Copyright 2015 by The University of Arkansas Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-55728-759-5

e-ISBN: 978-1-61075-564-1

19 18 17 16 15 5 4 3 2 1

Designed by Ellen Beeler

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015931484

Preface

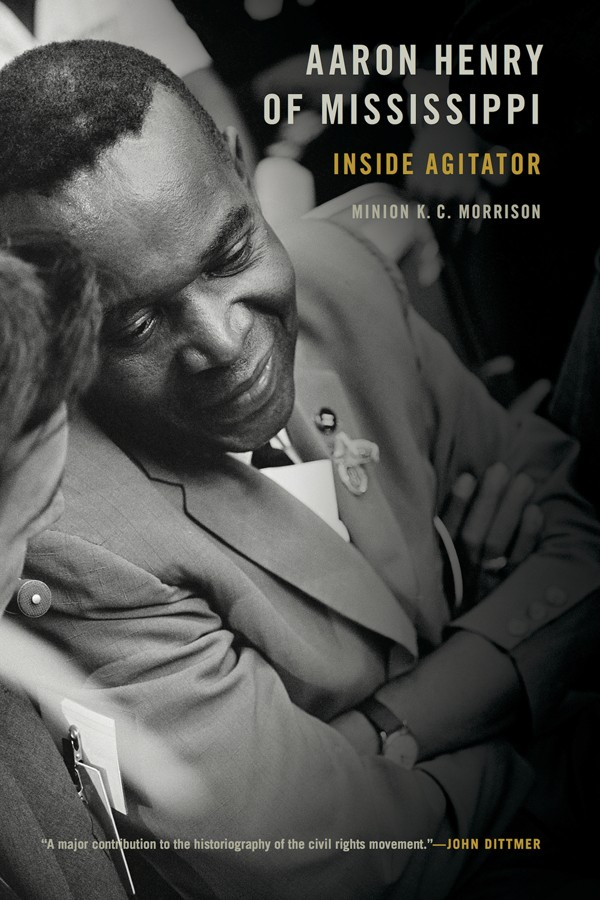

I hardly knew when this project came up in a casual conversation with my good friend, the writer and poet Jerry Ward, that it would occupy me for the next fifteen years. The subject arose as we discussed the Mississippi civil rights movement and the necessity of documenting and assessing the period. Ward noted that Aaron Henrys life cried out for biographical treatment. At the time I was leaving a senior-level administrative position at the University of Missouri to return to research, and pondering the next project. I assumed I would again go off to West Africa to pursue the newly reemergent political parties, a project I did subsequently pursue (and finished before the Henry biography!).

Yet I opted to undertake a biography on Henry, never imagining the time investment and what I would have to learn about the historians craft to pull it off. Henry intrigued me for a variety of reasons. I had been active at the tail end of the civil rights movement in Mississippi and worked in a number of Delta towns. It struck me that an exploration of Henrys long life of activism would provide an opportunity to make a professional assessment of events that had moved me to political action as I left high school in the mid-1960s. Moreover, there was a natural attraction to the subject because I have produced some scholarship on post-movement electoral politics in Mississippi, in particular black mayors in the 1970s. At the same time, because Henry spanned the movement of the 1950s and 1960s, and the succeeding electoral politics phase, an extended study of his work seemed to be an opportunity to interrogate the degree to which an activist could move into electoral politics and maintain integrity to the vision of social movement. Thus inspired, I took up the proposition that Ward offered, and this product is the result.

The pursuit of the project became a great deal easier when the first proposal I wrote attracted funding. The Research Board of the University of Missouri System provided an award allowing me to begin a preliminary investigation of the substantial body of Aaron Henrys personal papers. Only then did I begin to understand something of the scope of this undertaking. Henry preserved a treasure trove of material (notwithstanding a substantial loss of early documents in a fire bombing of his drugstore). Happily, much of this material had already been organized and catalogued by the staff at the Coleman Library of Tougaloo College, which houses a substantial additional civil rights collection, also relevant to Henrys life. This Lillian Benbow collection is now stored at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH) and largely curated by Clarence Hunter. The trove made it easy to become immersed in the subject as I undertook even a mere perusal of the collection. That proved just the tip of the iceberg. Henry was substantively engaged with many other networks and organizations, leading to major papers and documentation about him in research repositories all over the country. Therefore, I found myself chasing after these materials wherever I found important leads.

In the process of discovery, librarians and archivists in the Tougaloo Coleman Library, especially Clarence Hunter and Alma Fischer, ably assisted me. Ann Harper exercised due diligence in keeping up with graduate students from the University of Missouri (Kevin Anderson and Richard Middleton IV), as well as a number of Tougaloo undergraduate students who helped me explore these archives. The MDAH and its tremendous staff assisted me in developing a film on Aaron Henrys life from its filmstrips collection and in locating and processing documentation. The Mitchell Library at Mississippi State University and its special collections staff (Mattie Abraham, in particular) were especially helpful in getting me access to its civil rights collection and to acquire permission to see the Patricia Derian Papers (then not publicly available). Similarly, the Oral History Collection at Mississippi Southern University made a substantial amount of material available during a personal visit and via its online collection. Archivists and librarians at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin; the Wayne State University Walter Reuther LibraryAaron Henry Papers; the University of North CarolinaChapel Hill Wilson Collection, where the Allard Lowenstein Papers are housed; the Oral History Collection at Columbia University; and the Library of Congress all provided important documentation.

I am grateful to many sources in Clarksdale, Mississippi, including members of the Henry family who submitted to interviews. In addition, I conducted many interviews with activists, business partners, friends, and politicians who worked with Henry in the movement, the Democratic Party, and the Mississippi legislature. I am lucky that many of his confreres in the movement remained alive and proved willing to share their recollections about Henry.

A project that extends as long as this one obviously has many graduate students, secretaries and other clerical assistants, and family members whose contributions must be noted. The Department of Political Science at the University of Missouri was supportive during my tenure there. I was afforded leaves of absence and good support from a number of graduate students. Among them were Leah Graham, Dursun Peksen, and Rollin Tusalem. Similarly, Sarah Turner of the clerical staff did an excellent job transcribing interviews. I enjoyed excellent support from the Department of Political Science and Public Administration and the African American Studies Program at Mississippi State University, which also provided assistance from several graduate and undergraduate students (among them Hannah Carlen, Kaleb Gipson, and DAndrea Latham). The clerical staff of Quintara Miller and Kamicca Brown also provided welcome technical support. My wife and daughter, Johnetta and Iyabo, maintained high, steady interest and support throughout a project that must have seemed unending.

INTRODUCTION

The racial system in Mississippi in the 1940s made any project for social change a tall order, unlikely to be carried off by a single individual. The organized repression and the deeply ingrained rituals inevitably required a variety of forces to overturn this system. Even so, among the multiple leaders that eventually emerged, Aaron Henry played an outsized role that makes telling his personal story so compelling. His is a story when viewed from beginning to end that reveals a core vision for the racial transformation of Mississippi society and politics. At the outset he possessed a distinctive set of personal skills that allowed him to help compose and sustain a confederation of early movement activists and other supporters. Following a social movement of notable achievements, he then helped acquire and largely oversaw distribution of a vast array of resources that overwhelmed the day-to-day, formal, and customary aspects of the racial system in Mississippi (and beyond). This work is the story of his singular importance in transforming arguably the most intractable racial system in the country.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984.