people had helped to build the Bowlingtreff, they marched against the very leaders who had made it possible. They knew this lone monument could not save their city. Numerous interviews in a late 1989 film had inspired its provocative title: