2017 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

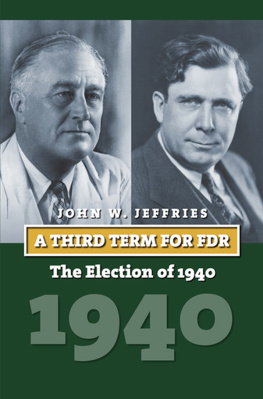

Names: Jeffries, John W., 1942 author. Title: A third term for FDR : the election of 1940 / John W. Jeffries.

Description: Lawrence : University Press of Kansas, 2017. | Series: American presidential elections | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016055772

ISBN 9780700624027 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 9780700624034 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: PresidentsUnited StatesElection1940. | Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano), 18821945. | Willkie, Wendell L. (Wendell Lewis), 18921944. | United StatesPolitics and government19331945.

Classification: LCC E811 .J44 2017 | DDC 973.917092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016055772.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication is recycled and contains 30 percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials z39.48-1992.

EDITORS FOREWORD

To most of the fifty-five delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, the absence of any limit on the number of terms a president could serve was an important feature of the new plan of government they were creating. Unrestricted eligibility for reelection would allow the nation to keep a good executive in office and give the president what Pennsylvania delegate Gouverneur Morris called the great motive to good behavior, the hope of being rewarded with a re-appointment. During the ratification process, Alexander Hamilton of New York argued in Federalist No. 72 that even a president whose behavior was governed by personal motives such as ambition, avarice, or the love of fame would do a good job in order to hold on to the office that could fulfill those desires. More ominously, Morris warned: Shut the Civil road to Glory & he may be compelled to seek it by the sword.

So where did the ideasoon reified into custom and, in 1951, into the Twenty-Second Amendment to the Constitutionthat no president should serve more than two terms come from?

Not, as John W. Jeffries points out in A Third Term for FDR from the first president, George Washington. Washington intended no precedent when he stepped down after his second term. Instead, he retired for reasons that were particular to his and the nations circumstances. He longed, Washington wrote, for the shade of retirement. And he thought it was important for the country to see that the Constitution could work even if he was no longer president.

Thomas Jefferson had a different viewin fact, had it from the moment he first read the proposed Constitution while serving as the American minister to the French government in Paris. Although Jefferson generally admired both the delegates to the convention and the plan of government they produced, he objected strongly to the absence of a term limit on the president. Their President seems like a bad edition of a Polish king, Jefferson lamented in a letter to John Adams, then serving as minister in London, on November 13, 1787. He may be reelected from 4. years to 4. years for life.... Once in office, and possessing the military force of the union, without either the aid or check of a council, he would not be easily dethroned, even if the people could be induced to withdraw their votes from him. I wish that at the end of the 4. years they had made him for ever ineligible a second time.

As president, Jefferson managed to temper his objections to presidential reeligibility enough to seek and win a second term in 1804. But his expediency on the term-limit issue extended only so far. In 1806 and 1807, six state legislatures petitioned Jefferson to stand for a third term. On December 10, 1807, in a letter to the legislature of Vermont, he replied that no president should serve in office longer than eight years. Echoing in a slightly modified key his two-decade-old statement to Adams, Jefferson wrote, If some termination to the services of the Chief Magistrate be not fixed by the Constitution, or supplied by practice, his office, nominally four years, will in fact become for life, and history shows how easily that degenerates into an inheritance. To strengthen his argument for a two-term tradition, Jefferson even invoked the sound precedent set by an illustrious predecessor, falsely elevating Washingtons personal decision into an unwritten rule that all of his successors were expected to follow.

Nonetheless, the rule took root. No president even was nominated for a third term until 1940, when Franklin D. Roosevelt ran. Jeffries thoroughly explores FDRs motives and the controversy that his third-term candidacy triggered both within the Democratic Party and in the general election campaign against Republican Wendell Willkie. Surviving the GOPs Out Stealing Third cry with supporters Safe on Third reply, Roosevelt won a third landslide victory, although by a smaller margin than in 1932 and 1936. In a time of domestic and, especially, international uncertainty, Jeffries shows, the voters chose not to change horses in midstream.

Far from shattering the two-term tradition, Roosevelts successful reelection campaigns in 1940 and then in 1944 triggered such a strong conservative backlash that the Twenty-Second Amendment was enacted by Congress in 1947 and ratified by the states in 1951, forbidding third terms. Congressional Republicans drove the process, although as Jef-fries points out, Some were less happy about the amendment in 1960, when it appeared that Dwight D. Eisenhower could have been elected to a third term had he chosen to run.

Michael Nelson

John McCardell

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have depended in many ways on the help and efforts of others in writing this book, and I have incurred debts that I cannot repay but can at least gratefully acknowledge. I thank Fred M. Woodward, former director of the University Press of Kansas, and the series editors, Michael Nelson and John McCardell, for inviting me to write this book. At the Press, Director Charles Myers has shepherded the process, Sara Henderson White has readily given important assistance and advice, and Larisa Martin and the production staff have expertly seen the book through to publication. The staffs of the Albin O. Kuhn Library and Gallery at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, and of the Lilly Library at Indiana University all provided essential help in my research as well as pleasant and productive places to work. At the Roosevelt Library, I must especially thank Matt Hanson for his assistance.